Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 366

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 303

A Crowded Land

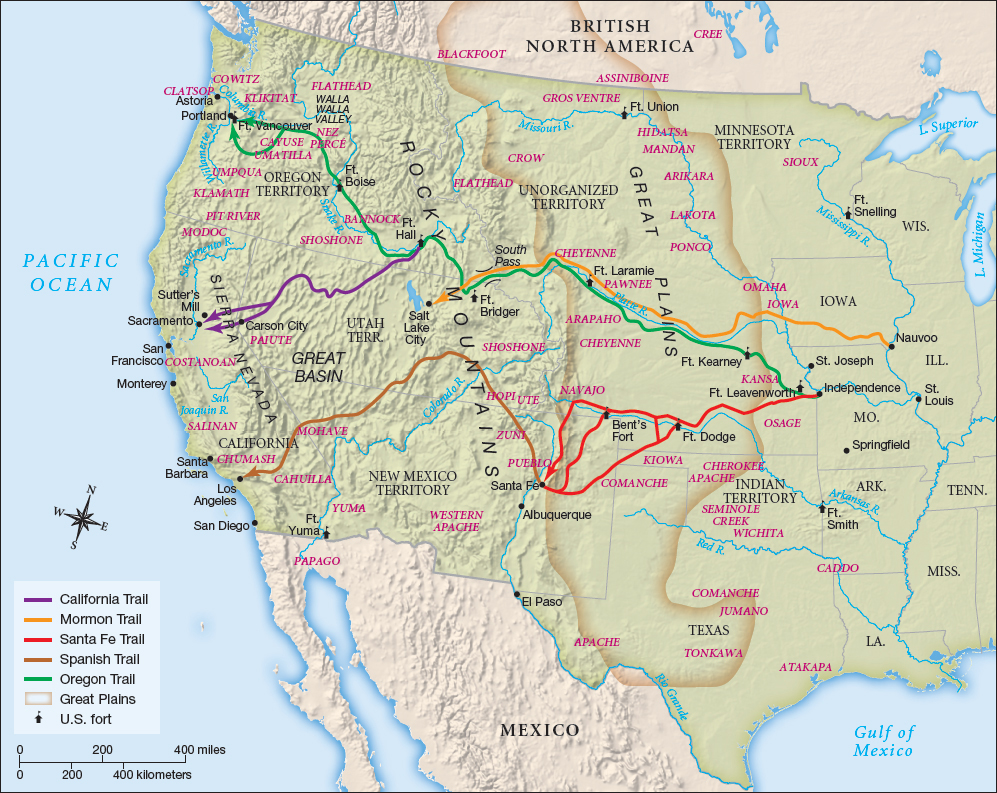

While U.S. promoters of migration continued to depict the West as an open territory waiting to be tamed and cultivated, it was in fact the site of competing imperial ambitions in the late 1840s. Despite granting statehood to Texas in 1845 and winning the war against Mexico in 1848, the United States had to compete with Comanche, Sioux, and other powerful Indian nations for control of the Great Plains (see chapter 10). As the U.S. government sought to secure land for railroads and forts and as American migrants and European immigrants carved out farms and villages, they had to contend with a range of Indian nations that refused to relinquish control (Map 12.1).

Although attacks on wagon trains were rare, Indians did threaten frontier settlements throughout the 1840s and 1850s. Settlers often retaliated, and U.S. army troops joined them in efforts to push Indians back from areas newly claimed by whites. Yet in many parts of the West, Indians were as powerful as whites, and they did not cede territory without a fight. For example, the Reverend Marcus Whitman and his wife Narcissa became victims of their success in promoting western settlement. In 1843 Marcus returned east and led one thousand Christian emigrants on a “Great Migration” to the Oregon Territory. The settlers were enthusiastic about their new homes, but the arrival of more whites proved disastrous for local Indians. The pioneers brought a deadly measles epidemic to the region, killing thousands of Cayuse and Nez Percé Indians. In 1847, convinced that whites brought disease but no useful medicine, a group of Cayuse Indians killed the Whitmans and ten other white settlers.

Yet violence against whites could not stop the flood of migrants into the Oregon Territory. Indeed, attacks by one Indian tribe were often used to justify assaults on any Indian tribe. For example, John Frémont and Kit Carson, whose party had been attacked by a group of Modoc Indians in Oregon in 1846, took their revenge by destroying a Klamath Indian village and killing men, women, and children there. The defeat of Mexico and the discovery of gold in California in 1848 only intensified these conflicts.

Although Indians and white Americans were the main players in many battles, Indian nations also competed with each other. In the southern plains, drought and disease exacerbated those conflicts in the late 1840s and dramatically changed the balance of power in the region. In 1845 the southern plains were struck by a dry spell, which lasted on and off until the mid-1860s. Three years later, smallpox ravaged Comanche villages, and then forty-niners heading to California introduced a virulent strain of cholera that killed prominent Comanche leaders as well as hundreds of their followers. In the late 1840s, the Comanches were the largest Indian nation, with about twenty thousand members; by the mid-1850s, less than half that number remained.

Yet the collapse of the Comanche empire was not simply the result of outside forces. As the Comanches expanded their trade networks and incorporated smaller Indian nations into their orbit, they overextended their reach. Most important, they allowed too many bison to be killed in order to meet the needs of their Indian allies and the demand for bison robes by Anglo-American and European traders. The Comanches also herded growing numbers of horses, which required expansive grazing lands and winter havens in the river valleys and pushed the bison onto more marginal lands. Opening up the Santa Fe Trail to commerce multiplied the problems by destroying vegetation, polluting springs, and thus damaging some of the last refuges for bison. The prolonged drought then completed the depopulation of the bison on the southern plains. Without bison, the Comanches lost one of their most critical trade items; by the late 1850s, they were left without the goods or leverage to sustain their commercial and political networks. As the Comanche empire collapsed, former Indian allies sought to advance their own interests. These two developments reignited Indian wars on the southern plains as tens of thousands of Anglo-Americans and European immigrants poured through the region.

African Americans also participated in these western struggles. Many were held as slaves by southeastern tribes forced into Indian Territory, while others were freed and married Seminole or Cherokee spouses. The Creeks proved harsh masters, prompting some slaves to escape north to free states or south to Mexican or Comanche territory. Yet as southern officers in the U.S. army moved to frontier outposts to secure American dominance, they carried more slaves into the region. Many, including Dr. Emerson, changed posts frequently, taking slaves like Dred Scott into western territories that were alternately slave and free. Still, it was white planters who brought the greatest numbers of African Americans into Texas, Missouri, and Kansas, pushing the frontier of slavery ever westward. At the same time, some free blacks joined the migration voluntarily in hopes of finding better economic opportunities and less overt racism on the frontier.

Review & Relate

|

Why did Americans go west in the 1830s and 1840s, and what was the journey like? |

What groups competed for land and resources in the West? How did competition lead to violence? |