Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 428

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 353

Free to Learn

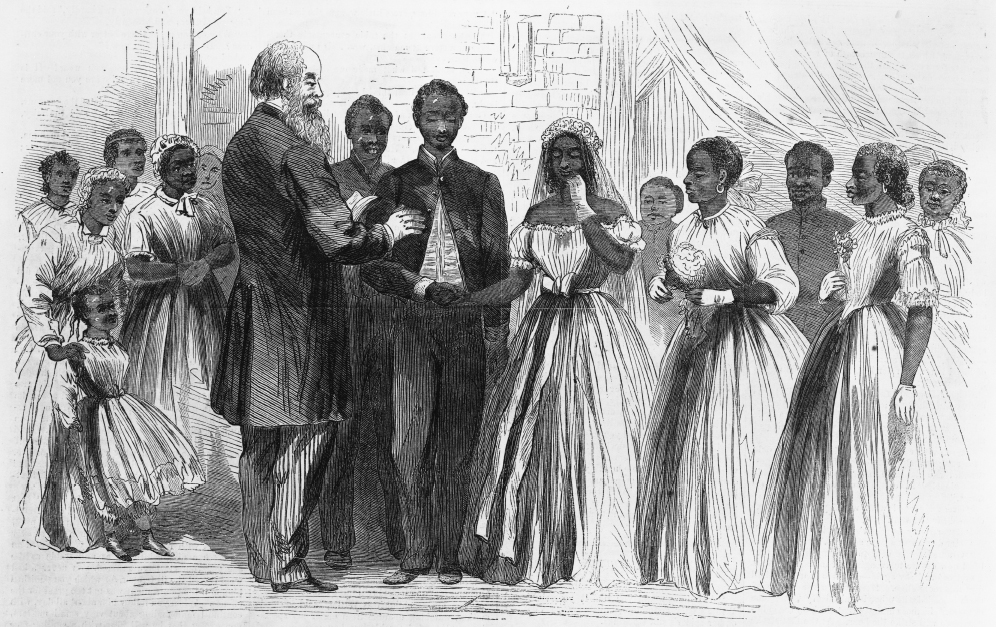

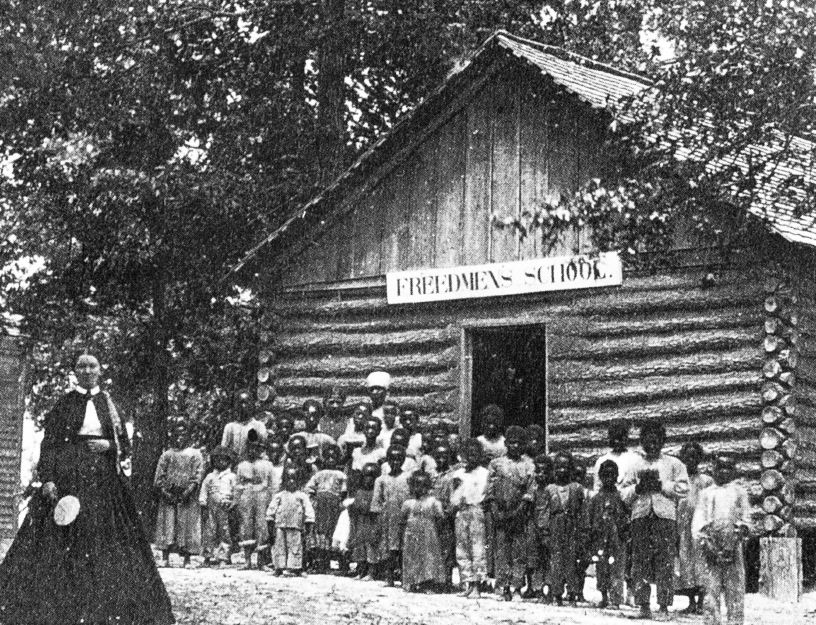

Reuniting families was only one of the many ways that southern blacks proclaimed their freedom. Learning to read and write was another. The desire to learn was all but universal. Writing of freedpeople during Reconstruction, Booker T. Washington, an educator and a former slave, noted, “It was a whole race trying to go to school. Few were too young, and none too old, to make the attempt to learn.” A newly liberated father in Mississippi proclaimed, “If I nebber does nothing more while I live, I shall give my children a chance to go to school, for I considers education [the] next best ting to liberty.”

A variety of organizations opened schools for former slaves during the 1860s and 1870s. By 1870 nearly a quarter million blacks were attending one of the 4,300 schools established by the Freedmen’s Bureau. Black and white churches and missionary societies also launched schools. Even before the war ended, the American Missionary Association called on its northern members to take the freedpeople “by the hand, to guide, counsel and instruct them in their new life.” This and similar organizations sent hundreds of teachers, black and white, women and men, into the South to open schools in former plantation areas. Their attitudes were often paternalistic and the schools were segregated, but the institutions they established offered important educational resources for African Americans.

The demand for education was so great that almost any kind of building was pressed into service as a schoolhouse. A mule stable in Helena, Arkansas; a billiard room on the Sea Islands; a courthouse in Lawrence, Kansas; and a former cotton shed on a St. Simon Island plantation all attracted eager students. In New Orleans, local blacks converted a former slave pen into a school and named it after the famous activist, orator, and ex-slave Frederick Douglass.

Parents worked hard to keep their children in school during the day. Children, as they gained the rudiments of education, passed on their knowledge to mothers, fathers, and older siblings whose work responsibilities prevented them from attending school. Still, many freedpeople, having worked all day in fields, homes, or shops, then walked long distances in order to get a bit of education for themselves. In New Bern, North Carolina, where many blacks labored until eight o’clock at night, a teacher reported that they still insisted on spending at least an hour “in earnest application to study.”

Freedmen and freedwomen sought education for a variety of reasons. Some, like the Mississippi father noted above, viewed it as a sign of liberation. Others knew that they must be able to read the labor contracts they signed if they were ever to be free of exploitation by whites. Some men and women were eager to correspond with relatives far away, others to read the Bible. Growing numbers hoped to participate in politics, particularly the public meetings organized by freedpeople in cities across the South following the end of the war. These gatherings met to set an agenda for the future, and nearly everyone demanded that state legislatures immediately establish public schools for African Americans. Most black delegates agreed with A. H. Ransier of South Carolina, who proclaimed that “in proportion to the education of the people so is their progress in civilization.”

Despite the enthusiasm of blacks and the efforts of the federal government and private agencies, schooling remained severely limited throughout the South. A shortage of teachers and of funding kept enrollments low among blacks and whites alike. The isolation of black farm fam-ilies and the difficulties in eking out a living limited the resources available for education. Only about a quarter of African Americans were literate by 1880.