Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 527

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 431

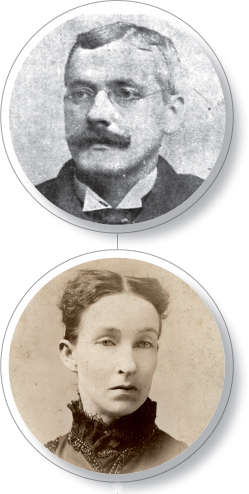

American Histories: John McLuckie and Mary Elizabeth Lease

AMERICAN HISTORIES

John McLuckie worked at the Edgar Thompson Steel Works, Andrew Carnegie’s plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania. A former miner, McLuckie earned $65 a month as an assistant steel roller. In this town of some eleven thousand residents, where nearly everyone worked for Carnegie, the popular McLuckie was twice elected mayor and headed the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, one of the largest unions in the country. Although McLuckie earned a relatively decent income for that time, steelworkers and other industrial laborers had little power over the terms and conditions under which they worked. Visiting fraternal lodges and saloons, where steelworkers congregated after grueling twelve-hour shifts, he spread the message of standing up to corporate leaders. “The constitution of this country,” McLuckie declared, “guarantees all men the right to live, but in order to live we must keep up a continuous struggle.”

In 1892 McLuckie faced the fight of his life when he battled with Carnegie and his plant manager, Henry Clay Frick, over wages and working conditions at the Homestead plant. Like Carnegie, the owners of a host of industries—including railroads, petroleum, textiles, cigarettes, communications, and electric power—had created giant organizations that produced great wealth but also reshaped the working conditions of ordinary Americans. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, workers who labored for these industrial giants sought greater control over their employment by organizing unions to increase their power to negotiate with their employers. The events that unfolded in Homestead in 1892 revealed that workers were vastly outmatched in their struggle with management.

Mary Elizabeth Clyens was the daughter of Irish Catholic parents who came to the United States as part of the great wave of Irish immigration that began in the 1840s. The sixth of eight children, Mary was raised in western Pennsylvania but moved to Kansas in 1870 to teach at a Catholic girls’ school. There she met and married Charles L. Lease, a pharmacist turned farmer. The couple, however, could not support themselves and their four children through farming, and in 1883 the Leases moved to Wichita, where Charles returned to his original profession. In Wichita, Mary found a much wider scope to express her interests and beliefs than she had on the farm. She joined a variety of organizations and worked in support of Irish independence, women’s suffrage, and movements to advance the cause of industrial workers and farmers exploited by big business, railroads, and banks.

Lease entered state and national politics through the Populist Party, which formed in 1890 to challenge the power of large corporations and their political allies, promote the interests of small farmers, and create an alliance between farmers and industrial workers. A mesmerizing speaker, she urged her audiences, according to reporters, to “raise less corn and more hell.” In her book The Problem of Civilization Solved (1895), Lease offered a variety of remedies for late-nineteenth-century America’s economic and political ills, including nationalizing railroad and telegraph lines, increasing the currency supply, and expanding popular democracy. She briefly served as president of the Kansas State Board of Charities when the Populists came to power in 1893, but her tendency to “raise hell” with elected officials in her party led to her removal from office. Following the collapse of the Populist Party in 1896, Lease and her family moved to New York City. She worked as a journalist, divorced her husband, and remained active as a speaker for educational reform and birth control until her death in 1931. •

THE AMERICAN HISTORIES of John McLuckie and Mary Elizabeth Lease were linked by the economic and political forces that shaped the lives of both factory workers and farmers in industrialized America. Even though the culture of rural America was quite different from that of the nation’s industrial towns and cities, farmers and workers faced many of the same problems. Over the course of the late nineteenth century, both groups had seen control over the nature and terms of their work pass from the individual worker or farmer to large corporations and financial institutions. Both groups felt marginalized, dependent, and devalued. McLuckie and Lease were part of a larger effort by laborers and farmers to fight for their own interests against the concentrated economic and political power of big business and to regain control of their lives and their work.