Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 368

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 307

The Fugitive Slave Act Inspires Northern Protest

The fugitive slave laws of 1793 and 1824 mandated that all states aid in apprehending and returning runaway slaves to their owners. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was different in two important respects. First, it eliminated jury trials for alleged fugitives. Second, the law required individual citizens, not just state officials, to help return runaways or else risk being fined or imprisoned. The act angered many Northerners who believed that the federal government had gone too far in protecting the rights of slaveholders and thereby aroused sympathy for the abolitionist cause.

Before 1850, the most well-known individuals aiding fugitives were free blacks such as David Ruggles in New York City; Jermaine Loguen in Syracuse, New York; and, after his own successful escape, Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York. Their main allies in this work were white Quakers such as Amy and Isaac Post in Rochester; Thomas Garrett in Chester County, Pennsylvania; and Levi and Catherine Coffin in Newport, Indiana. The work was dangerous. Charles Turner Torrey, a white Congregationalist minister, may have aided as many as four hundred fugitives, but he was eventually caught and imprisoned. He died of tuberculosis in a Baltimore jail in 1846.

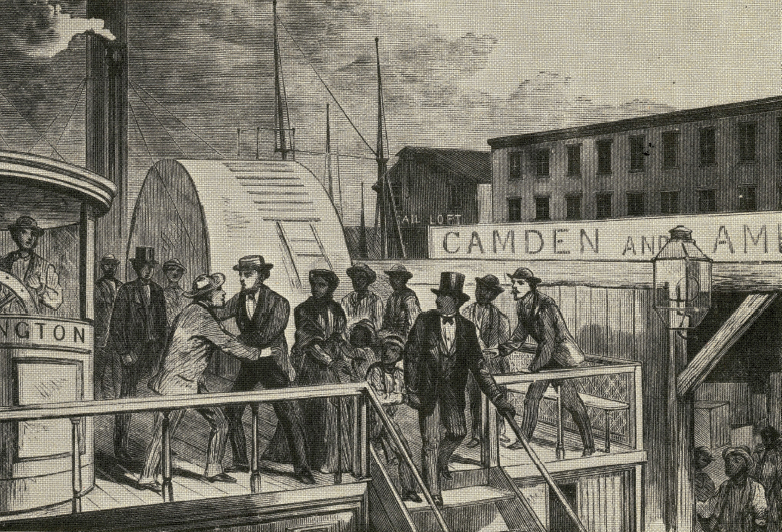

Following passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, the number of slave owners and hired slave catchers pursuing fugitives increased dramatically. But so, too, did the number of northern abolitionists helping blacks escape. Enslaved women and men followed various paths northward from rural plantations and southern cities. Once they crossed into free territory, most fugitives contacted free blacks or individuals known to be sympathetic to their cause. They then began the often slow progress along the underground railroad, from house to house or barn to barn, until they found safe haven. A small number of fortunate slaves were led north by fugitives like Harriet Tubman, who returned south repeatedly to free dozens of family members and other enslaved men and women. Fugitives followed disparate paths through the Midwest, Pennsylvania, New York, and New England, and there was little coordination among the “conductors” from one region or state to another. But the underground railroad was nonetheless an important resource for fugitives, some of whom sought refuge in Canada while others hoped to blend into free black communities in the United States.

Free blacks were endangered by the claim that slaves hid themselves in their midst. In Chester County, Pennsylvania, on the Maryland border, newspapers reported on at least a dozen free blacks who were kidnapped or arrested as runaways in the first three months of 1851. One provision of the Fugitive Slave Act encouraged such arrests: Commissioners were paid $10 for each slave sent back but only $5 if a slave was not returned. Without the right to a trial, a free black could easily be sent south as a fugitive. It was this fear that prompted hundreds of African Americans, both free and enslaved, to flee to Canada.

At the same time, a growing number of Northerners challenged the federal government’s right to enforce the law. Blacks and whites organized protest meetings throughout the free states. At a meeting in Boston in 1851, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison denounced the law: “We execrate it, we spit upon it, we trample it under our feet.” Abolitionists also joined forces to rescue fugitives who had been arrested. In Syracuse, New York, in October 1851, Jermaine Loguen, Samuel Ward, and the Reverend Samuel J. May led a well-organized crowd as it broke into a Syracuse courthouse to rescue a fugitive slave known as Jerry. They successfully hid him from authorities and then spirited him to Canada. As such incidents increased across the North, Daniel Webster bemoaned the lack of respect for federal law, and President Fillmore lamented the rise of “mob rule.” But northern abolitionists gained growing sympathy from their neighbors and became bolder in denouncing both the Fugitive Slave Act and “the bloodhound kidnappers” who sought to enforce it.

Meanwhile members of Congress continued to debate the law’s effects. Senator Frémont was among the legislators who helped defeat a bill that would have imposed harsher penalties on those who assisted runaways. And Congress felt growing pressure to calm the situation, including from foreign officials who were horrified by the violence required to sustain slavery in the United States. Abolitionist speakers like Frederick Douglass, who spent six months denouncing the Fugitive Slave Act across Canada, Ireland, and England, intensified foreign concern over the law. Great Britain and France had already abolished slavery in their West Indian colonies and found it hard to support what they saw as extreme policies to keep the institution alive in the United States. Yet neither southern slaveholders nor northern abolitionists were willing to compromise any further.