America’s History: Printed Page 252

THINKING LIKE A HISTORIAN |  |

The Entrepreneur and the Community

Americans of the early republic believed that with hard work and virtue, even the lowliest of white men might rise to economic and political respectability, if not prominence. In the Revolutionary generation, Benjamin Franklin, born into a large and impoverished Boston family, had become a successful businessman and an international celebrity. Franklin’s success reflected the optimism that laboring men felt when contemplating the new nation’s seemingly boundless opportunity.

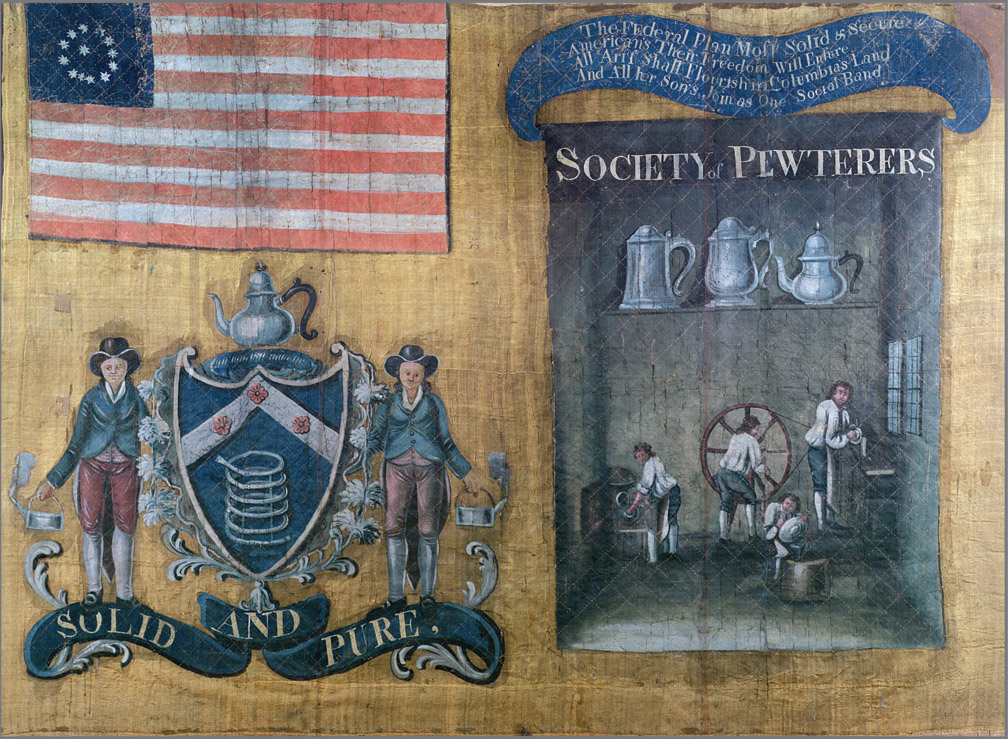

Banner of the Society of Pewterers of the City of New York, carried in the Federal Procession, July 23, 1788, celebrating the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. The ribbon at top right reads “The Federal Plan Most Solid & Secure/Americans Their Freedom Will Endure/All Art Shall Flourish in Columbia’s Land/And All her Sons Join as One Social Band.”

Source: © Collection of the New York Historical Society, USA/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Source: © Collection of the New York Historical Society, USA/The Bridgeman Art Library.John Jacob Astor quoted in Elbert Hubbard, Little Journeys to the Homes of Great Business Men, 1909. John Jacob Astor’s (1763–1848) story is a parable of American entrepreneurial triumph. Arriving in America in 1783 from Germany, Astor worked in the fur industry treating pelts and, with capital borrowed from his brother, started up a musical instrument shop and fur business in 1786. Over the next three decades, Astor’s American Fur Company prospered by trading furs in China, making Astor America’s first millionaire. Apparently influenced by Benjamin Franklin’s aphorism “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy wealthy and wise,” Astor wrote:

The man who makes it the habit of his life to go to bed at nine o’clock, usually gets rich and is always reliable. Of course, going to bed does not make him rich — I merely mean that such a man will in all probability be up early in the morning and do a big day’s work … good habits in America make any man rich.

Anonymous, “A Working Man’s Recollections of America,” Knight’s Penny Magazine, 1846. A cabinetmaker penned this account after returning to England following an unsuccessful stint seeking success in New York.

