America’s History: Printed Page 219

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 197

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 193

The French Revolution Divides Americans

American merchants profited even more handsomely from the European war. In 1793, President Washington issued a Proclamation of Neutrality, allowing U.S. citizens to trade with all belligerents. As neutral carriers, American merchant ships claimed a right to pass through Britain’s naval blockade of French ports, and American firms quickly took over the lucrative sugar trade between France and its West Indian islands. Commercial earnings rose spectacularly, averaging $20 million annually in the 1790s — twice the value of cotton and tobacco exports. As the American merchant fleet increased from 355,000 tons in 1790 to 1.1 million tons in 1808, northern shipbuilders and merchants provided work for thousands of shipwrights, sailmakers, dockhands, and seamen. Carpenters, masons, and cabinetmakers in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia easily found work building warehouses and fashionable “Federal-style” town houses for newly affluent merchants.

Ideological Politics As Americans profited from Europe’s struggles, they argued passionately over its ideologies. Most Americans had welcomed the French Revolution (1789–1799) because it abolished feudalism and established a constitutional monarchy. The creation of the First French Republic was more controversial. Many applauded the end of the monarchy and embraced the democratic ideology of the radical Jacobins. Like the Jacobins, they formed political clubs and began to address one another as “citizen.” However, Americans with strong religious beliefs condemned the new French government for closing Christian churches and promoting a rational religion based on “natural morality.” Fearing social revolution at home, wealthy Americans condemned revolutionary leader Robespierre and his followers for executing King Louis XVI and three thousand aristocrats.

Their fears were well founded, because Hamilton’s economic policies quickly sparked a domestic insurgency. In 1794, western Pennsylvania farmers mounted the so-called Whiskey Rebellion to protest Hamilton’s excise tax on spirits (Thinking Like a Historian). This tax had cut demand for the corn whiskey the farmers distilled and bartered for eastern manufactures. Like the Sons of Liberty in 1765 and the Shaysites in 1786, the Whiskey Rebels assailed the tax collectors who sent the farmers’ hard-earned money to a distant government. Protesters waved banners proclaiming the French revolutionary slogan “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity!” To deter popular rebellion and uphold national authority, President Washington raised a militia force of 12,000 troops and dispersed the Whiskey Rebels.

Jay’s Treaty Britain’s maritime strategy intensified political divisions in America. Beginning in late 1793, the British navy seized 250 American ships carrying French sugar and other goods. Hoping to protect merchant property through diplomacy, Washington dispatched John Jay to Britain. But Jay returned with a controversial treaty that ignored the American claim that “free ships make free goods” and accepted Britain’s right to stop neutral ships. The treaty also required the U.S. government to make “full and complete compensation” to British merchants for pre–Revolutionary War debts owed by American citizens. In return, the agreement allowed Americans to submit claims for illegal seizures and required the British to remove their troops and Indian agents from the Northwest Territory. Despite Republican charges that Jay’s Treaty was too conciliatory, the Senate ratified it in 1795, but only by the two-thirds majority required by the Constitution. As long as the Federalists were in power, the United States would have a pro-British foreign policy.

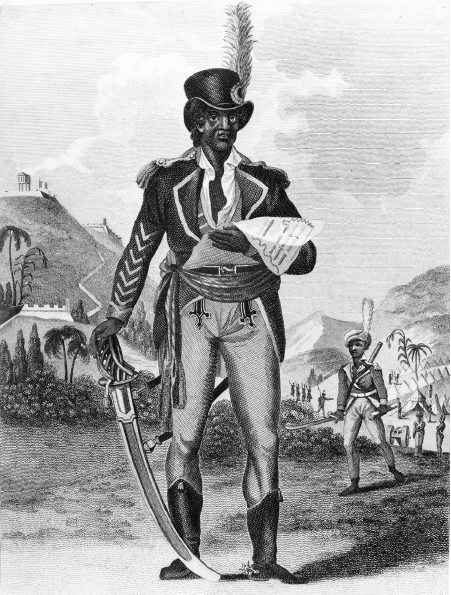

The Haitian Revolution The French Revolution inspired a revolution closer to home that would also impact the United States. The wealthy French plantation colony of Saint-Domingue in the West Indies was deeply divided: a small class of elite planters stood atop the population of 40,000 free whites and dominated the island’s half million slaves. In between, some 28,000 gens de couleur — free men of color — were excluded from most professions, forbidden from taking the names of their white relatives, and prevented from dressing and carrying themselves like whites. The French Revolution intensified conflict between planters and free blacks, giving way to a massive slave uprising in 1791 that aimed to abolish slavery. The uprising touched off years of civil war, along with Spanish and British invasions. In 1798, black Haitians led by Toussaint L’Ouverture — himself a former slave-owning planter — seized control of the country. After five more years of fighting, in 1803 Saint-Domingue became the independent nation of Haiti: the first black republic in the Atlantic World.

The Haitian Revolution profoundly impacted the United States. In 1793, thousands of refugees — planters, slaves, and free blacks alike — fled the island and traveled to Charleston, Norfolk, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, while newspapers detailed the horrors of the unfolding war. Many slaveholders panicked, fearful that the “contagion” of black liberation would undermine their own slave regimes. U.S. policy toward the rebellion presented a knotty problem. The first instinct of the Washington administration was to supply aid to the island’s white population. Adams — strongly antislavery and no friend of France — changed course, aiding the rebels and strengthening commercial ties. Jefferson, though sympathetic to moral arguments against slavery, was himself a southern slaveholder; he was, moreover, an ardent supporter of France. When he became president, he cut off aid to the rebels, imposed a trade embargo, and refused to recognize an independent Haiti. For many Americans, an independent nation of liberated citizen-slaves was a horrifying paradox, a perversion of the republican ideal (America Compared).

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

How did events abroad during the 1790s sharpen political divisions in the United States?