Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 547

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 452

The Decline of the Populists

The year 1896 also marked the end of the Populists as a national force, as the party was torn apart by internal divisions over policy priorities and electoral strategy. Populist leaders such as Tom Watson of Georgia did not want the Populist Party to emphasize free silver above the rest of its reform program. Other northern Populists, who either had fought on the Union side during the Civil War or had close relatives who did, such as Mary Lease, could not bring themselves to join the Democrats, the party of the old Confederacy. Nevertheless, the Populist Party officially backed Bryan, but to retain its identity, the party nominated Watson for vice president on its own ticket. After McKinley’s victory, the Populist Party collapsed.

Losing the presidential election alone did not account for the disintegration of the Populists. Several problems plagued the third party. The nation’s recovery from the depression removed one of the Populists’ prime sources of electoral attraction. Despite appealing to industrial workers, the Populists were unable to capture their support. The free silver plank attracted silver miners in Idaho and Colorado, but the majority of workers failed to identify with a party composed mainly of farmers. As consumers of agricultural products, industrial laborers did not see any benefit in raising farm prices. Populists also failed to create a stable, biracial coalition of dispossessed farmers. Most southern white Populists did not truly accept African Americans as equal partners, even though both groups had mutual economic interests. Southern white Populists framed their arguments around class as the central issue driving the exploitation of farmers and workers by wealthy planters and industrialists. However, in the end, they succumbed to racial prejudice.

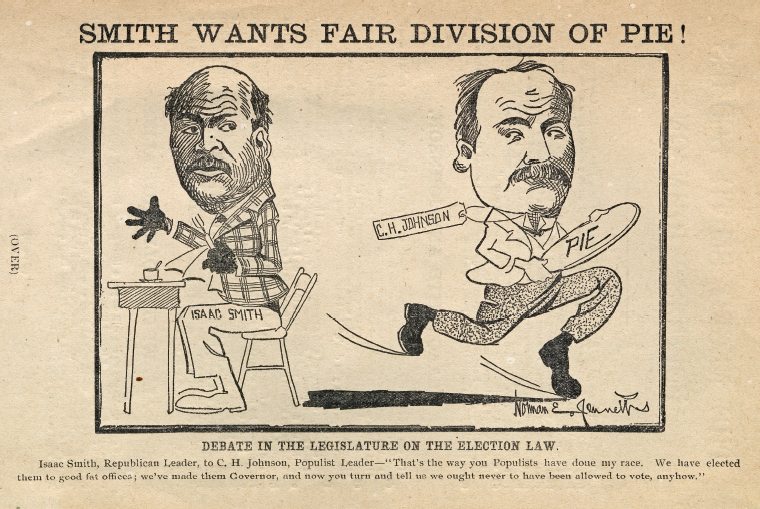

To eliminate Populism’s insurgent political threat, southern opponents found ways to disfranchise black and poor white voters. During the 1890s, southern states inserted into their constitutions voting requirements that virtually eliminated the black electorate and greatly diminished the white electorate. Seeking to circumvent the Fifteenth Amendment’s prohibition against racial discrimination in the right to vote, conservative white lawmakers adopted regulations based on wealth and education because blacks were disproportionately poor and had lower literacy rates. They instituted poll taxes, which imposed a fee for voting, and literacy tests, which asked tricky questions designed to trip up would-be black voters. In 1898 the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of these voter qualifications in Williams v. Mississippi. Recognizing the power of white supremacy, the Populists surrendered to its appeals.

Tom Watson provides a case in point. He started out by encouraging racial unity but then switched to divisive politics. In 1896 the Populist vice presidential candidate, who had assisted embattled black farmers in his home state of Georgia, called on citizens of both races to vote against the crushing power of corporations and railroads. By whipping up racial antagonism against blacks, his Democratic opponents appealed to the racial pride of poor whites to keep them from defecting to the Populists. Chastened by the outcome of the 1896 election and learning from the tactics of his political foes, Watson embarked on a vicious campaign to exclude blacks from voting. “What does civilization owe the Negro?” he bitterly asked. “Nothing! Nothing! NOTHING!!!” Only by disfranchising African Americans and maintaining white supremacy, Watson and other white reformers reasoned, would poor whites have the courage to vote against rich whites.

Nevertheless, even in defeat the Populists left an enduring legacy. Many of their political and economic reforms—direct election of senators, the graduated income tax, government regulation of business and banking, and a version of the subtreasury system (called the Commodity Credit Corporation, created in the 1930s)—became features of reform in the twentieth century. Populists also foreshadowed other attempts at creating farmer-labor parties in the 1920s and 1930s. Perhaps their greatest contribution, however, came in showing farmers that their old individualist ways would not succeed in the modern industrial era. Rather than re-creating an independent political party, most farmers looked to organized interest groups, such as the Farm Bureau, to lobby on behalf of their interests. Whatever their approach, farmers both reflected and contributed to the Age of Organization.

Review & Relate

|

How did the federal government respond to the depression of 1893? |

What were the long-term political consequences of the depression of 1893? |