Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 594

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 487

Female Progressives and the Poor

Women played the leading role in efforts to improve the lives of the impoverished. Jane Addams, the daughter of a wealthy businessman, had toured Europe after graduating from a women’s college in Illinois. The Toynbee Hall settlement house in London impressed her for its work in helping poor residents of the area. In 1889 Addams, after returning home to Chicago, and her friend Ellen Starr established Hull House as a center for social reform in the northwest neighborhood of the city. Hull House inspired a generation of young women to work directly in immigrant communities. Many were college-educated, professionally trained women who were shut out of jobs in male-dominated professions. Staffed mainly by women, settlement houses became all-purpose urban support centers. Not only did they provide recreational facilities, social activities, and educational classes for neighborhood residents, but they also became launching pads for campaigns aimed at improving living and working conditions for the urban poor. Calling on women to take up civic housekeeping, Addams maintained that women could protect their individual households from the chaos of industrialization and urbanization only by attacking the sources of that chaos in the community at large.

Explore

See Document 19.1 for a description of one civic housekeeping effort.

Settlement house and social workers occupied the front lines of humanitarian reform, but they found considerable support from women’s clubs. Formed after the Civil War, these local groups provided protected spaces for middle-class women to meet, share ideas, and work on common projects. In 1890 these local associations were brought together under the umbrella of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, which by the end of the nineteenth century counted 495 chapters and 160,000 members. By 1900 these clubs—which had initially been devoted to discussions of religion, culture, and science—began to help the needy and lobby for social justice legislation. “Since men are more or less closely absorbed in business,” one club woman remarked about this civic awakening, “it has come to pass that the initiative in civic matters has devolved largely upon women.” Starting out in towns and cities, club women carried their message to state and federal governments and campaigned for legislation that would establish social welfare programs for working women and their children.

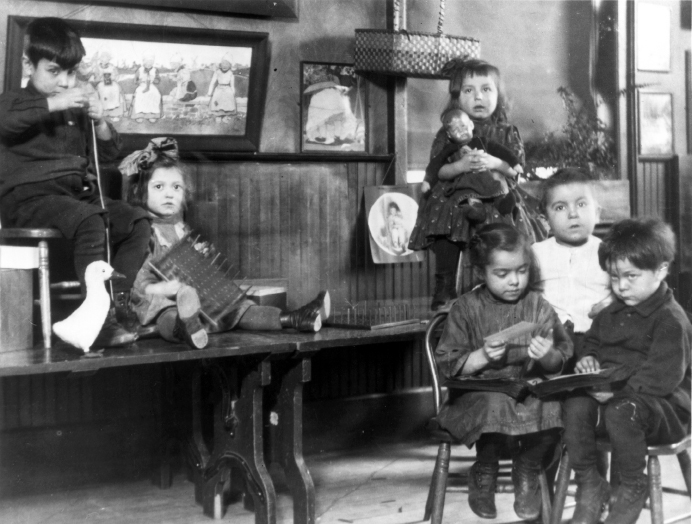

In an age of strict racial segregation, African American women formed their own clubs to undertake reform activities. They sponsored day care centers, kindergartens, and work and home training projects. The activities of black club women, like those of white club women, reflected a class bias, and they tried to lift up poorer blacks to ideals of middle-class womanhood. In doing so, they challenged white supremacist notions that black women and men were incapable of raising healthy and strong families. By 1916 the National Association of Colored Women, whose motto was “lifting as we climb,” boasted 1,000 clubs and 50,000 members.

White working-class women also organized, but because of employment discrimination there were few, if any, black female industrial workers to join them. Building on the settlement house movement and together with middle-class and wealthy women, working-class women founded the National Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) in 1903. The WTUL was dedicated to securing higher wages and improved working conditions, and its slogan, “The Eight-Hour Day: A Living Wage; to Guard the Home,” expressed its objectives. The WTUL recognized that many women needed to earn an income to help support their families, and it backed protective legislation based on women’s specific needs.

Believing women to be physically weaker than men, most female reformers advocated special legislation to protect women in the workplace. They campaigned for state laws prescribing the maximum number of hours women could work, and they succeeded in 1908 when they won a landmark victory in the Supreme Court in Muller v. Oregon, which upheld an Oregon law establishing a ten-hour workday for women. These reformers also convinced lawmakers in forty states to establish pensions for mothers and widows. In 1912 their focus shifted to the federal government with the founding of the Children’s Bureau in the Department of Commerce and Labor. Headed by Julia Lathrop, an Addams disciple from Illinois, the bureau attracted female reformers, collected sociological data, and devised a variety of publicly funded social welfare measures. In 1916 Congress enacted a law banning child labor under the age of fourteen (it was declared unconstitutional in 1918). In 1921 Congress passed the Shepherd-Towner Act, which allowed nurses to offer maternal and infant health care information to mothers.

Not all women believed in the idea of protective legislation for women. In 1898 Charlotte Perkins Gilman published Women and Economics, in which she argued against the notion that women were ideally suited for domesticity. She contended that women’s accepted relationship to men was unnatural. “We are the only animal species in which the female depends on the male for food,” