America’s History: Printed Page 77

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 64

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 62

The Diversification of British North America

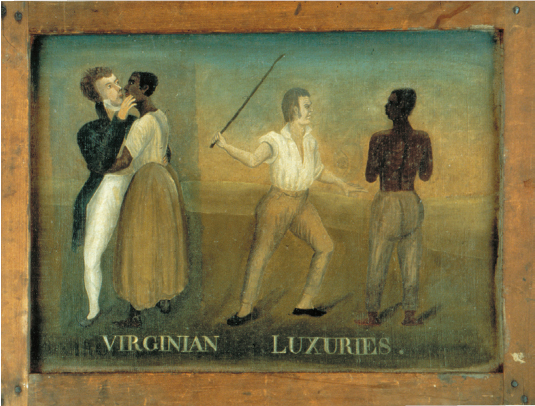

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Williamsburg, VA.

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Williamsburg, VA.

The American colonies of the various European nations gradually diverged from each other in character. The tribute-based societies at the core of Spain’s empire developed into complex multiracial societies; Portuguese Brazil was dominated by its plantation and mining enterprises; the Dutch largely withdrew their energies from the Americas, except for a few plantation colonies; the French, too, developed several important plantation colonies in the West Indies but struggled to populate their vast North American holdings. The population of Britain’s colonies, by contrast, grew and diversified after 1660. Britain came to dominate the Atlantic slave trade and brought more than two million slaves to its American colonies. The great majority went to Jamaica, Barbados, and the other sugar islands, but half a million found their way to the mainland, where, by 1763, they constituted nearly 20 percent of the mainland colonies’ populations. Slavery was a growing and thriving institution in British North America.

Non-English Europeans also crossed the Atlantic in very large numbers. The ethnic landscape of Britain’s mainland colonies was dramatically altered by 115,000 migrants from Ireland (most of them Scots-Irish Presbyterians) and 100,000 Germans. Most immigrated to Pennsylvania, which soon had the most ethnically diverse population of Europeans on the continent. Relations among these groups were often divisive, as each struggled to maintain its identity and autonomy in a rapidly changing landscape.