America’s History: Printed Page 270

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 243

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 236

A Republican Religious Order

The republican revolution of 1776 forced American lawmakers to devise new relationships between church and state. Previously, only the Quaker- and Baptist-controlled governments of Pennsylvania and Rhode Island had rejected a legally established church that claimed everyone as a member and collected compulsory religious taxes. Then, a convergence of factors — Enlightenment principles, wartime needs, and Baptist ideology — eliminated most state support for religion and allowed voluntary church membership.

Religious Freedom Events in Virginia revealed the dynamics of change. In 1776, James Madison and George Mason advanced Enlightenment ideas of religious toleration as they persuaded the state’s constitutional convention to guarantee all Christians the “free exercise of religion.” This measure, which ended the privileged legal status of the Anglican Church, won Presbyterian and Baptist support for the independence struggle. Baptists, who also opposed public support of religion, convinced lawmakers to reject a tax bill (supported by George Washington and Patrick Henry) that would have funded all Christian churches. Instead, in 1786, the Virginia legislature enacted Thomas Jefferson’s bill for Establishing Religious Freedom, which made all churches equal in the eyes of the law and granted direct financial support to none.

Elsewhere, the old order of a single established church crumbled away. In New York and New Jersey, the sheer number of denominations — Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Dutch Reformed, Lutheran, and Quaker, among others — prevented lawmakers from agreeing on an established church or compulsory religious taxes. Congregationalism remained the official church in the New England states until the 1830s, but members of other denominations could now pay taxes to their own churches.

Church-State Relations Few influential Americans wanted a complete separation of church and state because they believed that religious institutions promoted morality and governmental authority. “Pure religion and civil liberty are inseparable companions,” a group of North Carolinians advised their minister. “It is your particular duty to enlighten mankind with the unerring principles of truth and justice, the main props of all civil government.” Accepting this premise, most state governments indirectly supported churches by exempting their property and ministers from taxation.

Freedom of conscience also came with sharp cultural limits. In Virginia, Jefferson’s Religious Freedom act prohibited religious requirements for holding public office, but other states discriminated against those who were not Protestant Christians. The North Carolina Constitution of 1776 disqualified from public office any citizen “who shall deny the being of God, or the Truth of the Protestant Religion, or the Divine Authority of the Old or New Testament.” New Hampshire’s constitution contained a similar provision until 1868.

Americans influenced by Enlightenment deism and by evangelical Protestantism condemned these religious restrictions. Jefferson, Franklin, and other American intellectuals maintained that God had given humans the power of reason so that they could determine moral truths for themselves. To protect society from “ecclesiastical tyranny,” they demanded complete freedom of conscience. The “truth is great and will prevail if left to herself,” Jefferson declared; “religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God.” Many evangelical Protestants likewise demanded religious liberty to protect their churches from an oppressive government. Isaac Backus, a New England minister, warned Baptists not to incorporate their churches or accept public funds because that might lead to state control. In Connecticut, a devout Congregationalist welcomed “voluntarism,” the funding of churches by their members; it allowed the laity to control the clergy, he said, while also supporting self-government and “the principles of republicanism.”

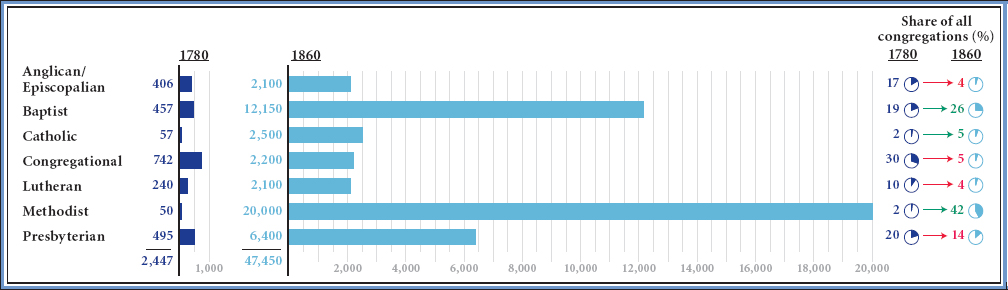

Republican Church Institutions Following independence, Americans embraced churches that preached spiritual equality and governed themselves democratically while ignoring those with hierarchical and authoritarian institutions. Preferring Luther’s doctrine of the priesthood of all believers, few citizens accepted the authority claimed by Roman Catholic priests and bishops. Likewise, few Americans joined the Protestant Episcopal Church, the successor to the Church of England, because wealthy lay members dominated many congregations and it, too, had a hierarchy of bishops (Figure 8.1). The Presbyterian Church attracted more adherents, in part because its churches elected lay members to synods, the congresses that determined doctrine and practice.

Evangelical Methodist and Baptist churches were by far the most successful institutions in attracting new members, especially from the “unchurched” — the great number of irreligious Americans. The Baptists boasted a thoroughly republican church organization, with self-governing congregations. Also, Baptists (and Methodists as well) developed an egalitarian religious culture marked by communal singing and emotional services. These denominations formed a dynamic new force in American religion.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

What were the main principles of the new republican religious regime?