Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 565

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 462

Creating Immigrant Communities

Immigrants were processed at their port of entry, and the government played no role in their relocation in America. New arrivals were left to search out transplanted relatives and other countrymen on their own. In cities such as New York, Boston, and Chicago, immigrants occupied neighborhoods that took on the distinct ethnic characteristics of the groups that inhabited them. A cacophony of different languages echoed in the streets as new residents continued to communicate in their mother tongues. The neighborhoods of immigrant groups often were clustered together, so residents were as likely to learn phrases in their neighbors’ languages as they were to learn English.

The formation of ghettos—neighborhoods dominated by a single ethnic, racial, or class group—eased immigrants’ transition into American society. Without government assistance or outside help, these communities assumed the burden of meeting some of the challenges that immigrants faced in adjusting to their new environment. Living within these ethnic enclaves made it easier for immigrants to find housing, hear about jobs, buy food, and seek help from those with whom they felt most comfortable. Mutual aid societies sprang up to provide social welfare benefits, including insurance payments and funeral rites. “A landsman died in the factory,” a founder of one such Jewish association explained, and the worker was buried in an unmarked grave. When his Jewish neighbors heard about it, “his body [was] dug up, and the decision taken to start our organization with a cemetery.” Group members established social centers where immigrants could play cards or dominoes, chat and gossip over tea or coffee, host dances and benefits, or just relax among people who shared a common heritage. In San Francisco’s Chinatown, the largest Chinese community in California, such organizations usually consisted of people who had come from the same towns in China. These groups performed a variety of services, including finding jobs for their members, resolving disputes, campaigning against anti-Chinese discrimination, and sponsoring parades and other cultural activities. One society member explained: “We are strangers in a strange country. We must have an organization to control our country fellows and develop our friendship.”

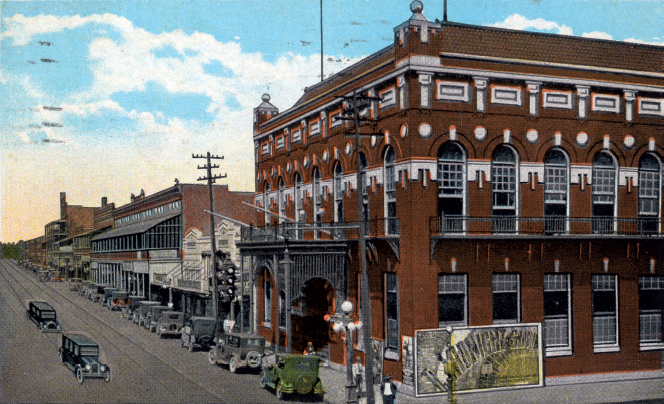

The same impulse to band together occurred in immigrant communities throughout the nation. On the West Coast, Japanese farmers joined kenjinkai, which not only provided social activities but also helped first-generation immigrants locate jobs and find housing. In Ybor City, Tampa’s cigar-making section, mutual aid organizations rose to meet the needs of Spaniards, Cubans, Afro-Cubans, and Italians. El Centro Español sponsored dances catering to Spaniards, only to be outdone by the rival El Centro Asturiano, which constructed a building that contained a 1,200-seat theater with a 27-by-80-foot stage, “$4,000 worth of modern lighting fixtures, a cantina, and a well stocked biblioteca (library).” Cubans constructed their own palatial $60,000 clubhouse, El Circulo Cubano, with lovely stained-glass windows, a pharmacy, a theater, and a ballroom. Less splendid and more economical, La Union Martí-Maceo became the home away from home for Tampa’s Afro-Cubans. Besides the usual attractions, the club sponsored a baseball team that competed against other Latin teams. The establishment of such clubs and cultural centers speaks to the commitment of Tampa’s immigrant groups to enhance their communities—a commitment backed up with significant financial expenditures. (See e-Document Project 18: Class and Leisure in the American City.)

