America’s History: Printed Page 297

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 273

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 264

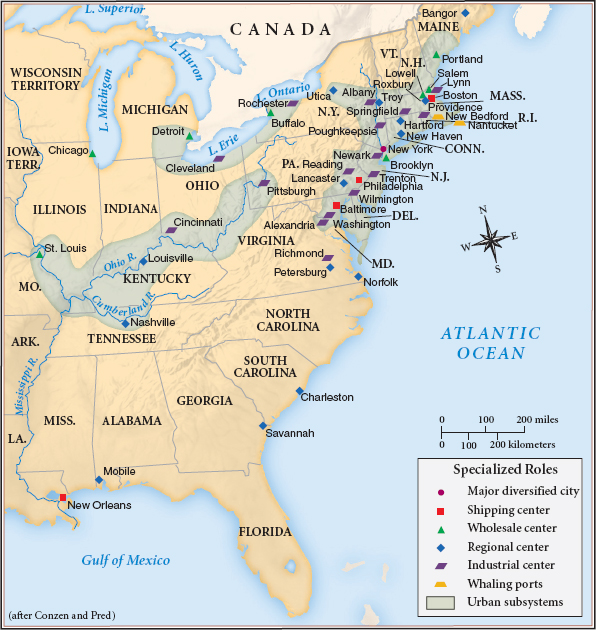

The Growth of Cities and Towns

The expansion of industry and trade dramatically increased America’s urban population. In 1820, there were 58 towns with more than 2,500 inhabitants; by 1840, there were 126 such towns, located mostly in the Northeast and Midwest. During those two decades, the total number of city dwellers grew more than fourfold, from 443,000 to 1,844,000.

The fastest growth occurred in the new industrial towns that sprouted along the “fall line,” where rivers descended rapidly from the Appalachian Mountains to the coastal plain. In 1822, the Boston Manufacturing Company built a complex of mills in a sleepy Merrimack River village that quickly became the bustling textile factory town of Lowell, Massachusetts. The towns of Hartford, Connecticut; Trenton, New Jersey; and Wilmington, Delaware, also became urban centers as mill owners exploited the water power of their rivers and recruited workers from the countryside.

Western commercial cities such as Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and New Orleans grew almost as rapidly. These cities expanded initially as transit centers, where workers transferred goods from farmers’ rafts and wagons to steamboats or railroads. As the midwestern population grew during the 1830s and 1840s, St. Louis, Detroit, and especially Buffalo and Chicago also emerged as dynamic centers of commerce. “There can be no two places in the world,” journalist Margaret Fuller wrote from Chicago in 1843, “more completely thoroughfares than this place and Buffalo. … The life-blood [of commerce] rushes from east to west, and back again from west to east.” To a German visitor, Chicago seemed “for the most part to consist of shops … [as if] people came here merely to trade, to make money, and not to live.” Chicago’s merchants and bankers developed the marketing, provisioning, and financial services essential to farmers and small-town shopkeepers in its vast hinterland. “There can be no better [market] any where in the Union,” declared a farmer in Paw Paw, Illinois.

These midwestern hubs quickly became manufacturing centers. Capitalizing on the cities’ links to rivers, canals, and railroads, entrepreneurs built warehouses, flour mills, packing plants, and machine shops, creating work for hundreds of artisans and factory laborers. In 1846, Cyrus McCormick moved his reaper factory from western Virginia to Chicago to be closer to his midwestern customers. By 1860, St. Louis and Chicago had become the nation’s eighth- and ninth-largest cities; by 1870, they were the fourth and fifth, behind New York, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn (Map 9.5).

The old Atlantic seaports — Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, and especially New York City — remained important for their foreign commerce and, increasingly, as centers of finance and small-scale manufacturing. New York City and nearby Brooklyn grew at a phenomenal rate: between 1820 and 1860, their combined populations increased nearly tenfold to 1 million people, thanks to the arrival of hundreds of thousands of German and Irish immigrants. Drawing on these workers, New York became a center of the ready-made clothing industry, which relied on thousands of low-paid seamstresses. “The wholesale clothing establishments are … absorbing the business of the country,” a “Country Tailor” complained to the New York Tribune, “casting many an honest and hardworking man out of employment [and helping] … the large cities to swallow up the small towns.”

New York City’s growth stemmed primarily from its dominant position in foreign and domestic trade. It had the best harbor in the United States and, thanks to the Erie Canal, was the best gateway to the Midwest and the best outlet for western grain. Recognizing the city’s advantages, in 1818 four English Quaker merchants founded the Black Ball Line to carry cargo, people, and mail between New York and London, Liverpool, and Le Havre, establishing the first regularly scheduled transatlantic shipping service. By 1840, its port handled almost two-thirds of foreign imports into the United States, almost half of all foreign trade, and much of the immigrant traffic. New York likewise monopolized trade with the newly independent South American nations of Brazil, Peru, and Venezuela, and its merchants took over the trade in cotton by offering finance, insurance, and shipping to southern planters and merchants.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Question

What different types of cities emerged between 1820 and 1860, and what caused their growth?