Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 363

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 300

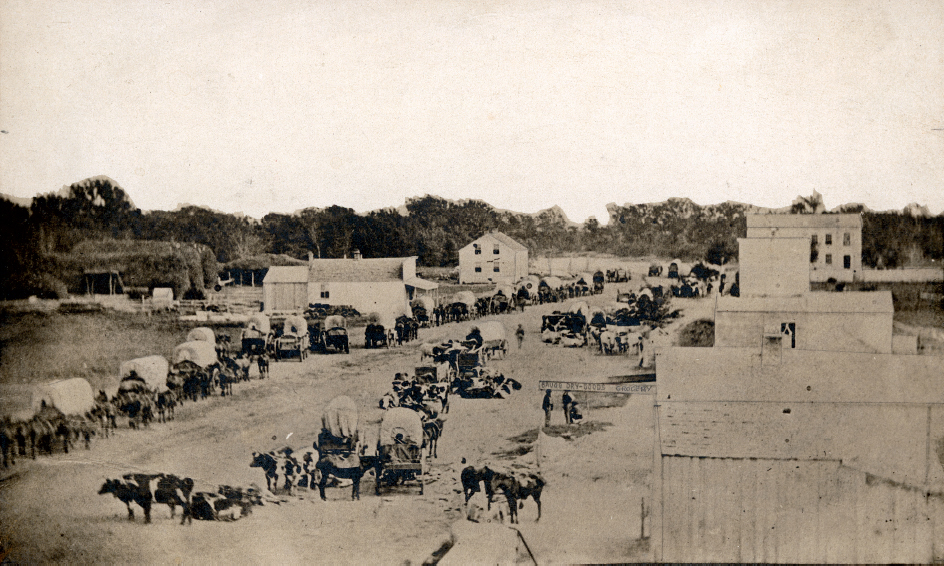

Traveling the Overland Trail

In the 1830s, a few white families had ventured to the western frontier. Some traveled around the southern tip of South America by ship or across the Isthmus of Panama by boat and mule train. But a growing number followed overland trails to the far West. In 1836 Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spaulding joined a group traveling to the Oregon Territory, the first white women to make the trip. They accompanied their husbands, both Presbyterian ministers, who hoped to convert the region’s Indians. Their letters to friends and associates back east described the rich lands and needy souls in the Walla Walla valley and encouraged further migration.

The panic of 1837 also prompted Americans to head west as thousands of U.S. migrants and European immigrants sought new opportunities in the 1840s. They were drawn to Oregon, the Rocky Mountain region, and the eastern plains. The Utah Territory, not yet officially part of the United States, attracted large numbers of Mormons. Some pioneers opened trading posts in the West where Indians exchanged goods with Anglo-American settlers or with merchants back east. Small settlements developed around these posts and near the expanding system of forts that dotted the region.

For many pioneers, the journey on the Oregon Trail began at St. Louis. From there, they traveled by wagon train across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific coast. By 1860 some 350,000 Americans had made the journey, claimed land from the Mississippi to the Pacific, and transformed the United States into an expanding empire.

Because the trip to the West required funds for wagons and supplies, most pioneers were of middling status. The three- to six-month journey was also physically demanding, and most pioneers traveled with family members to help share the labor and provide support, though men outnumbered women and children, comprising some 60 percent of western migrants.

Explore

See Document 12.1 for one account of the journey west.

Early in the journey, women and men generally followed their customary roles: Men hunted, fished, and drove the wagons, while women cooked, washed, and watched the children. But traditional roles often broke down on the trail, and even conventional domestic tasks posed novel problems. Women had to cook unfamiliar food over open fires in all kinds of weather and with only a handful of pots and utensils. They washed laundry in rivers or streams, and on the plains they had to haul water for cooking or cleaning from great distances. Wood, too, was scarce on the plains, and women and children gathered buffalo dung (called “chips”) for fuel. Men frequently had to gather food rather than hunt and fish, or they had to learn to catch strange (and sometimes dangerous) animals, such as jack rabbits and rattlesnakes. Few men were prepared for the arduous work of pulling wagons out of ditches or floating them across rivers with powerful currents. Nor were many of them expert in shoeing horses or fixing wagon wheels, tasks that were performed by skilled artisans at home.

Expectations changed dramatically when men took ill or died on the journey. Then wives drove the wagon, gathered or hunted for food, and learned to repair axles and other wagon parts. When large numbers of men were injured or ill, women might serve as scouts and guides or pick up guns to defend wagons under attack by Indians or wild animals. Yet despite the growing burdens on pioneer women, they gained little power over decision making. Moreover, the addition of men’s jobs to women’s responsibilities was rarely reciprocated. Few men cooked, did laundry, or cared for children on the trail. Single men generally paid women on the trail to perform such chores for them, and a husband who lost his wife on the journey generally relied on “neighbor” women as he would at home.

In one area, however, relative equality reigned. Men and women were equally susceptible to disease, injury, and death on the trail. Accidents, gunshot wounds, drowning, broken bones, and infections affected individuals on every wagon train. Some groups were struck as well by influenza, cholera, measles, mumps, or scarlet fever—all deadly in the early nineteenth century. In addition, about 20 percent of women on the overland trail became pregnant, which posed even greater dangers than at home given rough roads, a lack of water, the abundance of dirt, and the frequent absence of midwives and doctors. Some 20 percent of women lost children or spouses on the trip west, though most had little time to mourn. Wagon trains usually stopped only briefly to bury the dead, leaving a cross or a pile of stones to mark the grave, and then moved on. Overall, about one in ten to fifteen migrants died on the western journey, leaving some 65,000 graves along the trails west.