I was a cabinet-maker by trade, and one of the many who, between the years 1825–35, expatriated themselves in countless thousands, drawn by the promise of fair wages for faithful work, and driven by the scanty remuneration offered to unceasing toil at home. … On landing in New York I made up my mind to lose none of the advantages it uttered by want of diligence on my part. During the first two years I took but one holiday. … In summer we began work at six; at eight took half an hour for breakfast, and then worked till twelve, when one an hour for dinner; after which we kept on till six, seven, or eight. … A relative who arrived from England held out to me bright prospects of advantages to be realized by the employment of a little capital, combined with a removal to some inland town. I sold off nearly the whole of our moveables … [and committed all my savings to this enterprise. However,] our scheme … completely failed, and I had no resources but my industry and chest of tools to meet the impending difficulties.

Diary entry by Philip Hone, March 29, 1848. Philip Hone (1780–1851), a conservative Whig, was a successful merchant and entrepreneur and mayor of New York City from 1826 to 1827. Hone’s marvelous diary (1828–1851) records the changing character of New York City, as well as his contempt for Jacksonian Democracy and its Irish immigrant supporters.

John Jacob Astor died this morning, at nine o’clock, in the eighty-fifth year of his age … and left reluctantly his unbounded wealth. His property is estimated at $20,000,000, some judicious persons say $30,000,000; but, at any rate, he was the richest man in the United States in productive and valuable property; and this immense, gigantic fortune was the fruit of his own labor, unerring sagacity, and far-seeing penetration. He came to this country at twenty years of age; penniless, friendless, without inheritance, without education … but with a determination to be rich, and ability to carry it into effect. His capital consisted of a few trifling musical instruments, which he got from his brother, George Astor, in London, a dealer in music. … The fur trade was the philosopher’s stone of this modem Croesus; beaver-skins and musk-rats furnished the oil for the supply of Aladdin’s lamp. His traffic was the shipment of furs to China, where they brought immense prices, for he monopolized the business; and the return cargoes of teas, silks, and rich productions of China brought further large profits. … My brother and I found in Mr. Astor a valuable customer. … All he touched turned to gold.

Editorial in the New York Herald, April 5, 1848. John Jacob Astor’s will included a bequest of $400,000 for the establishment of what became the New York Public Library. This editorial questioned whether this relatively meager bequest adequately repaid residents.

If we had been an associate of John Jacob Astor the first idea that we should have put into his head would have been that one-half of his immense property — ten million at least — belonged to the people of the city of New York. During the last fifty years of the life of John Jacob Astor, his property has been augmented and increased in the value by the aggregate intelligence, industry, enterprise and commerce of New York, fully to the amount of one-half its value. The farms and lots of ground which he bought forty, twenty and ten and five years ago, have all increased in value entirely by the industry of the citizens of New York … half of his immense estate, in its actual value, has accrued to him by the industry of the community.

Sources: (2) Elbert Hubbard, Little Journeys to the Homes of Great Business Men (New York: Wm. H. Wise & Co., 1916), 201; (3) Knight’s Penny Magazine, Vol. 1 (London: Charles Knight & Co., 1846), 97, 107, 108; (4) Philip Hone, The Diary of Philip Hone, 1828–1851, Vol. 2 (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1889), 347–348; (5) Gustavus Myers, History of the Great American Fortunes, Vol. 1 (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1910), 199–200.

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

Question

What does the Pewterer’s Banner (source 1) suggest about personal and by extension national success in the post-Revolutionary era? What can you infer about artisan entrepreneurs in the new republic from this source?

Question

According to John Jacob Astor (source 2) and the cabinetmaker (source 3), what traits are important in work? Based on the sources included here, do you agree with Astor that good habits make any man rich? Why or why not?

Question

Sources 2, 4, and 5 all deal with John Jacob Astor. What do these sources suggest about the road to wealth in America?

Question

Compare and contrast Hone’s view of Astor (source 4) with that of the Herald’s editorial (source 5). Then apply the Herald’s critique to contemporary entrepreneurs such as Bill Gates of Microsoft or Steve Jobs of Apple. Are their fortunes also the product, in part, of “the industry of the community”?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Question

John Jacob Astor initially made money by trading furs in local and then in international markets. Next, he speculated in land in booming cities. Finally, he became a rentier, crafting long-term property leases that guaranteed wealth to future generations of his family. Using the material in Chapter 8, explain how a pewterer or a cabinetmaker might follow a somewhat similar path to wealth in the market economy of nineteenth-century America. Noting also the statement “All her Sons Join as One Social Band” (source 1), explain why other Americans were critical of the rise of such ambitious capitalist entrepreneurs.