America’s History: Printed Page 231

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 208

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 203

The Jefferson Presidency

From 1801 to 1825, three Republicans from Virginia — Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe — each served two terms as president. Supported by farmers in the South and West and strong Republican majorities in Congress, this “Virginia Dynasty” completed what Jefferson had called the Revolution of 1800. It reversed many Federalist policies and actively supported westward expansion.

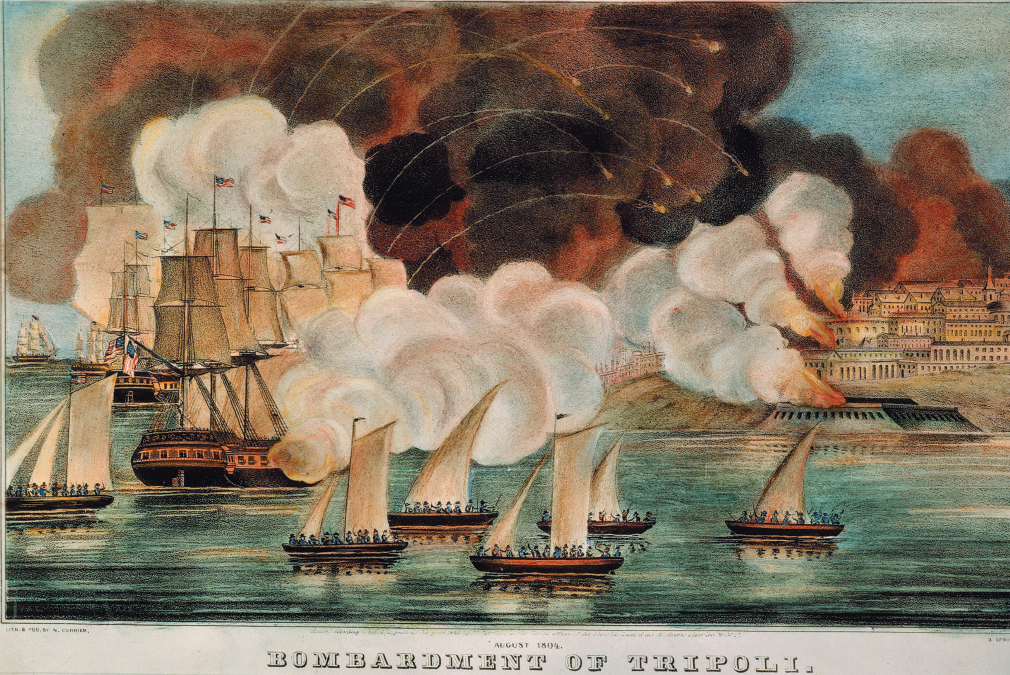

When Jefferson took office in 1801, he inherited an old international conflict. Beginning in the 1780s, the Barbary States of North Africa had raided merchant ships in the Mediterranean, and like many European nations, the United States had paid an annual bribe — massive in relation to the size of the federal budget — to protect its vessels. Initially Jefferson refused to pay this “tribute” and ordered the U.S. Navy to attack the pirates’ home ports. After four years of intermittent fighting, in which the United States bombarded Tripoli and captured the city of Derna, the Jefferson administration cut its costs. It signed a peace treaty that included a ransom for returned prisoners, and Algerian ships were soon taking American sailors hostage again.

At home, Jefferson inherited a national judiciary filled with Federalist appointees, including the formidable John Marshall of Virginia, the new chief justice of the Supreme Court. To add more Federalist judges, the outgoing Federalist Congress had passed the Judiciary Act of 1801. The act created sixteen new judgeships and various other positions, which President Adams filled at the last moment with “midnight appointees.” The Federalists “have retired into the judiciary as a stronghold,” Jefferson complained, “and from that battery all the works of Republicanism are to be beaten down and destroyed.”

Jefferson’s fears were soon realized. When Republican legislatures in Kentucky and Virginia repudiated the Alien and Sedition Acts as unconstitutional, Marshall declared that only the Supreme Court held the power of constitutional review. The Court claimed this authority for itself when James Madison, the new secretary of state, refused to deliver the commission of William Marbury, one of Adams’s midnight appointees. In Marbury v. Madison (1803), Marshall asserted that Marbury had the right to the appointment but that the Court did not have the constitutional power to enforce it. In defining the Court’s powers, Marshall voided a section of the Judiciary Act of 1789, in effect asserting the Court’s authority to review congressional legislation and interpret the Constitution. “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is,” the chief justice declared, directly challenging the Republican view that the state legislatures had that power.

Ignoring this setback, Jefferson and the Republicans reversed other Federalist policies. When the Alien and Sedition Acts expired in 1801, Congress branded them unconstitutional and refused to extend them. It also amended the Naturalization Act, restoring the original waiting period of five years for resident aliens to become citizens. Charging the Federalists with grossly expanding the national government’s size and power, Jefferson had the Republican Congress shrink it. He abolished all internal taxes, including the excise tax that had sparked the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794. To quiet Republican fears of a military coup, Jefferson reduced the size of the permanent army. He also secured repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801, ousting forty of Adams’s midnight appointees. Still, Jefferson retained competent Federalist officeholders, removing only 69 of 433 properly appointed Federalists during his eight years as president.

Jefferson likewise governed tactfully in fiscal affairs. He tolerated the economically important Bank of the United States, which he had once condemned as unconstitutional. But he chose as his secretary of the treasury Albert Gallatin, a fiscal conservative who believed that the national debt was “an evil of the first magnitude.” By limiting expenditures and using customs revenue to redeem government bonds, Gallatin reduced the debt from $83 million in 1801 to $45 million in 1812. With Jefferson and Gallatin at the helm, the nation’s fiscal affairs were no longer run in the interests of northeastern creditors and merchants.