Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 340

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 285

New Spirits Rising

Although enthusiasm for temperance and other reforms waned during the panic of 1837 and many churches lost members, the Second Great Awakening revived following the panic. Increasingly, however, evangelical ministers competed for souls with a variety of other religious groups. In the 1840s, diverse religious groups flourished, many of which supported good works and social reform. The Society of Friends, or Quakers, the first religious group to refuse fellowship to slaveholders, grew throughout the early and mid-nineteenth century. Having divided in 1827 and then again in 1848, the Society of Friends continued to grow. So, too, did its influence in reform movements as activists like Amy Post carried Quaker testimonies against alcohol, war, and slavery into the wider society. Unitarians also combined religious worship with social reform. Their primary difference from other Christians was their belief in a single unified higher spirit rather than the Trinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. First established in Boston in 1787, Unitarian societies spread across New England in the 1820s, emerging mainly out of Congregational churches. Opposed to evangelical revivalism, Unitarians nonetheless spread west and south in the 1830s and 1840s, attracting well-to-do merchants and manufacturers as well as small farmers, shopkeepers, and laborers. Dedicated to a rational approach to understanding the divine, Unitarian church members included prominent literary figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Harvard luminaries such as William Ellery Channing.

Other churches grew as a result of immigration. Dozens of Catholic churches were established to meet the needs of many Irish and some German immigrants. With the rapid increase in the number of Catholic churches, more Irish priests were ordained in the United States, and women’s religious orders also became increasingly Irish in the 1840s and 1850s. By 1860 the Irish numbered 1.6 million of the 2.2 million Catholics in the United States. Meanwhile synagogues, Hebrew schools, and Hebrew aid societies signaled the growing presence of Jews in the United States. They came chiefly from Germany, though Jews were far fewer in number than Catholics.

Entirely new religious groups also flourished in the 1840s. One of the most important was the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, or Mormons, founded by Joseph Smith. Smith claimed that he began to receive visions from God at age fifteen and was directed to dig up gold plates inscribed with instructions for redeeming the Lost Tribes of Israel. The Book of Mormon (1830), supposedly based on these inscriptions, granted spiritual authority to the unlearned and mercy to the needy while it castigated the pride and wealth of those who oppressed the humble and the poor. At the same time, Smith founded the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, which he led as the Prophet. Although seeking converts, the church did not admit African Americans to worship.

Smith founded not only a church but a theocracy (a community governed by religious leaders). In the mid-1830s, Mormons established a settlement at Nauvoo, Illinois, built homes and churches, and recruited followers from the eastern United States and from England. But after Smith received revelations sanctioning polygamy, local authorities arrested him and his brother, and a mob lynched them. Brigham Young, a successful missionary, took over as Prophet and in 1846 led 12,000 followers west, 5,000 of whom built a thriving theocracy near the Great Salt Lake, in what would become the Utah Territory in 1850.

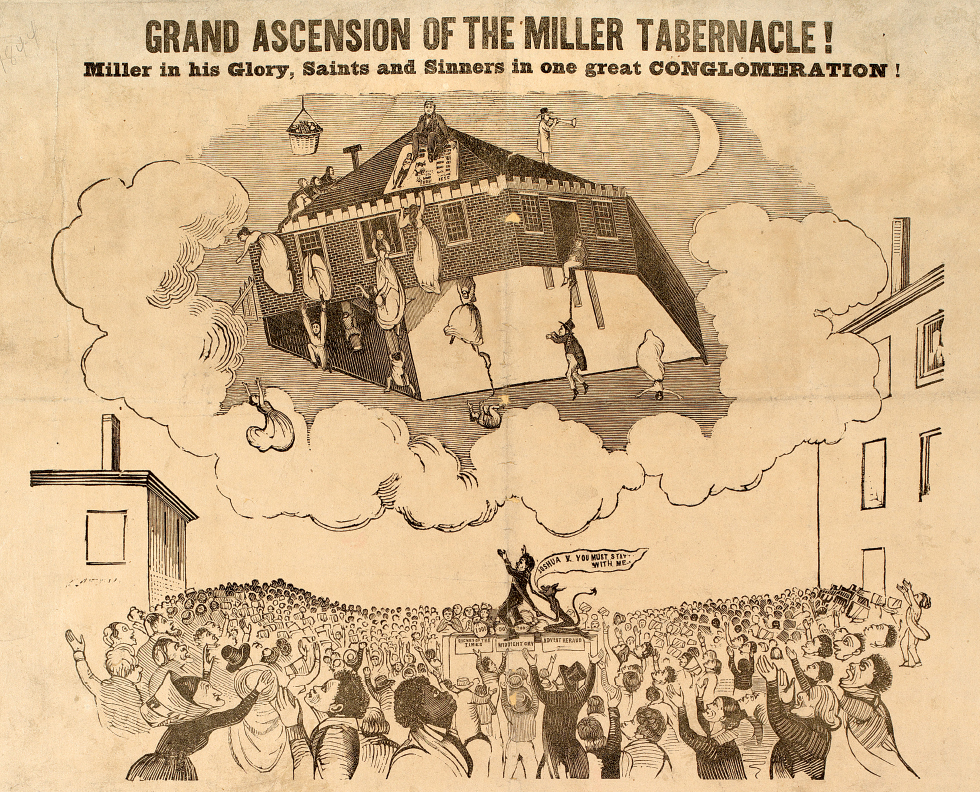

New religious groups also formed by separating from established denominations, just as Unitarians had split from Congregationalists. William Miller, a prosperous farmer and Baptist preacher, led one such movement. He claimed that the Bible proved that the Second Coming of Jesus Christ would occur in 1843. Thousands of Americans read Millerite pamphlets and newsletters and attended sermons by Millerite preachers. When various dates for Christ’s Second Coming passed without incident, however, Millerites developed competing interpretations for the failure and divided into distinct groups. The most influential group formed the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in the 1840s.