Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 396

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 327

Both Sides Prepare for War

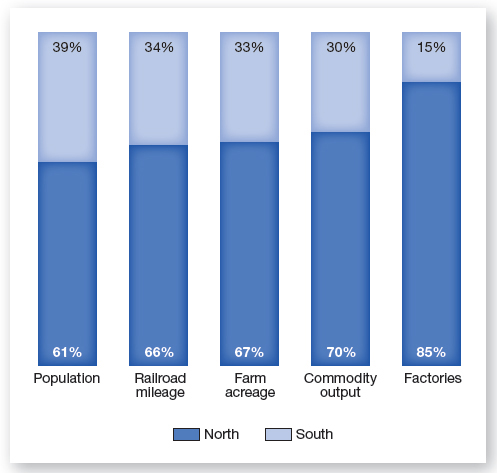

At the onset of the war, the Union held a decided advantage in resources and population. The Union states held more than 60 percent of the U.S. population, while the Confederate states held less than 40 percent. And the Confederacy included several million slaves who would not be armed for combat. The Union also outstripped the Confederacy in manufacturing and even led the South in agricultural production. The North’s many miles of railroad track ensured greater ease in moving troops and supplies. And the Union could launch far more ships to blockade southern ports (Figure 13.1).

Yet Union forces were less prepared for war than were the Confederates, who had been organizing troops and gathering munitions for months. To match their efforts, Winfield Scott, general in chief of the U.S. army, told Lincoln he would need at least 300,000 men committed to serve for two or three years. But the president, who feared unnerving Northerners, asked for only 75,000 volunteers for three months. Recruits poured into state militias, and thousands more offered their services directly to the federal government. Yet rather than forming a powerful national army led by seasoned officers, Lincoln left recruitment, organization, and training largely to the states. The result was disorganization and the appointment of new officers based more on political connections than on military expertise.

Confederate leaders also initially relied on state militia units and volunteers, but they prepared for a prolonged war from the start. Before the firing on Fort Sumter, President Davis signed up 100,000 volunteers for a year’s service. The labor provided by slaves allowed a large proportion of white working-age men to volunteer for military service. And Southerners knew they were likely to be fighting mainly on home territory, where they had expert knowledge of the terrain. When the final four states joined the Confederacy, the southern army also gained important military leadership. It ultimately recruited 280 West Point graduates, including Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, James Longstreet, and others who had proved their mettle in the Mexican-American War.

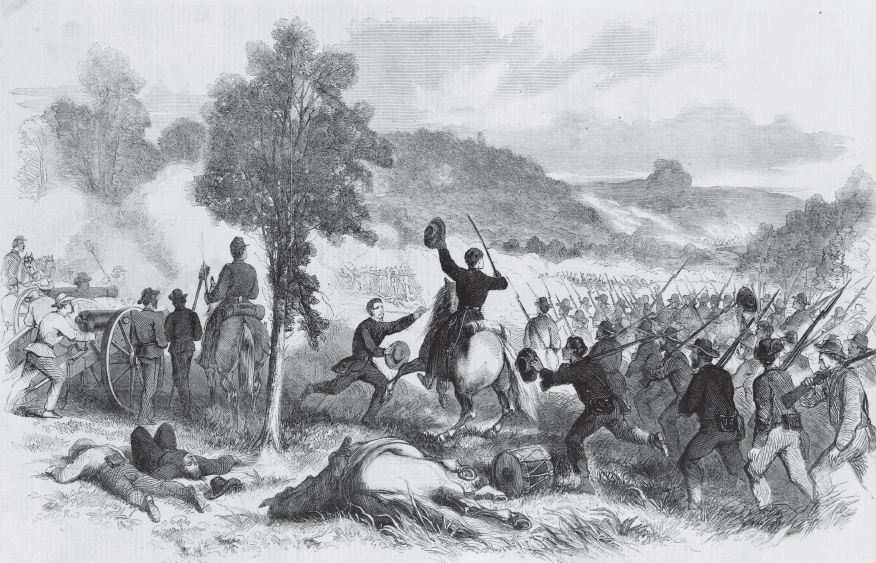

The South’s advantages were apparent in the first major battle of the war. But Confederate troops were also aided by information on Union plans sent by Rose Greenhow. Confederate forces were thus well prepared when 30,000 Union troops marched on northern Virginia on July 21, 1861. At the Battle of Bull Run (or Manassas), 22,000 Confederates repelled the Union attack. During the fighting, 800 men lost their lives, giving Americans their first taste of the carnage that lay ahead. Civilians from Washington who traveled to the battle site to view the combat had to flee for their lives to escape Confederate artillery.

Despite Union defeats at Bull Run and Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, in August 1861, the Confederate army did not follow up with major strikes against Union forces. Meanwhile the Union navy began blockading the South’s deepwater ports. When the armies settled into winter camps in 1861–1862, both sides recognized that the war was likely to be a long struggle demanding a far greater commitment of men and resources than anyone had imagined just months earlier.

Review & Relate

|

What steps did Lincoln take to prevent war? Why were they ineffective? |

What advantages and disadvantages did each side have at the onset of the war? |