Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 295

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 248

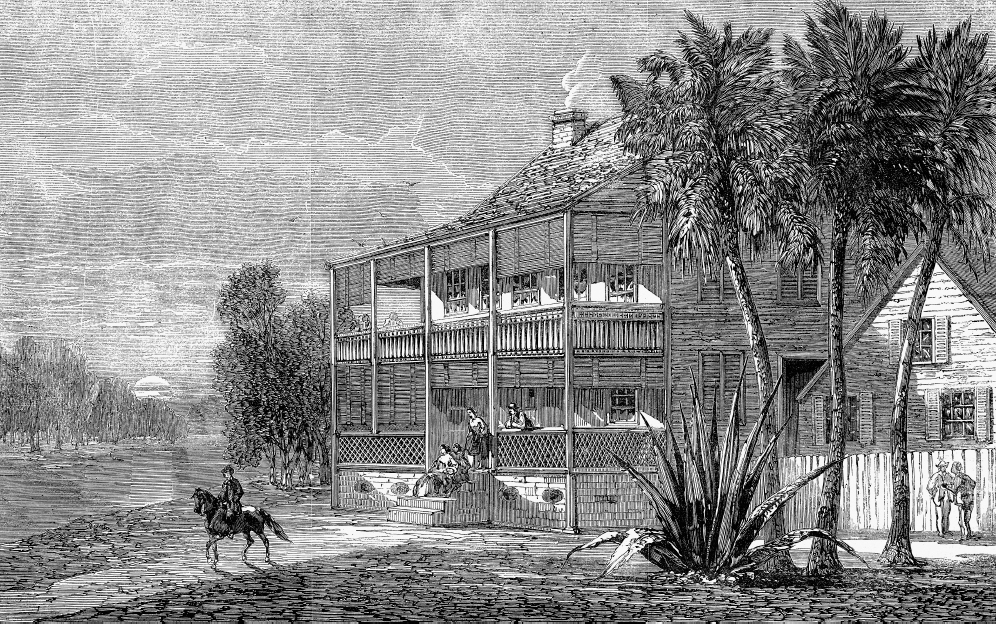

A Plantation Society Develops in the South

Plantation slavery existed throughout the Americas in the early nineteenth century. British, French, Dutch, Portuguese, and Spanish colonies in the West Indies and South America all housed large numbers of slaves and extensive plantations. In the U.S. South, however, the volatile cotton market and a scarcity of fertile land kept most plantations relatively small before 1830. But from the early 1840s on, territorial expansion and profits from cotton, as well as from rice and sugar, fueled a period of conspicuous consumption. Successful southern planters now built grand houses and purchased a variety of luxury goods.

As plantations grew, especially in states like South Carolina and Mississippi where slaves outnumbered whites, a wealthy aristocracy sought to ensure productivity by employing harsh methods of discipline. Masters whipped slaves for a variety of offenses, from not picking enough cotton to breaking tools or running away. Although James Henry Hammond imagined himself a progressive master, he used the whip liberally, hoping thereby to ensure that his estate generated sufficient profits to purchase fancy furnishings, trips to Europe, fashionable clothing, and fine jewelry.

Increased attention to comfort and luxury helped make the heavy workload of plantation mistresses tolerable. Although mistresses were idealized for their beauty, piety, and grace, they took on considerable managerial responsibilities. They directed the domestic slaves as well as the feeding, clothing, and medical care of the entire labor force. They were expected to organize and preside over lavish social events, host relatives and friends for extended stays, and direct the plantation in their husband’s absence. When James was traveling, Catherine Hammond struggled to manage the estate while caring for their seven children.

Of course, plantation mistresses were relieved of the most arduous labor by enslaved women, who cooked, cleaned, and washed for the family, cared for the children, and even nursed the babies. Wealthy white women benefited from the best education, the greatest access to music and literature, and the finest clothes and furnishings to be had in the region. Yet the pedestal on which plantation mistresses stood was shaky, built on a patriarchal system in which husbands and fathers held substantial power. For example, most wives were forced to ignore the sexual relations that husbands initiated with female slaves. As Mary Boykin Chesnut explained in her diary, “Every lady tells you who is the father of all the Mulatto children in everybody’s household, but those in her own, she seems to think drop from the clouds or pretends to think so.” In 1850, when Catherine Hammond discovered James’s sexual relations with an enslaved mother and daughter, she moved to Charleston with her two youngest daughters. Most wives, however, stayed put, and some took out their anger and frustration on slave women already victimized by their husbands. Moreover, some mistresses owned slaves themselves, traded them on the slave market, and gave them as gifts or bequests to family members and friends.

Not all slaveholders were wealthy planters like the Hammonds, with fifty or more slaves and extensive landholdings. Far more planters in the 1830s and 1840s owned between twenty and fifty slaves, and an even larger number of farmers owned just three to six slaves. These small planters and farmers could not afford to emulate the lives of the largest slave owners. Still, as Hammond wrote a friend in 1847, “The planters here are essentially what the nobility are in other countries. They stand at the head of society & politics.”