Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 372

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 311

The Kansas-Nebraska Act Stirs Dissent

Kansas provided the first test of the effects of Uncle Tom’s Cabin on northern sentiments toward slavery’s expansion. As white Americans slowly displaced Indian nations from their homelands, large and diverse groups of Indians settled in the northern half of the Louisiana Territory. This unorganized region had once been considered beyond the reach of white settlement, but Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois was eager to have a transcontinental railroad run through his home state. He needed the federal government to gain control of land along the route he proposed, and therefore he argued for the establishment of a vast Nebraska Territory. But to support his plan, Douglas also needed to convince southern congressmen, who sought a route through their own region. Much of the unorganized territory lay too far north to support plantation slavery, but a small portion lay directly west of Missouri, the northernmost slave state. According to the Missouri Compromise, states lying above the southern border of Missouri were automatically free. To gain southern support, Douglas sought to reopen the question of slavery in the territories. Pointing to the Compromise of 1850, by which territories acquired from Mexico would decide the fate of slavery by popular sovereignty, he argued that the same standard should apply to all new territories.

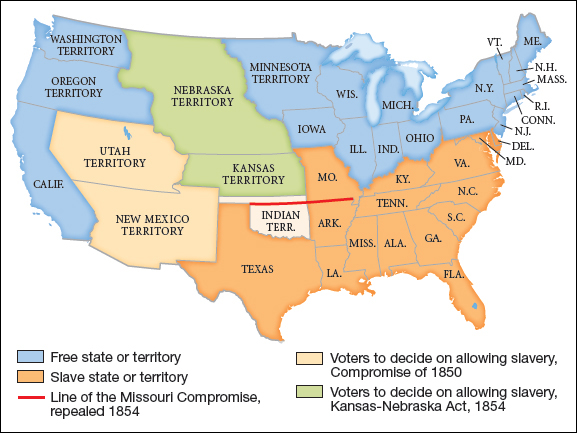

In January 1854, Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act to Congress. The act extinguished Indians’ long-held treaty rights in the region and repealed the Missouri Compromise. Two new territories—Kansas and Nebraska—would be carved out of the unorganized lands, and each would determine whether to enter the nation as a slave or a free state by a referendum of eligible voters (Map 12.2). The act spurred intense opposition from most Whigs and some northern Democrats who wanted to retain the Missouri Compromise line. Months of fierce debate followed. Finally, on May 25, Douglas’s proposed act passed by a comfortable majority when most Democrats followed the party line to vote yes. President Pierce quickly signed the bill into law.

Passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act enraged many Northerners, who considered the dismantling of the Missouri Compromise a sign of the rising power of the South. They were infuriated that the South—or what some now called the Slave Power Conspiracy—had once again benefited from northern politicians’ willingness to compromise. Although few of these opponents considered the impact of the law on Indians, the act also shattered treaty provisions that had protected the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Ponco, Pawnee, and Sioux nations. These Plains Indians lost half the land they had held by treaty as thousands of settlers swarmed into the newly organized territories. In the fall of 1855, conflicts between white settlers and Indians erupted across the southern and central plains. The U.S. army then sent six hundred troops to retaliate against a Sioux village, killing eighty-five residents of Blue Water in the Nebraska Territory and triggering continued violence throughout the region.

As tensions escalated across the nation, Americans faced the 1854 congressional elections. The Democrats, increasingly viewed as supporting the priorities of slaveholders, lost badly in the North. But the Whig Party also proved weak, having failed to stop the Slave Power from extending its leverage over federal policies. A third party, the American Party, was founded in the early 1850s and attracted native-born workers and Protestant farmers who were drawn to its anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic message. Responding to these political realignments, another new party—the Republicans—was founded in the spring of 1854. Led by antislavery Whigs, the Republican Party slowly attracted former Free-Soilers to its ranks. Among its early members was a Whig politician from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln.

Born in Kentucky in 1809, Lincoln moved north to Illinois with his family and worked as a farmhand and surveyor. He also taught himself the rudiments of the law and was elected to the state legislature in 1834. In 1842 he married Mary Todd, the daughter of a wealthy banker, and established a lucrative law practice. Four years later, Lincoln was elected as a Whig to the House of Representatives. Serving his two-year term during the crisis over war with Mexico, he challenged Polk’s claim that the first blood had been shed on U.S. soil. After resuming his Springfield law practice, Lincoln joined the new Republican Party in 1856.

Although established only months before the fall 1854 elections, the Republican Party gained significant support in the Midwest, particularly in state and local campaigns. Meanwhile the American Party gained control of the Massachusetts legislature and nearly captured New York as well. These victories marked the demise of the Whigs as a national party. Although the American Party dissolved as a political force by 1856, the Republicans continued to gain strength. They replaced the Whig Party—which was built on a national constituency—with a party rooted solely in the North. Like Free-Soilers, the Republicans argued that slavery should not be extended into new territories. But the Republicans also advocated a program of commercial and industrial development and internal improvements. With this platform, the party attracted a broader base than did earlier antislavery political coalitions. The Republican Party included both ardent abolitionists and men whose only concern was keeping western territories open to free white men. This latter group was more than willing to accept slavery where it already existed and to exclude black migrants, who might compete for jobs and land, from western states and territories. See e-Document Project 12: Sectional Politics and the Rise of the Republican Party.