Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 563

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 460

Immigrants Arrive from Many Lands

Immigration to the United States was part of a worldwide phenomenon. In addition to the United States, European immigrants also journeyed to other countries in the Western Hemisphere, especially Canada, Argentina, Brazil, and Cuba. Others left China, Japan, and India and migrated to Southeast Asia and Hawaii. From England and Ireland, migrants ventured to other parts of the British empire, in-cluding Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. As with those who came to the United States, these immigrants left their homelands to find new job opportunities or to obtain land to start their own farms. In countries like Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, white settlers often pushed aside native peoples—Aborigines in Australia, Maori in New Zealand, and blacks in South Africa—to make communities for themselves. Whereas most immigrants chose to relocate voluntarily, some made the move bound by labor contracts that limited their movement during the terms of the agree-ment. Chinese, Mexican, and Italian workers made up a large portion of this group.

The late nineteenth century saw a shift in the country of origin of immigrants to the United States: Instead of coming from northern and western Europe, many now came from southern and eastern European countries, most notably Italy, Greece, Austria-Hungary, Poland, and Russia. In 1882 around 789,000 immigrants entered the United States, 87 percent of whom came from northern and western Europe. By contrast, twenty-five years later in 1907, of the 1,285,000 newcomers who journeyed to America, 81 percent originated from southern and eastern Europe.

Most of those settling on American shores after 1880 were Catholic or Jewish and hardly knew a word of English. They tended to be even poorer than immigrants who had arrived before them, coming mainly from rural areas and lacking suitable skills for a rapidly expanding industrial society. In the words of one historian, who could easily have been describing Beryl Lassin’s life: “Jewish poverty [in Russia] is a kind of marvel for . . . it has origins in fathers and grandfathers who have been wretchedly poor since time immemorial.” Even after relocating to a new land and a new society, such immigrants struggled to break patterns of poverty that were, in many cases, centuries in the making.

Immigrants came from other parts of the world as well. From 1860 to 1924, some 450,000 Mexicans migrated to the U.S. Southwest. Many traveled to El Paso, Texas, near the Mexican border, and from there hopped aboard one of three railroad lines to jobs on farms and in mines, mills, and construction. Cubans, Spaniards, and Bahamians traveled to the Florida cities of Key West and Tampa, where they established and worked in cigar factories. Tampa grew from a tiny village of a few hundred people in 1880 to a city of 16,000 in 1900. Although Congress had excluded Chinese immigration after 1882, it did not close the door to migrants from Japan. Unlike the Chinese, the Japanese had not competed with white workers for jobs on railroad and other construction projects. Moreover, Japan had emerged as a major world power in the late nineteenth century and gained some grudging respect from American leaders by defeating Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Some 260,000 Japanese arrived in the United States during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Many of them first settled in Hawaii and then moved to the West Coast states of California, Oregon, and Washington, where they worked as farm laborers and gardeners and established businesses catering to a Japanese clientele. Nevertheless, like the Chinese before them, Japanese immigrants were considered part of an inferior “yellow race” and encountered discrimination in their West Coast settlements.

This wave of immigration changed the composition of the American population. By 1910 one-third of the population was foreign-born or had at least one parent who came from abroad. Foreigners and their children made up more than three-quarters of the population of New York City, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Minneapolis, and San Francisco. Immigration, though not as extensive in the South as in the North, also altered the character of southern cities. About one-third of the population of Tampa, Miami, and New Orleans consisted of foreigners and their descendants. The borderland states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and southern California contained similar percentages of immigrants, most of whom came from Mexico.

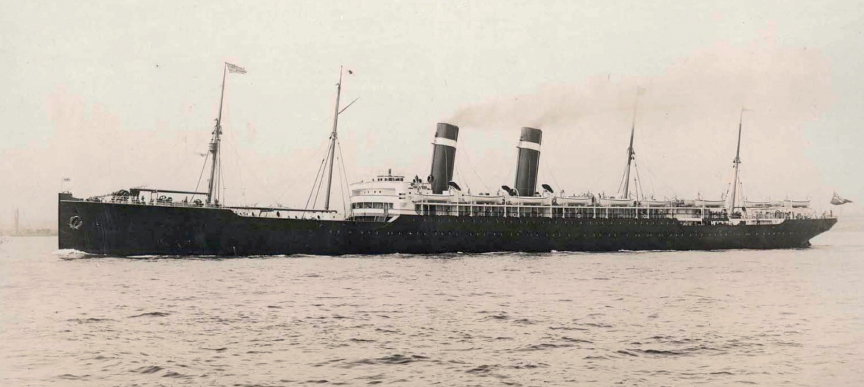

These immigrants came to the United States largely for economic, political, and religious reasons. Nearly all were poor and expected to find ways to make money in America. U.S. railroads and steamship companies advertised in Europe and recruited passengers by emphasizing economic opportunities in the United States. Early immigrants wrote to relatives back home extolling the virtues of what they had found, perhaps exaggerating their success. However, for people barely making a living, or for those subject to religious discrimination and political repression, what did it matter if they arrived in America and the streets were not paved in gold, as legend had it? In fact, if many of the streets were not paved at all, at least the immigrants could get jobs paving them!

The importance of economic incentives in luring immigrants is underscored by the fact that millions returned to their home countries after they had earned sufficient money to establish a more comfortable lifestyle. Of the more than 27 million immigrants from 1875 to 1919, 11 million returned home (Table 18.1). One immigrant from Canton, China, accumulated a small fortune as a merchant on Mott Street, in New York City’s Chinatown. According to residents of his hometown in China, “[Having] made his wealth among the barbarians this man had faithfully returned to pour it out among his tribesmen, and he is living in our village now very happy.” Jews, Mexicans, Czechs, and Japanese had the lowest rates of return. Immigrant groups facing religious or political persecution in their homeland were the least likely to return. It is highly doubtful that a poor Jewish immigrant like Beryl Lassin would have received a warm welcome home in his native Russia, if he had been allowed to return at all.

| Year | Arrivals | Departures | Percentage of Departures to Arrivals |

| 1875–1879 | 956,000 | 431,000 | 45% |

| 1880–1884 | 3,210,000 | 327,000 | 10% |

| 1885–1889 | 2,341,000 | 638,000 | 27% |

| 1890–1894 | 2,590,000 | 838,000 | 32% |

| 1895–1899 | 1,493,000 | 766,000 | 51% |

| 1900–1904 | 3,575,000 | 1,454,000 | 41% |

| 1905–1909 | 5,533,000 | 2,653,000 | 48% |

| 1910–1914 | 6,075,000 | 2,759,000 | 45% |