Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 593

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 486

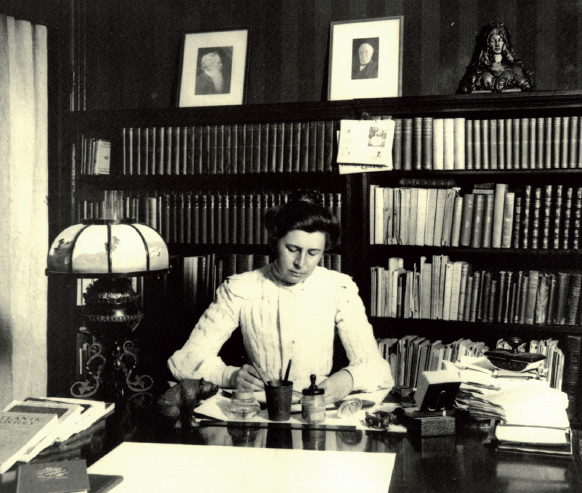

Muckrakers

The growing desire for reform at the turn of the century received a boost from investigative journalists known as muckrakers. Popular magazines such as McClure’s and Collier’s sought to increase their readership by publishing exposés of corruption in government and the shady operations of big business. Filled with details uncovered through intensive research, these articles had a sensationalist appeal that both informed and aroused their mainly middle-class readers. In 1902 journalist Ida Tarbell lambasted the ruthless and dishonest business practices of the Rockefeller family’s Standard Oil Company, the model of corporate greed. Lincoln Steffens wrote about machine bosses’ shameful rule in cities such as Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Minneapolis, New York, St. Louis, and Philadelphia. Ida B. Wells, a Memphis journalist, wrote scathing articles and pamphlets condemning the lynching of African Americans. Other muckrakers exposed fraudulent practices in insurance companies, child labor, drug abuse, and prostitution.

Ironically, President Theodore Roosevelt coined the term muckraker in 1906 not as a compliment but as a sign of disgust for journalists he thought were more interested in making sensationalist charges than in carefully documenting their stories. He compared them to the character in John Bunyan’s novel Pilgrim’s Progress who was so absorbed in looking at the filth (muck) on the ground that he did not see a beautiful gift offered to him. Roosevelt feared that if muckraking became too sensational and unrestrained, it would threaten moderate reform and encourage more radical alternatives. Yet muckrakers did succeed in raising middle-class awareness and generated wide support for the political reforms that Roosevelt and other progressives proposed.

Review & Relate

|

What late-nineteenth-century trends and developments influenced the progressives? |

Why did the progressives focus on urban and industrial America? |