America’s History: Printed Page 293

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 268

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 259

The Transportation Revolution Forges Regional Ties

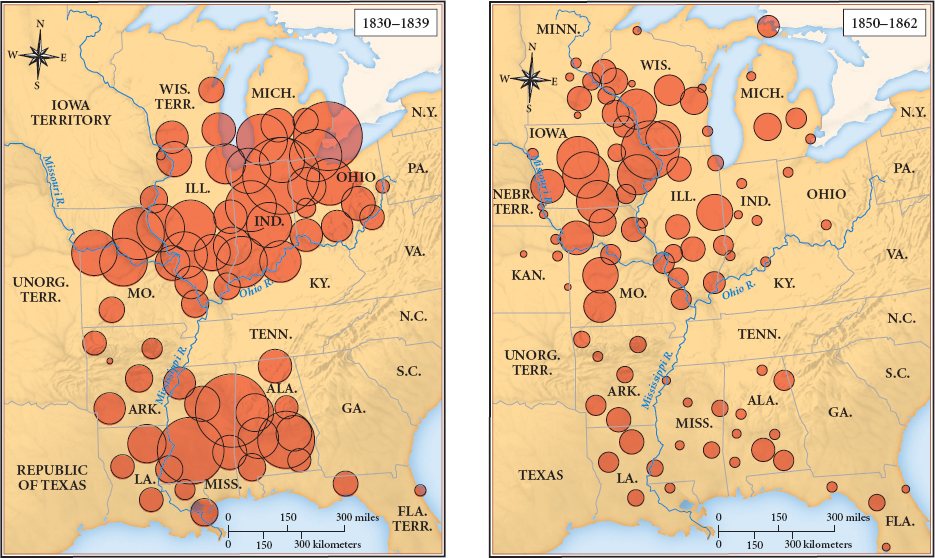

With the Indian peoples in retreat, slave-owning planters from the Lower South settled in Missouri (admitted to the Union in 1821) and pushed on to Arkansas (admitted in 1836). Simultaneously, yeomen families from the Upper South joined migrants from New England and New York in farming the fertile lands near the Great Lakes. Once Indiana and Illinois were settled, land-hungry farmers poured into Michigan (1837), Iowa (1846), and Wisconsin (1848) — where they resided among tens of thousands of hardworking immigrants from Germany. To meet the demand for cheap farmsteads, Congress in 1820 reduced the price of federal land from $2.00 an acre to $1.25. For $100, a farmer could buy 80 acres, the minimum required under federal law. By the 1840s, this generous policy had enticed about 5 million people to states and territories west of the Appalachians (Map 9.2).

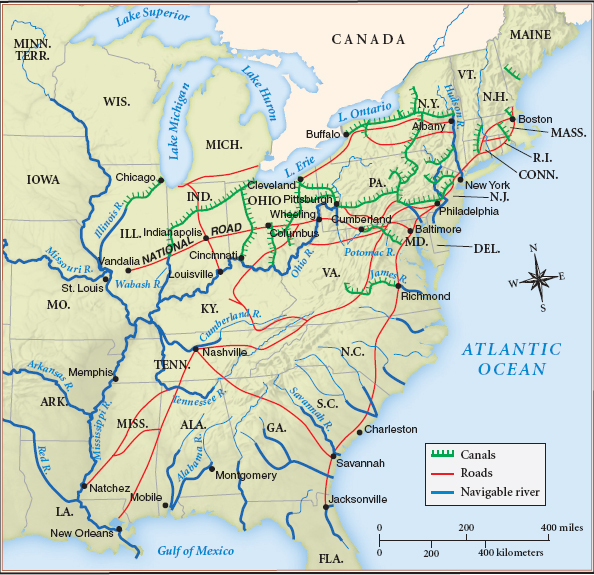

To link the midwestern settlers to the seaboard states, Congress approved funds for a National Road constructed of compacted gravel. The project began in 1811 at Cumberland in western Maryland, at the head of navigation of the Potomac River; reached Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia), on the Ohio River in 1818; and ended in Vandalia, Illinois, in 1839. The National Road and other interregional highways carried migrants and their heavily loaded wagons westward; these migrants passed livestock herds heading in the opposite direction, destined for eastern markets. To link the settler communities with each other, state legislatures chartered private companies to build toll roads, or turnpikes.

