Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 327

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 272

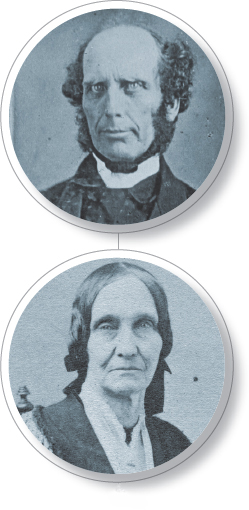

American Histories: Charles Grandison Finney and Amy Kirby Post

AMERICAN HISTORIES

Charles Grandison Finney, one of the greatest preachers of the nineteenth century, was born in 1792 and raised in rural New York State. As a young man, Finney studied the law. But in 1821, like many others of his generation, he experienced a powerful religious conversion. No longer interested in a legal career, he turned to the ministry instead.

After being ordained in the Presbyterian Church, Finney joined “New School” ministers who rejected the more conservative traditions of the Presbyterian Church and embraced a vigorous evangelicalism. In the early 1830s, while his wife, Lydia, remained at home with their growing family, the Reverend Finney traveled throughout New York State preaching about Christ’s place in a changing America. He held massive revivals in cities along the Erie Canal, most notably in Rochester, and then moved on to New York City. He achieved his greatest success in places experiencing rapid economic development and an influx of migrants and immigrants, where the clash of cultures and classes fueled fears of moral decay. Spiritual renewal could rescue the young nation from sin and depravity.

Finney urged Christians to actively seek salvation. Once individuals reformed themselves, he said, they should work to abolish poverty, intemperance, prostitution, and slavery. He expected women to participate in revivals and good works but advised them to balance these efforts with their domestic responsibilities, an ideal modeled by his own wife.

In many ways, Amy Kirby Post fit Finney’s ideal. She raised five children while devoting herself to spiritual and social reform. However, Amy Kirby was born into a large, close-knit Quaker family in the farming community of Jericho, New York. While most Quakers believed in quiet piety rather than evangelical revivals, their faith also provided solace in times of sorrow. In 1823, at age twenty-one, Amy became engaged to a fellow Quaker in central New York, where her sister Hannah lived with her husband, Isaac Post. But her fiancé died in June 1825 just before their wedding. Hannah took sick a year later, and Amy nursed her until her death in April 1827. She stayed on to care for Hannah’s two young children and two years later married Isaac Post.

Amy experienced these personal upheavals in the midst of heated religious controversies among Quakers. In the 1820s, Elias Hicks claimed that the Society of Friends had abandoned its spiritual roots and become too much like a traditional church. His followers, called Hicksites, insisted that Friends should reduce their dependence on disciplinary rules, elders, and preachers and rely instead on the “Inner Light”—the spirit of God dwelling within each individual. When the Society of Friends divided into Hicksite and Orthodox branches in 1827, Amy Kirby and Isaac Post joined the Hicksites.

In 1836 Amy Post moved with her husband and four children to Rochester, New York. In a city marked by the spirit of Finney’s revivals, Quakers emphasized quiet contemplation rather than fiery sermons and emotional conversions. But the Society of Friends allowed women to preach when moved by the spirit. Quaker women also held separate meetings to discipline female congregants, evaluate marriage proposals, and write testimonies on important religious issues.

Amy Post’s spiritual journey was increasingly shaped by the rising tide of abolition. Committed to ending slavery, she joined non-Quakers in signing an 1837 antislavery petition. Five years later, she helped found the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society, which included Quakers and evangelicals, women and men, and blacks and whites. Post’s growing commitment to abolition caused tensions in the Hicksite Meeting since some members opposed working in “worldly” organizations alongside non-Quakers. By 1848 Post and other radical Friends had withdrawn from the Hicksite Meeting and invited like-minded people to join them in the newly established Congregational Friends. Their meetings attracted abolitionists, advocates of Indian rights and women’s rights, and peace activists, all causes Post embraced. •

THE AMERICAN HISTORIES of Charles Finney and Amy Post were shaped by the dynamic religious, social, and economic developments in the early-nineteenth-century United States. Finney changed the face of American religion, aided by masses of evangelical Protestants. The rise of cities and the expansion of industry in the northern United States made problems like poverty, unemployment, alcohol abuse, crime, and prostitution more visible, drawing people to Finney’s message. Other Americans brought their own religious traditions to bear on the problems of the day. Some, like Post, were so outraged by the moral stain of slavery that they burst traditional religious bonds and reconsidered what it meant to do God’s work. For both Finney and Post, Rochester—the fastest-growing city in the nation between 1825 and 1835—exemplified the problems and the possibilities created by urban expansion and social change.