America’s History: Printed Page 216

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 193

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 190

Hamilton’s Financial Program

George Washington’s most important decision was choosing Alexander Hamilton as secretary of the treasury. An ambitious self-made man of great intelligence, Hamilton married into the Schuyler family, influential Hudson River Valley landowners, and was a prominent lawyer in New York City. At the Philadelphia convention, he condemned the “democratic spirit” and called for an authoritarian government and a president with near-monarchical powers.

As treasury secretary, Hamilton devised bold policies to enhance national authority and to assist financiers and merchants. He outlined his plans in three pathbreaking reports to Congress: on public credit (January 1790), on a national bank (December 1790), and on manufactures (December 1791). These reports outlined a coherent program of national mercantilism — government-assisted economic development.

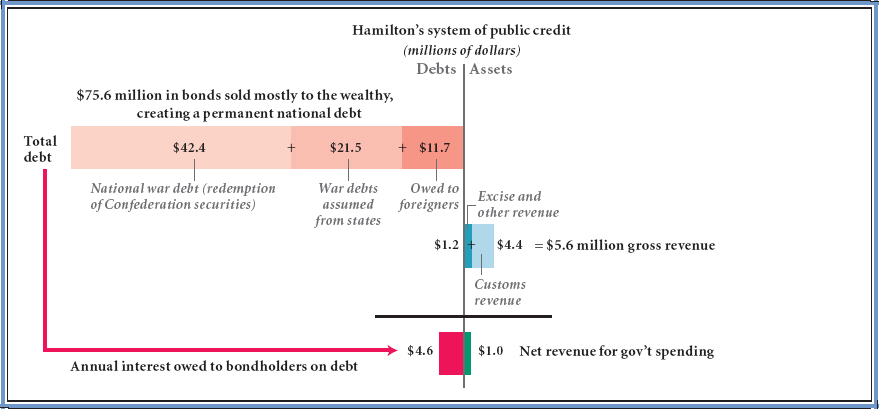

Public Credit: Redemption and Assumption The financial and social implications of Hamilton’s “Report on the Public Credit” made it instantly controversial. Hamilton asked Congress to redeem at face value the $55 million in Confederation securities held by foreign and domestic investors (Figure 7.1). His reasons were simple: As an underdeveloped nation, the United States needed good credit to secure loans from Dutch and British financiers. However, Hamilton’s redemption plan would give enormous profits to speculators, who had bought up depreciated securities. For example, the Massachusetts firm of Burrell & Burrell had paid $600 for Confederation notes with a face value of $2,500; it stood to reap a profit of $1,900. Such windfall gains offended a majority of Americans, who condemned the speculative practices of capitalist financiers. Equally controversial was Hamilton’s proposal to pay the Burrells and other note holders with new interest-bearing securities, thereby creating a permanent national debt.

Patrick Henry condemned this plan “to erect, and concentrate, and perpetuate a large monied interest” and warned that it would prove “fatal to the existence of American liberty.” James Madison demanded that Congress recompense those who originally owned Confederation securities: the thousands of shopkeepers, farmers, and soldiers who had bought or accepted them during the dark days of the war. However, it would have been difficult to trace the original owners; moreover, nearly half the members of the House of Representatives owned Confederation securities and would profit personally from Hamilton’s plan. Melding practicality with self-interest, the House rejected Madison’s suggestion.

Hamilton then proposed that the national government further enhance public credit by assuming the war debts of the states. This assumption plan, costing $22 million, also favored well-to-do creditors such as Abigail Adams, who had bought depreciated Massachusetts government bonds with a face value of $2,400 for only a few hundred dollars and would reap a windfall profit. Still, Adams was a long-term investor, not a speculator like Assistant Secretary of the Treasury William Duer. Knowing Hamilton’s intentions in advance, Duer and his associates secretly bought up $4.6 million of the war bonds of southern states at bargain rates. Congressional critics condemned Duer’s speculation. They also pointed out that some states had already paid off their war debts; in response, Hamilton promised to reimburse those states. To win the votes of congressmen from Virginia and Maryland, the treasury chief arranged another deal: he agreed that the permanent national capital would be built along the Potomac River, where suspicious southerners could easily watch its operations. Such astute bargaining gave Hamilton the votes he needed to enact his redemption and assumption plans.

Creating a National BankIn December 1790, Hamilton asked Congress to charter the Bank of the United States, which would be jointly owned by private stockholders and the national government. Hamilton argued that the bank would provide stability to the specie-starved American economy by making loans to merchants, handling government funds, and issuing bills of credit — much as the Bank of England had done in Great Britain. These potential benefits persuaded Congress to grant Hamilton’s bank a twenty-year charter and to send the legislation to the president for his approval.

At this critical juncture, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson joined with James Madison to oppose Hamilton’s financial initiatives. Jefferson charged that Hamilton’s national bank was unconstitutional. “The incorporation of a Bank,” Jefferson told President Washington, was not a power expressly “delegated to the United States by the Constitution.” Jefferson’s argument rested on a strict interpretation of the Constitution. Hamilton preferred a loose interpretation; he told Washington that Article 1, Section 8, empowered Congress to make “all Laws which shall be necessary and proper” to carry out the provisions of the Constitution. Agreeing with Hamilton, the president signed the legislation.

Raising Revenue Through Tariffs Hamilton now sought revenue to pay the annual interest on the national debt. At his insistence, Congress imposed excise taxes, including a duty on whiskey distilled in the United States. These taxes would yield $1 million a year. To raise another $4 million to $5 million, the treasury secretary proposed higher tariffs on foreign imports. Although Hamilton’s “Report on Manufactures” (1791) urged the expansion of American manufacturing, he did not support high protective tariffs that would exclude foreign products. Rather, he advocated moderate revenue tariffs that would pay the interest on the debt and other government expenses.

Hamilton’s scheme worked brilliantly. As American trade increased, customs revenue rose steadily and paid down the national debt. Controversies notwithstanding, the treasury secretary had devised a strikingly modern and successful fiscal system; as entrepreneur Samuel Blodget Jr. declared in 1801, “the country prospered beyond all former example.”

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

Why did Hamilton believe a national debt would strengthen the United States and help to ensure its survival?