Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 392

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 323

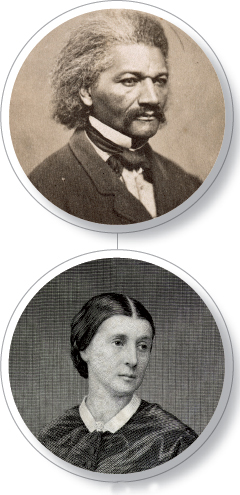

American Histories: Frederick Douglass and Rose O’Neal Greenhow

AMERICAN HISTORIES

Though born into slavery in 1818, by 1860 Frederick Douglass had become a celebrated orator, editor, and abolitionist. He ensured his fame in 1845 with publication of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. In it, he described his experiences of slavery in Maryland, his defiance against his masters, and his eventual escape to New York in September 1838 with the help of Anna Murray, a free black servant.

Frederick and Anna married in New York and then moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, and changed their last name to Douglass to avoid capture. But in 1841 Frederick began lecturing for the American Anti-Slavery Society, offering stirring accounts of his enslavement and escape. By publishing his Narrative four years later, Douglass made his capture even more likely, so in August 1845 he left for England, where wildly enthusiastic audiences attended his lectures and supporters raised funds to purchase his freedom. Douglass returned to Massachusetts in 1847, a truly free man.

A year later, Frederick moved to Rochester, New York, with Anna and their five children to launch his abolitionist paper, the North Star. Over the next decade, he became the most famous black abolitionist in the United States and an outspoken advocate of women’s rights. He also broke with the Garrisonian branch of abolitionists by joining the Liberty Party and later the Free-Soil and Republican parties. He was thus well placed when war erupted in April 1861 to lobby President Lincoln to make emancipation a war aim and enlist African Americans in the Union army.

Douglass embraced electoral politics and the use of military force to end slavery. His greatest fear was that Lincoln was more committed to reconstituting the Union than to abolishing slavery. But after the president issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, Douglass spoke enthusiastically on its behalf. At the same time, he continued to believe that military service was essential for black men to demonstrate their patriotism. His stirring editorial “Men of Color, to Arms” was turned into a recruiting poster, and he urged his own sons to join the Massachusetts Fifty-fourth Colored Infantry, one of the first African American regiments. But Douglass also protested discrimination against black troops and lobbied for federal protections of black civil rights.

Like Douglass, Rose O’Neal was born on a Maryland plantation, but she was white and free. Her father was likely John O’Neal, a planter who was slain by a slave in 1817, when Rose was four years old. In early adolescence, she moved to Washington, D.C., with her older sister. They lived with an aunt who ran a fashionable boardinghouse near Capitol Hill. The boarders included John C. Calhoun, whose states’ rights views Rose eagerly embraced. Intrigued by the lively political debates that marked the Jacksonian era, she was also schooled in the social graces. Charming and beautiful, Rose was welcomed into elite social circles, including invitations from Dolley Madison. In 1835 she married Robert Greenhow, a cultivated Virginian who worked for the State Department.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow quickly became a favorite Washington hostess. Like Dolley Madison, she entertained congressmen, cabinet ministers, and foreign diplomats with a wide range of views. In the midst of this social and political whirl, Rose gave birth to four daughters. Yet she also remained deeply invested in her husband’s career. She assisted Robert in the 1840s as he researched U.S. land claims in the Pacific Northwest. Ardent proslavery expansionists, the Greenhows supported efforts to acquire Cuba, and in 1850 they traveled to Mexico City to study California land claims. When Robert died in 1854, Rose moved into a smaller house in Washington but continued to entertain political leaders and sustained friendships with powerful men like President James Buchanan.

In May 1861, just as the Civil War commenced, a U.S. army captain about to join the Confederate cause recruited Greenhow to head an espionage ring in Washington, D.C. With her close ties to southern sympathizers working in government offices and her extensive social network, Greenhow gathered important intelligence on Union political and military plans. Although she initially avoided suspicion, by August Greenhow was investigated and placed under house arrest. When she continued to smuggle out letters, embarrassing Union officials, she was sent to the Old Capitol Prison in January 1862. Once again, Greenhow managed to transmit information and riled up the other prisoners. In June, she was exiled to Richmond, where Confederate president Jefferson Davis hailed her as a hero and awarded her $2,500. •

THE AMERICAN HISTORIES of Frederick Douglass and Rose O’Neal Greenhow were shaped by the sectional conflict over slavery that culminated in the Civil War. Both were born on Maryland plantations, one as a slave and the other a daughter of slave owners. Both honed their innate talents, one as an orator and a writer, the other as a hostess and gatherer of intelligence. And both embraced the Civil War as the last best hope for national salvation, one on the side of union and emancipation, the other on the side of secession and slavery. They were among hundreds of thousands of Americans—men and women, black and white, North and South—who saw the war as a means to achieve their goals: a free nation, a haven for slavery, or a reunited country.