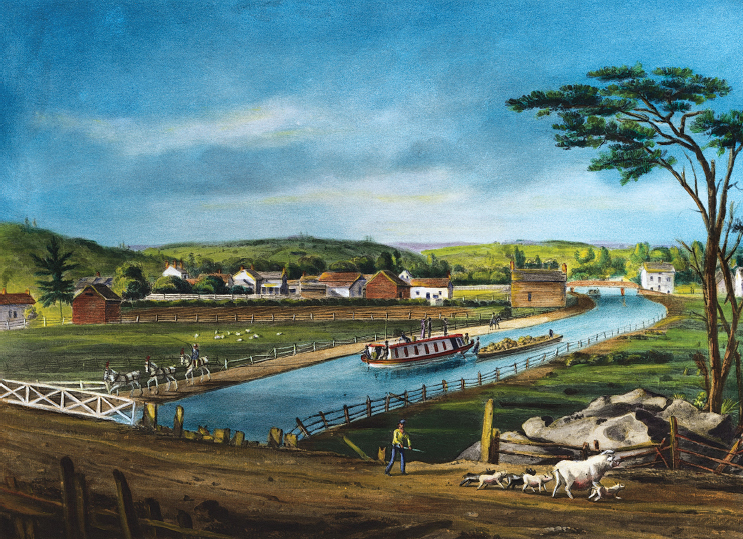

Canals and Steamboats Shrink Distance Even on well-built gravel roads, overland travel was slow and expensive. To carry people, crops, and manufactures to and from the great Mississippi River basin, public money and private businesses developed a water-borne transportation system of unprecedented size, complexity, and cost. The key event was the New York legislature’s 1817 financing of the Erie Canal, a 364-mile waterway connecting the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Previously, the longest canal in the United States was just 28 miles long — reflecting the huge capital cost of canals and the lack of American engineering expertise. New York’s ambitious project had three things working in its favor: the vigorous support of New York City’s merchants, who wanted access to western markets; the backing of New York’s governor, De Witt Clinton, who proposed to finance the waterway from tax revenues, tolls, and bond sales to foreign investors; and the relatively gentle terrain west of Albany. Even so, the task was enormous. Workers — many of them Irish immigrants — dug out millions of cubic yards of soil, quarried thousands of tons of rock for the huge locks that raised and lowered the boats, and constructed vast reservoirs to ensure a steady supply of water.

The first great engineering project in American history, the Erie Canal altered the ecology of an entire region. As farming communities and market towns sprang up along the waterway, settlers cut down millions of trees to provide wood for houses and barns and to open the land for growing crops and grazing animals. Cows and sheep foraged in pastures that had recently been forests occupied by deer and bears, and spring rains caused massive erosion of the denuded landscape.

Whatever its environmental consequences, the Erie Canal was an instant economic success. The first 75-mile section opened in 1819 and quickly yielded enough revenue to repay its construction cost. When workers finished the canal in 1825, a 40-foot-wide ribbon of water stretched from Buffalo, on the eastern shore of Lake Erie, to Albany, where it joined the Hudson River for the 150-mile trip to New York City. The canal’s water “must be the most fertilizing of all fluids,” suggested novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, “for it causes towns with their masses of brick and stone, their churches and theaters, their business and hubbub, their luxury and refinement, their gay dames and polished citizens, to spring up.”

The Erie Canal brought prosperity to the farmers of central and western New York and the entire Great Lakes region. Northeastern manufacturers shipped clothing, boots, and agricultural equipment to farm families; in return, farmers sent grain, cattle, and hogs as well as raw materials (leather, wool, and hemp, for example) to eastern cities and foreign markets. One-hundred-ton freight barges, each pulled by two horses, moved along the canal at a steady 30 miles a day, cutting transportation costs and accelerating the flow of goods. In 1818, the mills in Rochester, New York, processed 26,000 barrels of flour for export east (and north to Montreal, for sale as “Canadian” produce to the West Indies); ten years later, their output soared to 200,000 barrels; and by 1840, it was at 500,000 barrels.