Besides family and civic associations, churches and synagogues provided religious and social activities for ghetto dwellers. The number of Catholic churches nationwide more than tripled—from 3,000 in 1865 to 10,000 in 1900. Churches celebrated important landmarks in their parishion-ers’ lives—births, baptisms, weddings, and deaths—in a far warmer and more personal manner than did clerks in city hall. Like mutual aid societies, churches offered food and clothing to those who were ill or unable to work and fielded sports teams to compete in recreational leagues. Immigrants altered the religious practices and rituals in their churches to meet their own needs and expectations, many times over the objections of their clergy. Various ethnic groups challenged the orthodox practices of the Catholic Church and insisted that their parishes adopt religious icons that they had worshipped in the old country. These included patron saints or protectresses from Old World towns, such as the Madonna del Carmine, whom Italian Catholics in New York’s East Harlem celebrated with an annual festival that their priests considered a pagan ritual. Women played the predominant role in running these street festivities. German Catholics challenged Vatican policy by insisting that each ethnic group have its own priests and parishes. Some Catholics, like Mary Vik, who lived in rural areas that did not have a Catholic church in the vicinity, attended services with local Christians from other denominations.

Religious worship also varied among Jews. German Jews had arrived in the United States in an earlier wave of immigration than their eastern European coreligionists. By the early twentieth century, they had achieved some measure of economic success and founded Reform Judaism, with Cincinnati, Ohio, as its center. This brand of Judaism relaxed strict standards of worship, including absolute fidelity to kosher dietary laws, and allowed prayers to be said in English. By contrast, eastern European Jews, like Beryl Lassin, observed the traditional faith and went to shul (synagogue) on a regular basis, maintained a kosher diet, and prayed in Hebrew.

With few immigrants literate in English, foreign-language newspapers proliferated to inform their readers of local, national, and international events. Between the mid-1880s and 1920, 3,500 new foreign-language newspapers came into existence. These newspapers helped sustain ethnic solidarity in the New World as well as maintain ties to the Old World. Newcomers could learn about social and cultural activities in their communities and keep abreast of news from their homeland. German-language tabloids dominated the field and featured such dailies as the New Yorker Staatszeitung, the St. Louis Anzeiger des Westens, the Cincinnati Volkesblatt, and the Wisconsin Banner.

Like other communities with poor, unskilled populations, immigrant neighborhoods bred crime. Young men joined gangs based on ethnic heritage and battled with those of other immigrant groups to protect their turf. Adults formed underworld organizations—some of them tied to international criminal syndicates, such as the Mafia—that trafficked in prostitution, gambling, robbery, and murder. Tongs (secret organizations) in New York City’s and San Francisco’s Chinatowns, which started out as mutual aid societies, peddled vice and controlled the opium trade, gambling, and prostitution in their communities. A survey of New York City police and municipal court records from 1898 concluded that Jews “are prominent in their commission of forgery, violation of corporation ordinance, as disorderly persons (failure to support wife or family), both grades of larceny, and of the lighter grade of assault.”

Crime was not the only social problem that plagued immigrant communities. Newspapers and court records reported husbands abandoning their wife and children, engaging in drunken and disorderly conduct, or abusing their family. Boarders whom immigrant families took into their homes for economic reasons also posed problems. Cramped spaces created a lack of privacy, and male boarders sometimes attempted to assault the woman of the house while her husband and children were out to work or in school. Finally, generational conflicts within families began to develop as American-born children of immigrants questioned their parents’ values. Daughters born in America sought to loosen the tight restraints imposed by their parents. If they worked outside the home, young women were expected to turn their wages over to their parents. A young Italian woman, however, displayed her independence after receiving her first paycheck. “I just went downtown first and I spent a lot, more than half of my money,” she admitted. “I just went hog wild.” Thus the social organizations and mutual aid societies that immigrant groups established were more than a simple expression of ethnic solidarity and pride. They were also a response to the very real problems that challenged the health and stability of immigrant communities.

Explore

See Document 18.1 for a depiction of one immigrant family’s intergenerational conflict.