Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 591

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 483

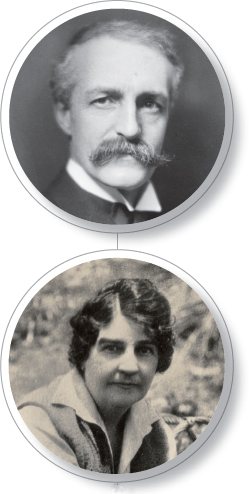

American Histories: Gifford Pinchot and Geneva Stratton-Porter

AMERICAN HISTORIES

Gifford Pinchot grew up on a lavish Connecticut estate catered to by tutors and governesses and vacationing in rural areas, where Gifford learned to hunt, fish, and enjoy the splendor of nature. Yet Pinchot rejected a life of leisure and gentility. Like other affluent young men and women of his time, Pinchot sought to make his mark through public service, in his case by working to conserve and protect America’s natural resources. In 1885, following his father’s advice, Gifford entered Yale University to study forestry. However, the university did not offer a forestry program, reflecting the predominant view that the nation’s natural resources were, for all practical purposes, unlimited. Pinchot cobbled together courses in various scientific fields at Yale, but he knew that after graduating his only option for further study was to travel to Europe, where forests were treated as crops that needed care and replenishing.

By the time Pinchot returned in 1890, many Americans had begun to see the need to conserve the nation’s forests, waterways, and oil and mineral deposits and to protect its wild spaces. Drawing on his training as a scientist and his experiences in Europe, Pinchot advocated the use of natural resources by sportsmen and businesses under carefully regulated governmental authority. Appointed to head the Federal Division of Forestry in 1898, Pinchot found a vigorous ally in the White House when Theodore Roosevelt took office in 1901 after William McKinley’s assassination. In 1907 Pinchot began to speak of the need for conservation, which he defined as “the use of the natural resources now existing on this continent for the benefit of the people who live here now.” This use of resources included responsible business practices in industries such as logging and mining.

Not all environmentalists agreed. In contrast to Pinchot, author and nature photographer Geneva (Gene) Stratton-Porter focused her energies on preservation, the protection of public land from any private development and the creation of national parks. Born in 1863 in Wabash County, Indiana, Stratton-Porter spent her childhood on a farm roaming through fields, watching birds, and observing “nature’s rhythms.” After marrying in 1886, Stratton-Porter took up photography and hiked into the wilderness of Indiana to take pictures of wild birds.

Stratton-Porter built a reputation as a nature photographer. She also published a series of novels and children’s books that revealed her vision of the harmony between human beings and nature. She urged readers to preserve the environment for plant life and wildlife so that men and women could lead a truly fulfilling existence on Earth and not destroy God’s creation. Of all the preservationists, Stratton-Porter reached the widest audience. Five of her books sold more than a million copies, and several were made into movies. •

THE AMERICAN HISTORIES of Gifford Pinchot and Gene Stratton-Porter reveal the efforts of just two of the many individuals who searched for ways to control the damaging impact of modernization on the United States. From roughly 1900 to 1917, many Americans sought to bring some order out of the chaos accompanying rapid industrialization and urbanization. Despite the magnitude of the issues they targeted, those who believed in the need to combat the problems of industrial America possessed an optimistic faith—sometimes derived from religious principles, sometimes from a secular outlook—that they could relieve the stresses and strains that modern life brought. Such people were not bound together by a single, rigid ideology. Instead, they were united by faith in the notion that if people joined together and applied human intelligence to the task of improving the nation, progress was inevitable. So widespread was this hopeful conviction that we call this period the Progressive Era.

In pursuit of progress and stability, reformers tried to control the behavior of groups they considered a threat to the social order. Equating difference with disorder, many progressives tried to impose white middle-class standards of behavior on immigrant populations. Some sought to eliminate the “problem” altogether by curtailing further immigration from southern and eastern Europe. Many white progressives, particularly in the South, supported segregation and disfranchisement, which limited opportunities for African Americans. At the same time, however, black progressives and their white allies created organizations dedicated to securing racial equality.