Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 493

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 402

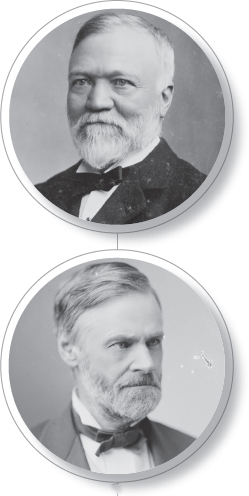

American Histories: Andrew Carnegie and John Sherman

AMERICAN HISTORIES

In 1848 Will and Margaret Carnegie left Scotland and sailed to America, hoping to find a better life for themselves and their two children. Once settled in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the family went to work, including thirteen-year-old Andrew, who found a job in a textile mill. For $1.25 per week, he dipped spools into an oil bath and fired the factory furnace—tasks that left him nauseated by the smell of oil and frightened by the boiler. Nevertheless, like the hero of the rags-to-riches stories that were so popular in his era, Andrew Carnegie persevered, rising from poverty to great wealth through a series of jobs and clever investments. As a teenager, he worked as a messenger in a telegraph office and was soon promoted to telegraph operator. A superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company noticed Andrew’s aptitude and made him his personal assistant and telegrapher. While in this position, Carnegie learned about the fast-developing railroad industry and purchased stock in a sleeping car company; the returns from that investment tripled his annual salary. Carnegie then became a railroad superintendent in western Pennsylvania, and by the time he was thirty-five, he had earned handsome returns on his investments in various industrial companies, as well as from oil investments he made just as that industry was emerging.

Andrew Carnegie eventually founded the greatest steel company in the world and became one of the wealthiest men of his time. In an era before personal and corporate income taxes, Carnegie earned hundreds of millions of dollars. He also became one of the era’s greatest philanthropists, fulfilling his sense of community obligation by giving away a great deal of his fortune.

John Sherman also believed in public service, but for him it would come through politics. Sherman was born in Lancaster, Ohio, in 1823, a quarter of a century before the Carnegies set sail for the United States. Sherman became a lawyer like his father, an Ohio Supreme Court judge, and in 1844 he set up a practice with his older brother, William Tecumseh Sherman, the future Civil War general and Indian fighter. Like Carnegie, Sherman made shrewd investments that made him a wealthy man, although not on the same scale as Carnegie.

Sherman decided to enter politics and in 1854 won election from Ohio to the House of Representatives as a member of the newly created Republican Party. He rose up the leadership ranks as Republicans came to national power with the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in 1860. From 1861 to 1896, Sherman held a variety of major political positions, including U.S. senator from Ohio and secretary of the treasury under President Rutherford B. Hayes. After his term as treasury secretary ended, he returned to the Senate and wielded power as one of the top Republican Party leaders. Sherman, who had joined the Radical Republicans during Reconstruction, did not hesitate to move with the Republican Party as its interests shifted from racial equality to promoting business and industry. With his background as chair of the Senate Finance Committee and as secretary of the treasury, Sherman was the most respected Republican of his time in dealing with monetary and financial affairs. Marcus Alonzo Hanna, a wealthy industrialist, considered the Ohio senator “our main dependence in the Senate for the protection of our business interests.” Like Hanna, Sherman believed that government should serve business. His most famous accomplishment, the Sherman Antitrust Act, which authorized the government to break up organizations that restrained competition, embodied this belief. It enacted limited reforms without harming powerful business interests. •

WHILE THE AMERICAN HISTORIES of Andrew Carnegie and John Sherman began very differently, both men played a prominent role in developing the government-business partnership that was crucial to the rapid industrialization of the United States. Carnegie’s organization and management skills helped shape the formation of large-scale business. At the same time, Sherman and his fellow lawmakers provided support for that enterprise, using the power of government to reduce risks for businessmen and to increase incentives for economic expansion. In the view of men like Carnegie and Sherman, government’s primary purpose was, in fact, to advance the agenda and interests of the business community—an agenda they were certain was in the best interests of the country as a whole.

The emphasis Carnegie and Sherman placed on the government-business alliance was, in part, a reaction to the extreme economic volatility of the late nineteenth century. The economy experienced painful depressions in the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s, each accompanied by business failures and mass unemployment. Though recovery came in every instance and industrial output continued to soar, these financial fluctuations left businessmen ever more intent on stabilizing profits, wages, and prices. When faced with harsh economic realities and swift change, businessmen chose organization, cooperation, and government support as strategies to deal with the challenges they confronted.