America’s History: Printed Page 218

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 196

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 192

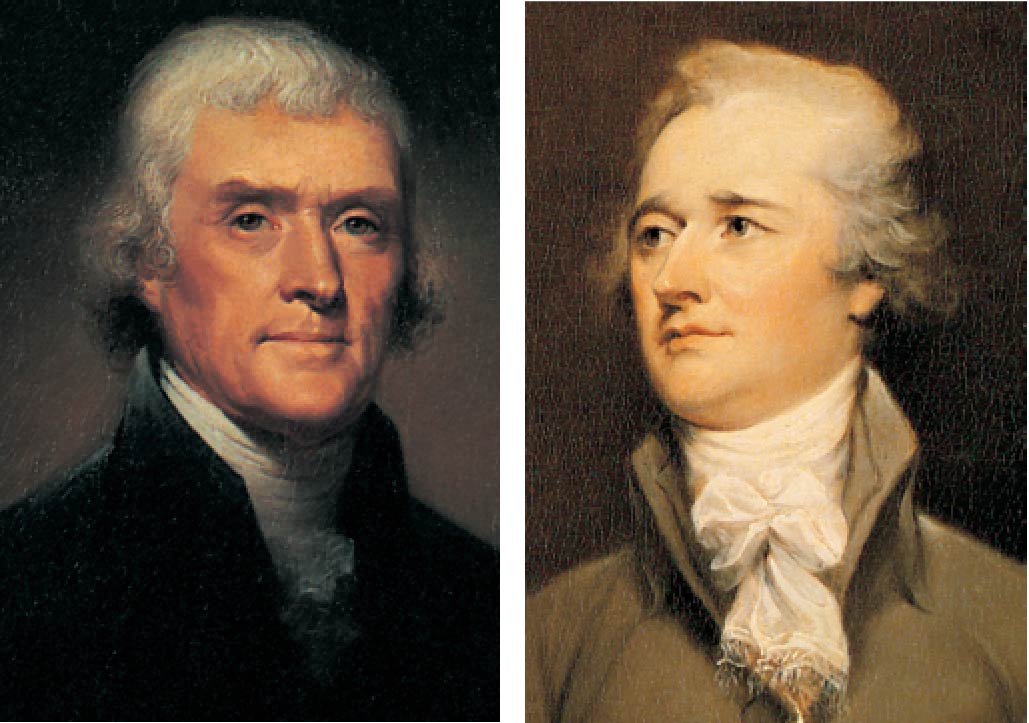

Jefferson’s Agrarian Vision

Hamilton paid a high political price for his success. As Washington began his second four-year term in 1793, Hamilton’s financial measures had split the Federalists into bitterly opposed factions. Most northern Federalists supported the treasury secretary, while most southern Federalists joined a group headed by Madison and Jefferson. By 1794, the two factions had acquired names. Hamiltonians remained Federalists; the allies of Madison and Jefferson called themselves Democratic Republicans or simply Republicans.

Thomas Jefferson spoke for southern planters and western farmers. Well-read in architecture, natural history, agricultural science, and political theory, Jefferson embraced the optimism of the Enlightenment. He believed in the “improvability of the human race” and deplored the corruption and social divisions that threatened its progress. Having seen the poverty of laborers in British factories, Jefferson doubted that wageworkers had the economic and political independence needed to sustain a republican polity.

Jefferson therefore set his democratic vision of America in a society of independent yeomen farm families. “Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God,” he wrote. The grain and meat from their homesteads would feed European nations, which “would manufacture and send us in exchange our clothes and other comforts.” Jefferson’s notion of an international division of labor resembled that proposed by Scottish economist Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations (1776).

|

To see a longer excerpt of Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, along with other primary sources from this period, see Sources for America’s History. |

Turmoil in Europe brought Jefferson’s vision closer to reality. The French Revolution began in 1789; four years later, the First French Republic (1792–1804) went to war against a British-led coalition of monarchies. As fighting disrupted European farming, wheat prices leaped from 5 to 8 shillings a bushel and remained high for twenty years, bringing substantial profits to Chesapeake and Middle Atlantic farmers. “Our farmers have never experienced such prosperity,” remarked one observer. Simultaneously, a boom in the export of raw cotton, fueled by the invention of the cotton gin and the mechanization of cloth production in Britain, boosted the economies of Georgia and South Carolina. As Jefferson had hoped, European markets brought prosperity to American agriculture.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

How did Jefferson’s idea of an agrarian republic differ from the economic vision put forward by Alexander Hamilton?