Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 301

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 253

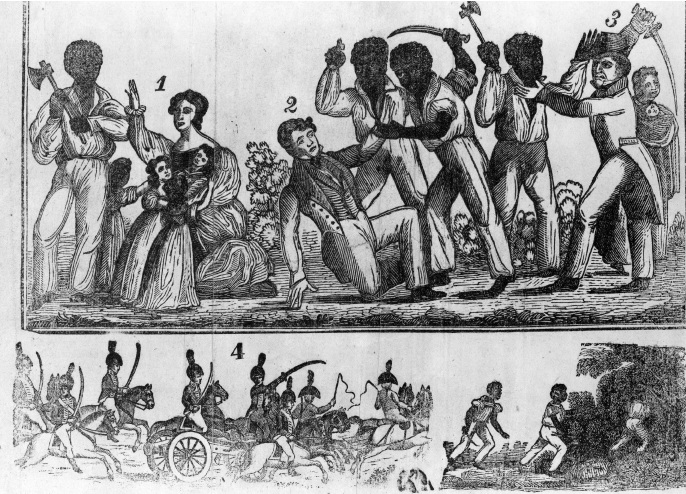

Resistance and Rebellion

Many owners worried that black preachers and West African folktales inspired blacks to resist enslavement. Fearing defiance, planters went to incredible lengths to control seemingly powerless slaves. Although they were largely successful in quelling open revolts, they were unable to eliminate more subtle forms of opposition, like slowing the pace of work, feigning illness, and damaging white-owned equipment, food, and clothing. Even slaves’ ability to sustain a distinct African American culture was viewed by some planters as undermining the institution of bondage. More overt forms of resistance—such as truancy and running away, which disrupted work and lowered profits—also proved impossible to stamp out.

The forms of everyday resistance slaves employed varied in part on their location and resources. Skilled artisans, mostly men, could do more substantial damage because they used more expensive tools, but they were less able to protect themselves through pleas of ignorance. Field laborers could damage only hoes and a few cotton plants, but they could do so on a regular basis without exciting suspicion. House slaves could burn dinners, scorch shirts, break china and glassware, and even poison owners or burn down houses. Often considered the most loyal slaves, they were also among the most feared because of their intimate contact with white families. Single male slaves were the most likely to run away, planning their escape carefully to get as far as possible before their owners noticed they were missing. Women who fled plantations were more likely to hide out for short periods in the local area and return at night to get food and visit family. Eventually, isolation, hunger, or concern for children led most of these truants to return if slave patrols did not find them first.

Despite their rarity, efforts to organize slave uprisings, such as that planned by Gabriel (see chapter 8) and the one supposedly hatched by Denmark Vesey (see chapter 9) in the early nineteenth century, continued to haunt southern whites. Rebellions in the West Indies, especially the one in Saint Domingue, also echoed through the early nineteenth century. Then in 1831 a seemingly obedient slave named Nat Turner organized a revolt in rural Virginia that stunned whites across the South. Turner was a self-styled preacher and religious visionary who believed that God had given him a mission. On the night of August 21, he and his followers killed their owners, the Travis family, and then headed to nearby plantations in Southampton County. The bloody insurrection led to the deaths of 57 white men, women, and children and liberated more than 50 slaves. But on August 22, outraged white militiamen burst on the scene and eventually captured the black rebels. Turner managed to hide out for two months but was eventually caught. Tried and convicted on November 5, he was hanged six days later. Virginia executed 55 other African Americans suspected of assisting Turner. White mobs also beat, tortured, or killed some 200 more blacks with no connection to the rebellion.

Nat Turner’s rebellion instilled panic among white Southerners, who now worried they might be killed in their sleep by a seemingly submissive slave. News of the uprising traveled through slave communities as well, inspiring both pride and anxiety. The execution of Turner and his followers reminded African Americans how far whites would go to protect the institution of slavery.

Review & Relate

|

How did enslaved African Americans create ties of family, community, and culture? |

How did enslaved African Americans resist efforts to control and exploit their labor? |