Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 303

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 256

White Southerners without Slaves

Yeomen farmers, independent landowners who did not own any slaves, had a complex relationship with the South’s plantation economy. Many were related to slave owners, and they often depended on planters to ship their crops to market. Some hoped to rise into the ranks of slaveholders one day, and others made extra money by hiring themselves out to planters. Yet yeomen farmers also recognized that their economic interests often diverged from those of planters. As growing numbers gained the right to vote in the 1820s and 1830s, they voiced their concerns in county and state legislatures.

Most yeomen farmers believed in slavery, but they sometimes challenged planters’ authority and assumptions. In the Virginia slavery debates, small farmers from western districts advocated gradual abolition. In other states, they advocated more liberal policies toward debtors and the protection of fishing rights. Yeomen farmers also questioned certain ideals embraced by elites. Although plantation mistresses considered manual labor beneath them, the wives and daughters of many small farmers had to work in the fields, haul water, chop wood, and perform other arduous tasks. Still, yeomen farmers’ ability to diminish planter control was limited by the continued importance of cotton to the southern economy.

In their daily life, however, many small farmers depended more on friends and neighbors than on the planter class. Barn raisings, corn shuckings, quilting bees, and other collective endeavors offered them the chance to combine labor with sociability. Church services and church socials also brought communities together. Farmers lost such ties when they sought better land on the frontier. There, families struggled to establish new crops and new lives in relative isolation but hoped that fertile fields might offer the best chance to rise within the South’s rigid class hierarchy.

One step below the yeomen farmers were the even larger numbers of white Southerners who owned no property at all. These poor whites depended on hunting and fishing in frontier areas, performing day labor on farms and plantations, or working on docks or as servants in southern cities. Poor whites competed with free blacks and slaves for employment and often harbored resentments as a result. Yet they also built alliances based on their shared economic plight. Poor immigrants from Ireland, Wales, and Scotland were especially hostile to American planters, who reminded them of English landlords.

Some poor whites remained in the same community for decades, establishing themselves on the margins of society. They attended church regularly, performed day labor for affluent families, and taught their children to defer to their betters. In Savannah and other southern cities, wealthy families organized benevolent associations and more affluent immigrants established mutual aid societies to help poorer members of their community in hard times. It was the most respectable among this downtrodden class who had the best chance of securing assistance.

Other poor whites moved frequently and survived by combining legal and illegal ventures. Some rejected laws and customs established by elites and joined forces with blacks or other poor whites. These men and women often had few ties to local communities, little religious training or education, and settled scores with violence. Although poor whites unnerved southern elites by flouting the law and sometimes befriending poor blacks, they could not mount any significant challenge to planter control.

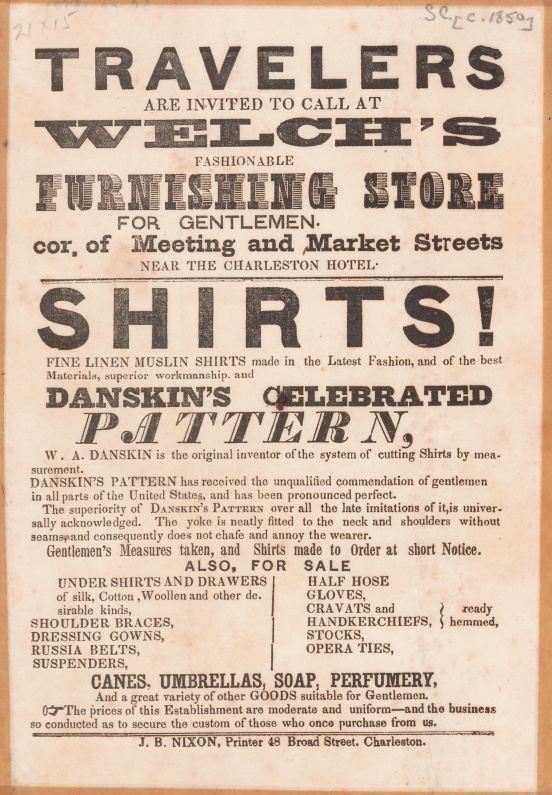

Unlike poor whites, the South’s small but growing middle class sought stability and respectability. These middle-class Southerners, who worked as doctors, lawyers, journalists, teachers, and shopkeepers, often looked to the North for models to emulate. Many were educated in northern schools and developed ties with their commercial or professional counterparts in northern cities. They were avid readers of newspapers, religious tracts, and literary periodicals published in the North. And like middle-class Northerners, southern businessmen often depended on their wives’ social and financial skills to succeed.

Nonetheless, middle-class southern men shared many of the social attitudes and political priorities of slave owners. They participated alongside planters in benevolent associations, literary and temperance (antialcohol) societies, and agricultural reform organizations. Most middle-class Southerners also adamantly supported slavery and benefited from planters’ demands for goods and services. In fact, some suggested that bound labor might be as useful to industry as it was to agriculture, and they sought to expand the institution further. Despite the emergence of a small middle class, however, the gap between rich and poor continued to expand in the South.