The spectacular benefits of the Erie Canal prompted a national canal boom. Civic and business leaders in Philadelphia and Baltimore proposed waterways to link their cities to the Midwest. Copying New York’s fiscal innovations, they persuaded their state legislatures to invest directly in canal companies or to force state-chartered banks to do so. They also won state guarantees that encouraged British and Dutch investors; as one observer noted in 1844, “The prosperity of America, her railroads, canals, steam navigation, and banks, are the fruit of English capital.” Soon, artificial waterways connected Philadelphia and Baltimore, via the Pennsylvania Canal and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, to the Great Lakes region.

Equally important was the vast network of navigable rivers that drained into the Mississippi. Every year, 25,000 farmer-built flatboats used these waterways to carry produce to New Orleans. In 1848, the completion of the Michigan and Illinois Canal, which linked Chicago to the Mississippi River, completed an inland all-water route from New York City to New Orleans, the two most important port cities in North America (Map 9.3).

The steamboat, another product of the industrial age, added crucial flexibility to the Mississippi basin’s river-based transportation system. In 1807, engineer-inventor Robert Fulton built the first American steamboat, the Clermont, which he piloted up the Hudson River. To navigate shallow western rivers, engineers broadened steamboats’ hulls to reduce their draft and enlarge their cargo capacity. These improved vessels halved the cost of upstream river transport along the Mississippi River and its tributaries and dramatically increased the flow of goods, people, and news. In 1830, a traveler or a letter from New York could reach Buffalo or Pittsburgh by water in less than a week and Detroit, Chicago, or St. Louis in two weeks. In 1800, the same journeys had taken twice as long.

The state and national governments played key roles in developing this interregional network of trade and travel. State legislatures subsidized canals, while the national government created a vast postal system, the first network for the exchange of information. Thanks to the Post Office Act of 1792, there were more than eight thousand post offices by 1830, and they safely delivered thousands of letters and banknotes worth millions of dollars. The U.S. Supreme Court, headed by John Marshall, likewise encouraged interstate trade by firmly establishing federal authority over interstate commerce. In Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), the Court voided a New York law that created a monopoly on steamboat travel into New York City. That decision prevented local or state monopolies — or tariffs — from impeding the flow of goods, people, and news across the nation.

