America’s History: Printed Page 4

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 3

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 3

Experimentation and Transformation

The Granger Collection, New York.

The Granger Collection, New York.

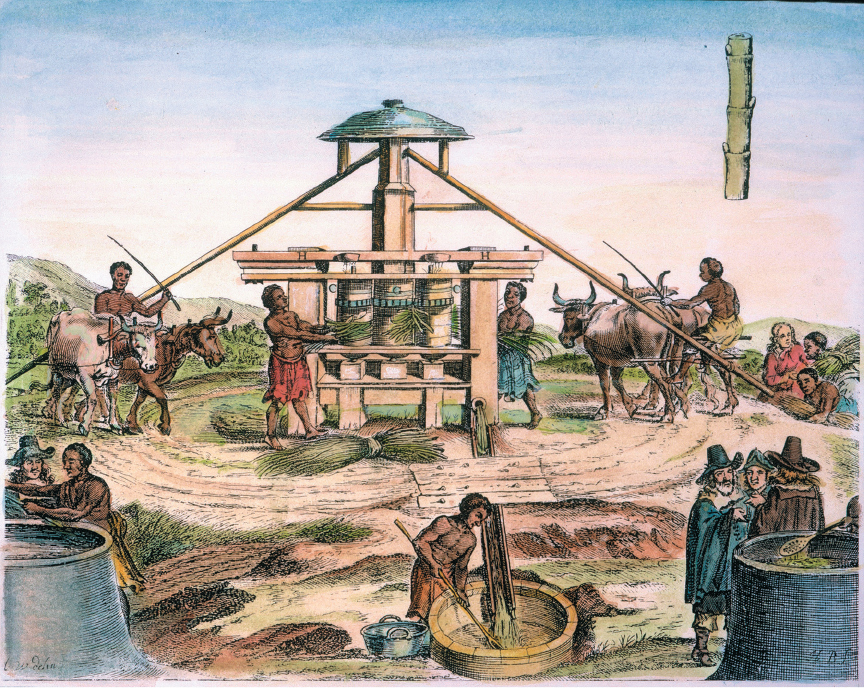

The collisions of American, European, and African worlds challenged the beliefs and practices of all three groups. Colonization was, above all, a long and tortured process of experimentation. Over time, Europeans carved out three distinct types of colonies in the Americas, each shaped by the constraints and opportunities presented by American landscapes and peoples. Where Native American societies were organized into densely settled empires, Europeans conquered the ruling class and established tribute-based empires of their own. In tropical and subtropical settings, colonizers created plantation societies that demanded large, imported labor forces — a need that was met through the African slave trade. And in the temperate regions of the mainland North America, where neither the landscape nor the native population yielded easy wealth, European colonists came in large numbers hoping to create familiar societies in unfamiliar settings.

Everywhere in the Americas, core beliefs and worldviews were shaken by contact with radically unfamiliar peoples. Native Americans and Africans struggled to maintain autonomy in their relations with colonizers, while Europeans labored to understand — and profit from — their relations with nonwhite peoples. These transformations are the subject of Part 1.