America’s History: Printed Page 257

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 229

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 224

Opportunity and Equality — for White Men

Between 1780 and 1820, hundreds of well-educated visitors agreed that the American social order was different from that of Europe. In his famous Letters from an American Farmer (1782), French-born essayist J. Hector St. Jean de Crèvecoeur wrote that European society was composed “of great lords who possess everything, and of a herd of people who have nothing.” By contrast, the United States had “no aristocratical families, no courts, no kings, no bishops.”

The absence of a hereditary aristocracy encouraged Americans to condemn inherited social privilege and to extol legal equality. “The law is the same for everyone,” noted one European traveler. Yet citizens of the new republic willingly accepted social divisions that reflected personal achievement, a phenomenon that astounded many Europeans. “In Europe to say of someone that he rose from nothing is a disgrace and a reproach,” remarked a Polish aristocrat. “It is the opposite here. To be the architect of your own fortune is honorable. It is the highest recommendation.”

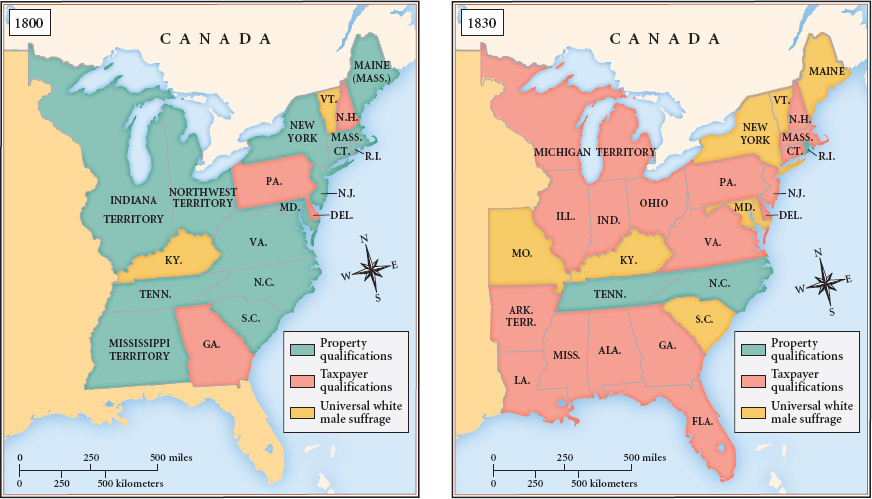

Some Americans from long-distinguished families felt threatened by the ideology of wealth-driven social mobility. “Man is estimated by dollars,” complained Nathaniel Booth, whose high-status family had once dominated the small Hudson River port town of Kingston, New York. However, for most white men, a merit-based system meant the chance to better themselves (Map 8.1).

Old cultural rules — and new laws — denied such chances to most women and African American men. When women and free blacks asked for voting rights, male legislators wrote explicit race and gender restrictions into the law. In 1802, Ohio disenfranchised African Americans, and the New York constitution of 1821 imposed a property-holding requirement on black voters. A striking case of sexual discrimination occurred in New Jersey, where the state constitution of 1776 had granted the voting franchise to all property holders. As Federalists and Republicans competed for power, they ignored customary gender rules and urged property-owning single women and widows to vote. Sensing a threat to men’s monopoly on politics, the New Jersey legislature in 1807 invoked both biology and custom to limit voting to men only: “Women, generally, are neither by nature, nor habit, nor education, nor by their necessary condition in society fitted to perform this duty with credit to themselves or advantage to the public.”

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

What factors encouraged — and inhibited — equality and democracy in early-nineteenth-century American life?