Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 537

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 442

Working-Class Leisure in Industrial America

Despite the economic hardships and political repression that industrial laborers faced in the late nineteenth century, workers carved out recreational spaces over which they had control and that offered relief from their backbreaking toil. Time clocks, often viewed as an annoying part of scientific management, nevertheless clearly emphasized the difference between working and nonworking hours. For many, Sunday became a day of rest that took on a secular flavor.

Working-class leisure patterns varied by gender, race, and region. Women did not generally attend spectator sporting events, such as baseball and boxing matches, which catered to men. Nor did they find themselves comfortable in union halls and saloons, where men found solace in drink. Working-class wives preferred to gather to prepare for births, weddings, and funerals or to assist neighbors who lost their homes because of fire, death, or greedy landlords.

Once employed, working-class daughters found a greater measure of independence and free time by living in rooming houses on their own. Women’s wages were only a small fraction of men’s earnings, so working women rarely made enough money to support a regular social life along with paying for rent, food, and clothes. Still, they found ways to enjoy their free time. Some single women went out in groups, hoping to meet men who would pay for drinks, food, or a vaudeville show. Others dated so that they knew they would be taken care of for the evening. Some of the men who “treated” on a date assumed a right to sexual favors in return, and some of these women then expected men to provide them with housing and gifts in exchange for an ongoing sexual relationship. Thus emotional and economic relationships became intertwined in complicated ways.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, dance halls flourished as one of the mainstays of working-class communities throughout the nation. Huge dance palaces that held three thousand to five thousand people were built in the entertainment districts of most large cities. They made their money by offering music with lengthy intermissions for the sale of drinks and refreshments. Women and men also attended cabarets, some of which were racially integrated. In so-called red-light districts of the city, prostitutes earned money entertaining their clients with a variety of sexual pleasures.

Not all forms of leisure were strictly segregated along class lines. A number of forms of cheap entertainment appealed not only to working-class women and men but also to their middle-class counterparts. By the turn of the twentieth century, most large American cities featured amusement parks. Brooklyn’s Coney Island stood out as the most spectacular of these sprawling playgrounds of fun and excitement. In 1884 the world’s first roller coaster was built at Coney Island, providing thrills to those brave enough to ride it. Chicago residents could enjoy the Ferris wheel, which appeared at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Designed by George Ferris, who operated a firm specializing in structural steel, the wheel rose 250 feet in the air, was propelled by two 1,000-horsepower steam engines, and accommodated 1,440 riders at a time.

