Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 403

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 333

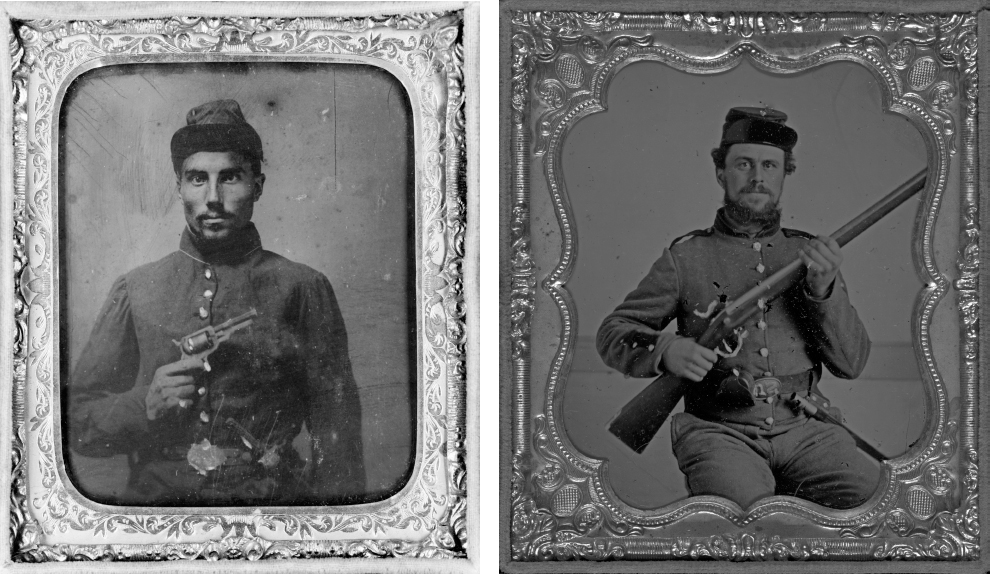

Life and Death on the Battlefield

Few soldiers entered the conflict knowing what to expect. A young private wrote home that his idea of combat had been that the soldiers “would all be in line, all standing in a nice level field fighting, a number of ladies taking care of the wounded, etc., etc., but it isn’t so.” See Document Project 13: Civil War Letters. Even where traditional forms of engagement did occur, improved weaponry turned them into scenes of carnage. Although individual soldiers could fire only a few times a minute, their Enfield and Springfield rifles were murderously effective at a quarter-mile distance. New conical bullets that expanded to fit the grooves of rifles proved far more accurate and more deadly than older round bullets. Minié balls that exploded on impact also increased fatalities. By mid-1863, the rival armies relied on heavy fortifications, elaborate trenches, and distant mortar and artillery fire when they could, but the casualties continued to rise, especially since the trenches proved to be a breeding ground for disease.

The hardships and discomforts of war extended beyond combat itself. As General Lee complained before the fighting at Antietam, many soldiers went into battle in ragged uniforms and without shoes. In the First Battle of Bull Run, a Georgia major reported that more than one hundred of his men were barefoot, “many of whom left bloody foot-prints among the thorns and briars through which they rushed.” Rations, too, ran short. Food was dispensed sporadically and was often spoiled. Many Union troops survived primarily on an unleavened biscuit called hardtack as well as small amounts of meat and beans and enormous quantities of coffee. At least their diet improved over the course of the war as the Union supply system grew more efficient. Confederate troops, however, subsisted increasingly on cornmeal and fatty meat. As early as 1862, Confederate soldiers were gathering food from the haversacks of Union dead.

“There is more dies by sickness than gets killed,” a recruit from New York complained in 1861. Indeed, for every soldier who died as a result of combat, three died of disease. Measles, dysentery, typhoid, and malaria killed thousands who drank contaminated water, ate tainted food, and were exposed to the elements. Prisoner-of-war camps were especially deadly locales. Debilitating fevers in a camp near Danville, Virginia, spread to the town, killing civilians as well as soldiers. In the fall of 1862, yellow fever and malaria killed nearly five hundred in Wilmington, Delaware, as infected soldiers built fortifications along the beaches.

African American troops fared worst of all. The death rate from disease for black Union soldiers was nearly three times greater than that for white Union soldiers, reflecting their generally poorer health upon enlistment, the hard labor they performed, and the minimal medical care they received in the field. Those who began their army careers in contraband camps fared even worse, with a camp near Nashville losing a quarter of its residents to death in just three months in 1864.

Even for white soldiers, medical assistance was primitive. Antibiotics did not exist, antiseptics were still unknown, and a perennial shortage of anesthetics meant that amputations were frequently conducted without it. Union soldiers did gain some access to better medical care from the U.S. Sanitary Commission, which was established by the federal government in June 1861 to improve and coordinate the medical care of Union soldiers. Nonetheless, a commentator accurately described most field hospitals as “dirty dens of butchery and horror.”

The need to bury the dead after battle was also a gruesome task. Early in the war, officers and enlisted men tried to recover and bury individual remains, but this practice proved unfeasible given the vast numbers killed. Instead, mass graves provided the final resting place for many soldiers on both sides. As the horrors of battle sank in and enlisted men discovered the inadequacies of food, sanitation, and medical care, large numbers of soldiers deserted. As the number of volunteers declined and the number of deserters rose, both the Confederate and the Union governments were eventually forced to institute conscription laws to draft men into service.

Explore

See Document 13.4 for an example of how photography brought the horrors of war home to civilians.