Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 495

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 404

The New Industrial Economy

The industrial revolution of the late nineteenth century originated in Europe. Great Britain was the world’s first industrial power, but by the 1870s Germany had emerged as a major challenger for industrial dominance, increasing its steel production at a rapid rate and leading the way in the chemical and electrical industries. The dynamic economic growth stimulated by industrial competition quickly crossed the Atlantic. Eager and ambitious American entrepreneurs and engineers soon began applying the latest industrial innovations to U.S. enterprises.

Industrialization transformed the American economy. As industrialization took hold, the U.S. gross domestic product, the output of all goods and services produced annually, quadrupled—from $9 billion in 1860 to $37 billion in 1890. During this same period, the number of Americans employed by industry doubled, as American workers moved from farms to factories and immigrants flooded in from overseas to fill newly created industrial jobs. Moreover, the nature of industry itself changed, as small factories catering to local markets were displaced by large-scale firms producing for national and international markets. The midwestern cities of Chicago, Cincinnati, and St. Louis joined Boston, New York, and Philadelphia as centers of factory production, while the exploitation of the natural resources in the West took on an increasingly industrial character. Trains, telegraphs, and telephones connected the country in ways never before possible. In 1889 the respected economist David A. Wells marveled at what had occurred over the past two decades: “An almost total revolution has taken place, and is yet in progress, in every branch and in every relation of the world’s industrial and commercial system.”

Wells did not exaggerate. From 1870 to 1913, the United States experienced an extraordinary rate of growth in industrial output: In 1870 American industries turned out 23.3 percent of the world’s manufacturing production; by 1913 this figure had jumped to 35.8 percent. In fact, U.S. output in 1913 almost equaled the combined total for Europe’s three leading industrial powers: Germany, the United Kingdom, and France. Of these European countries, only Germany experienced a slight rise in output from 1870 to 1913 (2.5 percent), while Britain’s output dropped a precipitous 17.8 percent and France’s declined 3.9 percent. By the end of the nineteenth century, the United States was surging ahead of northern Europe as the manufacturing center of the world.

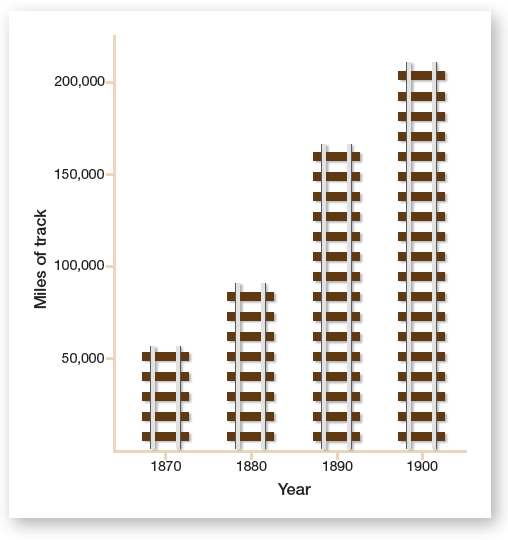

At the heart of the American industrial transformation was the railroad. Large-scale business enterprises would not have developed without a national market for raw materials and finished products. A consolidated system of railroads crisscrossing the nation facilitated the creation of such a market (Figure 16.1). In addition, railroads were direct consumers of industrial products, stimulating the growth of a number of industries through their consumption of steel, wood, coal, glass, rubber, brass, and iron. For example, late-nineteenth-century railroads purchased more than 90 percent of the steel produced in U.S. factories. Finally, railroads contributed to economic growth by increasing the speed and efficiency with which products and materials were transported. One observer guessed that in 1890 if the country had to rely only on roads and waterways instead of trains to ship agricultural and industrial goods, the nation would have lost approximately $560 million, or 5 percent, of its gross national product.

Before railroads could create a national market, they had to overcome several critical problems. In 1877 rail-road lines dotted the country in haphazard fashion. They primarily served local markets and remained unconnected at key points. This lack of coordination stemmed mainly from the fact that each railroad had its own track gauge (the width between the tracks), making shared track use impossible and long-distance travel extremely difficult.

The consolidation of railroads solved many of these problems. In 1886 railroad companies finally agreed to adopt a standard gauge. Railroads also standardized time zones, thus eliminating confusion in train schedules. During the 1870s, towns and cities each set their own time zone, a practice that created discrepancies among them. In 1882 the time in New York City and in Boston varied by 11 minutes and 45 seconds. The following year, railroads agreed to coordinate times and divided the country into four standard time zones. Most cities soon cooperated, but not until 1918 did the federal government legislate the standard time zones that the railroads had first adopted.