Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 479

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 397

The Chinese in the Far West

California and the far West also attracted a large number of Chinese immigrants. Migration to California and the West Coast was part of a larger movement in the nineteenth century out of Asia that brought impoverished Chinese to Australia, Hawaii, Latin America, and the United States. The Chinese migrated for several reasons in the decades after 1840. Internal conflicts in China sent them in search of refuge. Economic dislocation related to the British Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860), along with bloody family feuds and a decade of peasant rebellion from 1854 to 1864, propelled migration. Faced with unemployment and starvation, the Chinese sought economic opportunity overseas. One man recounted the hardships that drove him to emigrate: “Sometimes we went hungry for days. My mother and [I] would go over the harvested rice fields of the peasants to pick the grains they dropped. . . . We had only salt and water to eat with the rice.”

Chinese immigrants were attracted first by the 1848 gold rush and then by jobs building the transcontinental railroad. By 1880 the Chinese population had grown to 200,000, most of whom lived in the West. San Francisco became the center of the transplanted Chinese population, which congregated in the city’s Chinatown. Under the leadership of a handful of businessmen, Chinese residents found jobs, lodging, meals, and social, cultural, and recreational outlets. Most of those who came were young unmarried men who intended to earn enough money to return to China and start anew. The relatively few women who immigrated came as servants or prostitutes.

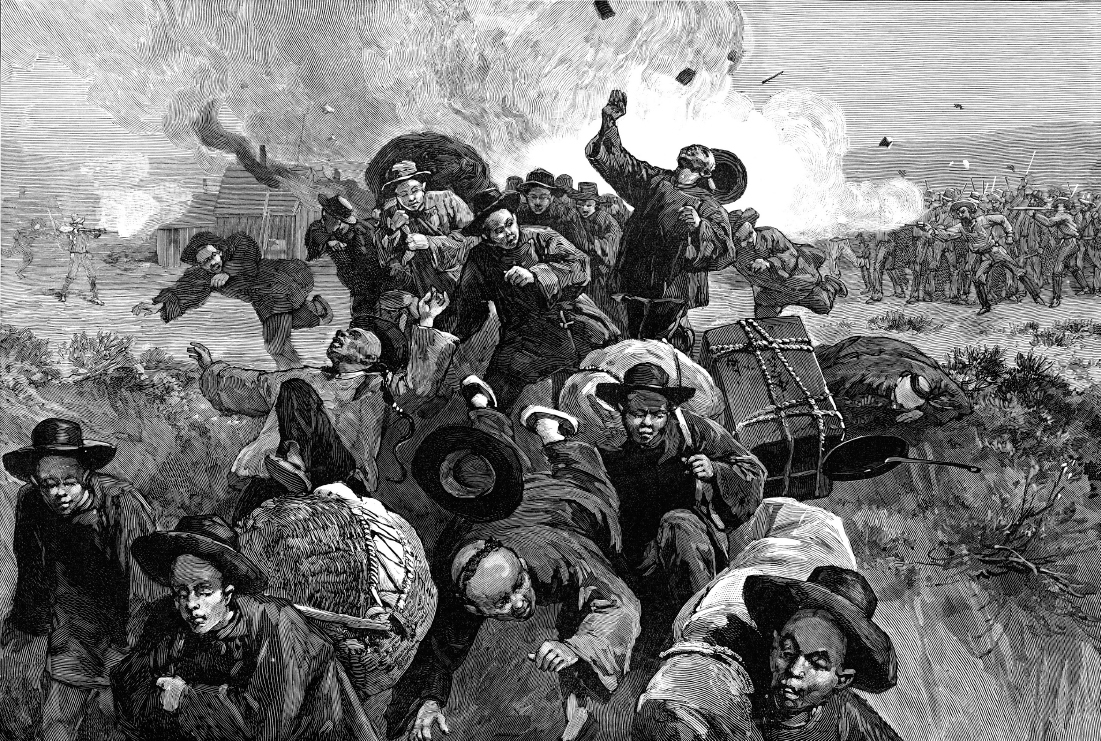

For many Chinese, the West proved unwelcoming. When California’s economy slumped in the mid-1870s, many whites looked to the Chinese as scapegoats. White workingmen believed that the plentiful supply of Chinese laborers in the mines and railroads undercut their demands for higher wages. They contended that Chinese would work for less because they were racially inferior people who lived degraded lives. Anti-Chinese clubs mushroomed in California during the 1870s, and they soon became a substantial political force in the state. The Workingmen’s Party advocated laws that restricted Chinese labor, and it initiated boycotts of goods made by Chinese people. Vigilantes attacked Chinese in the streets and set fire to factories that employed Asians. The Workingmen’s Party and the Democratic Party joined forces in 1879 to craft a new state constitution that blatantly discriminated against Chinese residents. In many ways, these laws resembled the Jim Crow laws passed in the South that deprived African Americans of their freedom following Reconstruction (discussed in chapter 16).

Pressured by anti-Chinese sentiment on the West Coast, the U.S. government enacted drastic legislation to prevent any further influx of Chinese. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banned Chinese immigration into the United States and prohibited those Chinese already in the country from becoming naturalized American citizens. As a result, the Chinese remained a predominantly male, aging, and isolated population until World War II. The exclusion act, however, did not stop anti-Chinese assaults. In the mid-1880s, white mobs drove Chinese out of Eureka, California; Seattle and Tacoma, Washington; and Rock Springs, Wyoming.

Review & Relate

|

What migrant groups were attracted to the far West? What drew them there? |

Explain the rising hostility to the Chinese and other minority groups in the late-nineteenth-century far West. |