Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 427

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 352

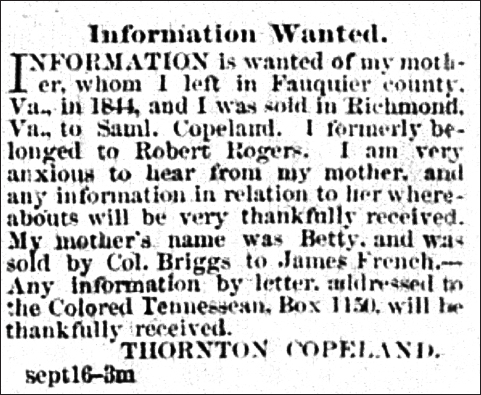

Reuniting Families Torn Apart by Slavery

The first priority for many newly freed blacks was to reunite families torn apart by slavery. Men and women traveled across the South to find spouses, children, parents, siblings, aunts, and uncles. Well into the 1870s and 1880s, parents ran advertisements in newly established black newspapers, providing what information they knew about their children’s whereabouts and asking for assistance in finding them. They sought help in their quests from government officials, ministers, and other African Americans. Milly Johnson wrote to the Freedmen’s Bureau in March 1867, after failing to locate the five children she had lost under slavery. In the end, she was able to locate three of her children, but any chance of discovering the whereabouts of the other two was lost when the records of the slave trader who purchased them burned during the war. Although such difficulties were common, thousands of slave children were reunited with their parents in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Husbands and wives, or those who considered themselves as such despite the absence of legal marriage under slavery, also searched for each other. Those who lived on nearby plantations could now live together for the first time. Those whose husband or wife had been sold to distant plantation owners had a more difficult time. They wrote (or had letters written on their behalf) to relatives and friends who had been sold with their mate; sought assistance from government officials, churches, and even their former masters; and traveled to areas where they thought their spouse might reside.

Many such searches were complicated by long years of separation and the lack of any legal standing for slave marriages. In 1866 Philip Grey, a Virginia freedman, located his wife, Willie Ann, and their daughter Maria, who had been sold away to Kentucky years before. Willie Ann was eager to reunite with her husband, but in the years since being sold, she had remarried and borne three children. Her second husband had joined the Union army and was killed in battle. When Willie Ann wrote to Philip in April 1866, explaining her new circumstances, she concluded: “If you love me you will love my children and you will have to promise me that you will provide for them all as well as if they were your own. . . . I know that I have lived with you and loved you then and love you still.” Other spouses finally located their partner, only to discover that the husband or wife was happily married to someone else and refused to acknowledge the earlier relationship.

Despite these complications, most former slaves who found their spouse sought to legalize their relationship. Ministers, army chaplains, Freedmen’s Bureau agents, and teachers were flooded with requests to perform marriage ceremonies. In one case, a Superintendent for Marriages for the Freedmen’s Bureau in northern Virginia reported that he gave out seventy-nine marriage certificates on a single day in May 1866. In another, four couples went right from the fields to a local schoolhouse, still dressed in their work clothes, where the parson married them.

Of course, some former slaves hoped that freedom would allow them to leave an unhappy relationship. Having never been married under the law, couples could simply separate and move on. Complications arose, however, if they had children. In Lake City, Florida, in 1866, a Freedmen’s Bureau agent asked for advice from his superiors on how to deal with Madison Day and Maria Richards. They refused to legalize the relationship forced on them under slavery, but both sought custody of their three children, the oldest only six years old. As with white couples in the mid-nineteenth century, the father eventually was granted custody on the assumption that he had the best chance of providing for the family financially.