America’s History: Printed Page 147

America: A Concise History: Printed Page 129

America’s History: Value Edition: Printed Page 126

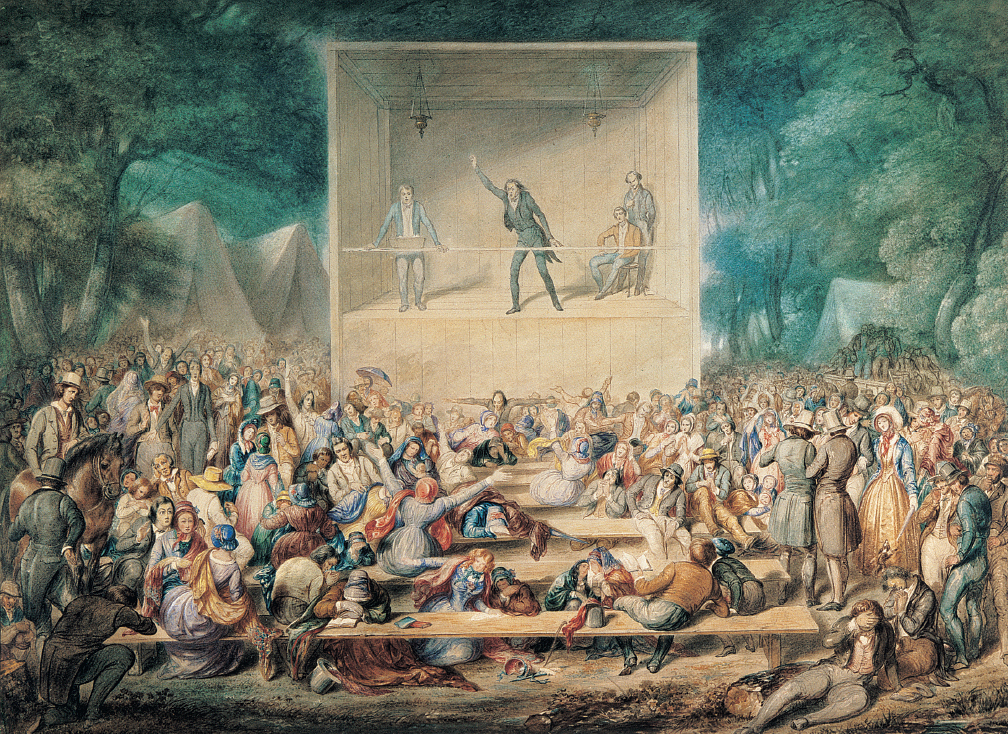

Challenges to the Social Order

Old Dartmouth Historical Society/New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Old Dartmouth Historical Society/New Bedford Whaling Museum.

As Patriots articulated values they associated with independence, they aligned their movement with currents of reform eddying through the Atlantic World: antislavery; women’s rights; religious liberty; social equality. Each of these ideas was controversial, and the American Revolution endorsed none of them in an unqualified way. But its idealism — the sense that the Revolution marked “a memorable epoch in the annals of the human race,” as John Adams put it — made the era malleable and full of possibility.

Legislatures abolished slavery in the North, broadened religious liberty by allowing freedom of conscience, and, except in New England, ended the system of legally established churches. Postwar evangelicalism gave enormous energy to a new wave of innovative religious developments. However, Americans continued to argue over social equality, in part because their republican creed placed family authority in the hands of men and political power in the hands of propertied individuals: this arrangement denied power and status not only to slaves but also to free blacks, women, and middling and poor white men. Though the Revolution’s legacy was mixed, its meaning would be debated for decades in American public life.