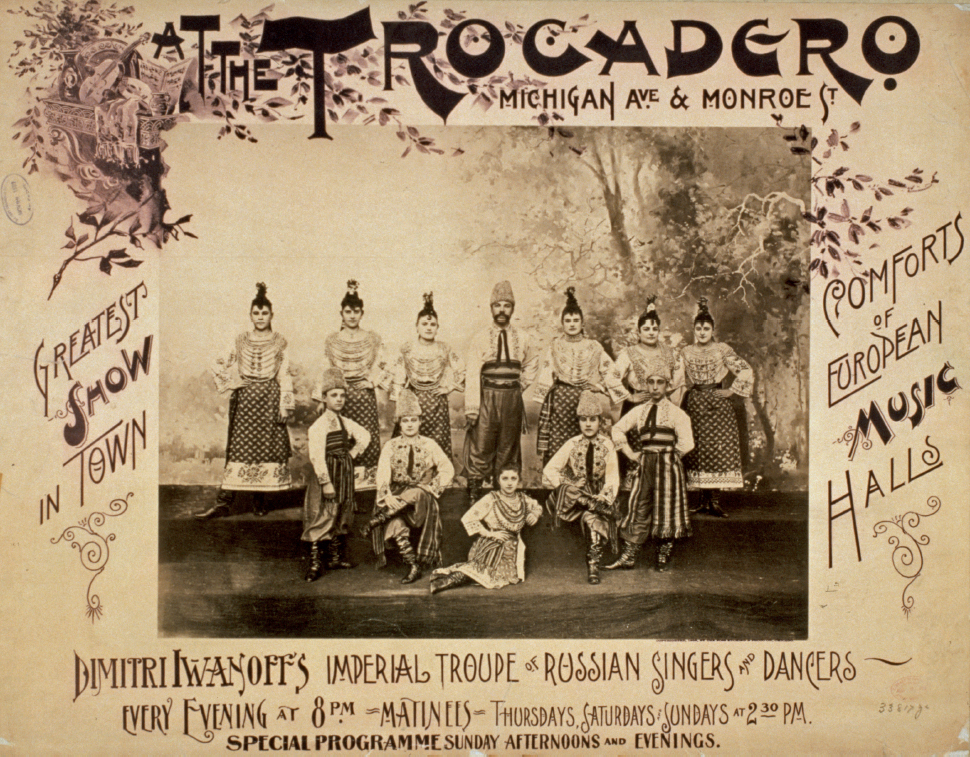

Vaudeville houses—with their minstrel shows (whites in blackface) and comedians, singers, and dancers—brought howls of laughter to working-class audiences. Nickelodeons charged five cents to watch short films. Live theater generally attracted more wealthy patrons; however, the Yiddish theater, which flourished on New York’s Lower East Side, and other immigrant-oriented stage productions appealed mainly to working-class audiences.

Southern workers also enjoyed music in their leisure time. Cheap banjoes and fiddles were mass-produced by the end of the nineteenth century. Pianos also became readily available, and one mountain boy, on hearing a piano for the first time, commented that it was the “beautifullest thing he had ever heard.”

Itinerant musicians entertained audiences throughout the South. Lumber camps, which employed mainly African American men, offered a popular destination for these musicians. Each camp contained a “barrelhouse,” also called a “honky tonk” or a “juke joint.” Besides showcasing music, the barrelhouse also gave workers the opportunity to “shoot craps, dice, drink whiskey, dance, every modern devilment you can do,” as one musician who played there recalled. From the Mississippi delta emerged a new form of music—the blues. W. C. Handy, “the father of the blues,” discovered this music in his travels through the delta, where he observed that southern blacks “sang about everything. Trains, steamboats, steam whistles, sledge hammers, fast women, mean bosses, stubborn mules.” They performed these songs of woe accompanying themselves with anything that would make a “musical sound or rhythmical effect, anything from a harmonica to a washboard.” Meanwhile in New Orleans, an amalgam of black musical forms evolved into jazz. Musicians such as “Jelly Roll” Morton experimented with a variety of sounds, putting together African and Caribbean rhythms with European music, mixing pianos with clarinets, trumpets, and drums. Blues and jazz spread throughout the South, appearing in juke joints in Atlanta and Memphis, where men and women danced the night away.

In mountain valley mill towns, southern white residents preferred “old time” music, but with a twist. Originally enjoyed by British settlers, traditional ballads and folk songs concerned the deeds of kings and princes; rural southerners modified the lyrics to extol the exploits of outlaws and adventurers. Country music, which combined romantic ballads and folk tunes to the accompaniment of guitars, banjoes, and organs, emerged as a distinct brand of music by the twentieth century. As with African Americans, in the late nineteenth century working-class and rural whites found new and exciting types of music to entertain them in their leisure. Religious music also appealed to both white and black audiences and drew crowds to evangelical revivals held in tents on acres of grass fields.

Mill workers also amused themselves by engaging in social, recreational, and religious activities. Women visited each other and exchanged confidences, gossip, advice on child rearing, and folk remedies. Men from various factories organized baseball teams that competed in leagues with one another. Managers of a mill in Charlotte, North Carolina, admitted that they “frequently hired men better known for their batting averages than their work records.”

Review & Relate

|

How did industrialization change the American workplace? What challenges did it create for American workers? |

How did workers resist the concentrated power of industrial capitalists in the late nineteenth century, and why did such efforts have only limited success? |