Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 331

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 277

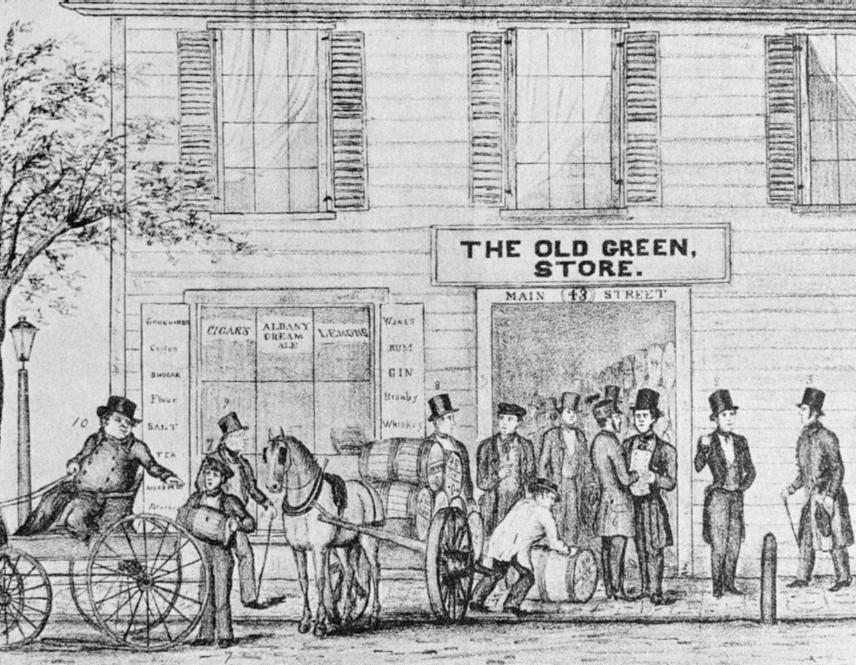

The New Middle Class

Members of the emerging middle class were among the most avid readers of the burgeoning numbers of newspapers and magazines. They included ambitious businessmen, successful shopkeepers, doctors, and lawyers as well as teachers, journalists, ministers, and other salaried employees. In Britain, the middle class emerged at the turn of the nineteenth century. In the United States, it was still a class in the making, rather than a stable entity, in the first half of the nineteenth century. At the top rungs, wealthy entrepreneurs and professionals adopted luxurious lifestyles. At the lower rungs, a growing cohort of salaried clerks and managers hoped that their hard work, honesty, and thrift would be rewarded with upward mobility.

Education, religious affiliation, and sobriety were important indicators of middle-class status. A well-read man who attended a well-established church and drank in strict moderation was marked as belonging to this new rank. A middle-class man was also expected to own a comfortable home, marry a pious woman, and raise well-behaved children. Entrance to the middle class required the efforts of wives as well as husbands, and so couples adopted new ideas about marriage and family. They believed that marital relationships should be based on affection and companionship rather than the husband’s supreme authority. As partners for life, the husband focused on achieving financial security while the wife managed the household. The French traveler Alexis de Tocqueville captured this development in Democracy in America (1835). “In no country,” he wrote, “has such constant care been taken . . . to trace two clearly distinct lines of action for the two sexes.” The millions of women who toiled on farms and plantations or as mill workers and domestic servants certainly challenged this notion of separate spheres for men and women, but it captured the middle-class ideal.

The rise of the middle class inspired a flood of advice books, ladies’ magazines, religious periodicals, and novels that advocated new ideals of womanhood, ideals that emphasized the centrality of child rearing and homemaking to women’s identities. This cult of domesticity seemed to restrict wives to home and hearth, where they provided their husbands with respite from the cares and corruptions of the world. But wives were also expected to cement social and economic bonds by visiting the wives of business associates, serving in local charitable societies, and attending prayer circles. In carrying out these duties, the ideal woman bolstered her family’s status by performing public as well as private roles.

Middle-class families also played a crucial role in the growing market economy. Although wives and daughters were not expected to work for wages, they were responsible for much of the family’s consumption. They purchased factory-produced shoes and cloth, handcrafted clocks and cast-iron stoves, fine European crystal, and porcelain figures imported from China. Some middling housewives also bought basic goods once made at home, such as butter and candles. And middle-class children required books, pianos, and dancing lessons.

Although increasingly recognized for their ability to consume wisely, middle-class women still performed significant domestic labor. Only upper-middle-class women could afford servants. Most middle-class women, aided by daughters or temporary “help,” cut and sewed garments, cultivated gardens, canned fruits and vegetables, plucked chickens, cooked meals, and washed and ironed clothes. As houses expanded in size and clothes became fancier, these chores continued to be laborious and time-consuming. But they were also increasingly invisible, focused inwardly on the family rather than outwardly as part of the market economy.

Middle-class men contributed to the consumer economy as well. Most directly, they created and invested in industrial and commercial ventures. But in carrying out their business and professional obligations, they supported new leisure pursuits. Many joined colleagues at restaurants, the theater, or sporting events. They also attended plays and lectures with their wives, visited museums, and took their children to the circus.

Review & Relate

|

Why did American cities become larger and more diverse in the first half of the nineteenth century? |

What values and beliefs did the emerging American middle class embrace? |