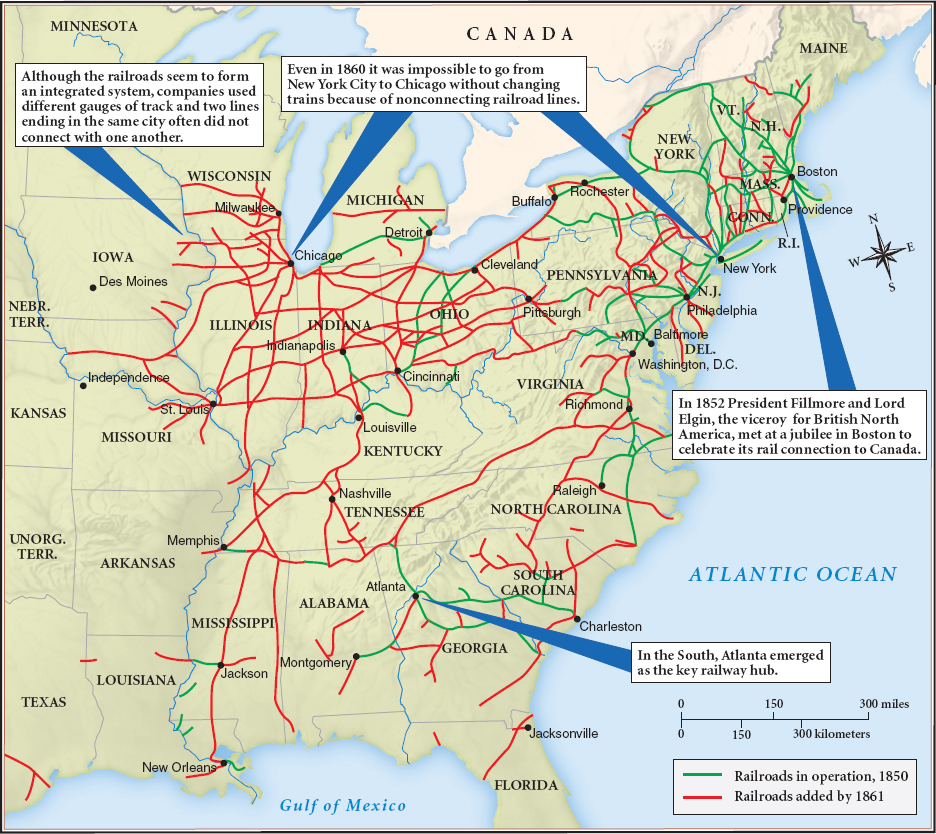

Railroads Link the North and Midwest In the 1850s, railroads, another technological innovation, joined canals as the core of the national transportation system (Map 9.4). In 1852, canals carried twice the tonnage transported by railroads. Then, capitalists in Boston, New York, and London secured state charters for railroads and invested heavily in new lines, which by 1860 had become the main carriers of wheat and freight from the Midwest to the Northeast. Serviced by a vast network of locomotive and freight-car repair shops, the Erie, Pennsylvania, New York Central, and the Baltimore and Ohio railroads connected the Atlantic ports — New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore — with the rapidly expanding Great Lakes cities of Cleveland and Chicago (Thinking Like a Historian).

The railroad boom also linked these western cities to adjacent states. Chicago-based railroads carried huge quantities of lumber from Michigan to the treeless prairies of Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri, where settlers built 250,000 new farms (covering 19 million acres) and hundreds of small towns. On their return journey, the trains moved millions of bushels of wheat to Chicago for transport to eastern markets. Increasingly, they also carried livestock to Chicago’s slaughterhouses. In Jacksonville, Illinois, a farmer decided to feed his entire corn crop of 1,500 bushels “to hogs & cattle, as we think it is more profitable than to sell the corn.” A Chicago newspaper boasted, “In ancient times all roads led to Rome; in modern times all roads lead to Chicago.”

Initially, midwestern settlers relied on manufactured goods imported from the Northeast. They bought high-quality shovels and spades fabricated at the Delaware Iron Works and the Oliver Ames Company in Easton, Massachusetts; axes forged in Connecticut factories; and steel horseshoes manufactured in Troy, New York. However, by the 1840s, midwestern entrepreneurs were also producing machine tools, hardware, furniture, and especially agricultural implements. Working as a blacksmith in Grand Detour, Illinois, John Deere made his first steel plow out of old saws in 1837; ten years later, he opened a factory in Moline, Illinois, that mass-produced the plows. Stronger than the existing cast-iron models built in New York, Deere’s steel plows allowed farmers to cut through the thick sod of the prairies. Other midwestern companies — such as McCormick and Hussey — mass-produced self-raking reapers that harvested 12 acres of grain a day (rather than the 2 acres that an adult worker could cut by hand). With the harvest bottleneck removed, farmers planted more acres and grew even more wheat. Flour soon accounted for 10 percent of all American exports to foreign markets.

Interregional trade also linked southern cotton planters to northeastern textile plants and foreign markets. This commerce in raw cotton bolstered the wealth of white southerners but did not transform their economic and social order as it did in the Midwest. With the exception of Richmond, Virginia, and a few other places, southern planters did not invest their profits in manufacturing. Lacking cities, factories, and highly trained workers, the South remained tied to agriculture, even as the commerce in wheat, corn, and livestock promoted diversified economies in the Northeast and Midwest.

IDENTIFY CAUSES

Question

Which was more important in the Market Revolution, government support for transportation or technological innovations, and why was that the case?