Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 379

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 317

The Election of 1860

Brown’s hanging set the tone for the 1860 presidential campaign. The Republicans met in Chicago in May 1860 and made clear that they sought national prominence by distancing themselves from the more radical wing of the abolitionist movement. The party platform condemned John Brown along with southern “Border Ruffians” who initiated the violence in Kansas. The platform accepted slavery where it already existed, but continued to advocate its exclusion from western territories. Finally, the party platform argued forcefully for internal improvements and protective tariffs. On the third ballot, Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln as their candidate for president. Recognizing the impossibility of gaining significant votes in the South, the party focused instead on winning large majorities in the Northeast and Midwest.

The Democrats met in Charleston, South Carolina. Although Stephen Douglas was the leading candidate, he could not assuage southern delegates who were still angry that Kansas had been admitted as a free state. Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis then introduced a resolution to protect slavery in the territories, but Douglas’s northern supporters rejected it. When President Buchanan came out against Douglas, the Democratic convention ended without choosing a candidate. Instead, various factions held their own conventions. A group of largely northern Democrats met in Baltimore and nominated Douglas. Southern or “cotton” Democrats selected John Breckinridge, the current vice president and a Kentucky slaveholder, on a platform that included the extension of slavery and the annexation of Cuba. The Constitutional Union Party, comprised mainly of former southern Whigs, advocated “no political principle other than the Constitution of the country, the union of the states, and the enforcement of the laws.” Its members nominated Senator John Bell of Tennessee, a onetime Whig.

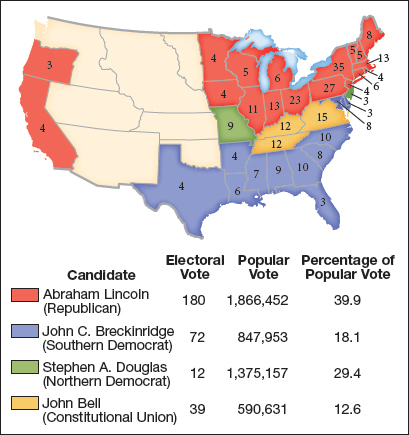

Although Lincoln won barely 40 percent of the popular vote, he carried a clear majority in the electoral college. With the admission of Minnesota and Oregon to the Union in 1858 and 1859, free states now outnumbered slave states eighteen to fifteen, and Lincoln won all but one of them. Moreover, free states in the Middle Atlantic and Midwest were among the most populous in the nation and therefore had a large number of electoral votes. Douglas ran second to Lincoln in the popular vote, but Bell and Breckinridge captured more electoral votes than Douglas did. Despite a deeply divided electorate, Lincoln became president (Map 12.3).

Although many abolitionists were wary of the Republicans’ position on slavery, especially their willingness to leave slavery alone where it already existed, most were nonetheless relieved at Lincoln’s victory and hoped he would become more sympathetic to their views once in office. Meanwhile, southern whites, especially those in the deep South, were furious that a Republican had won the White House without carrying a single southern state.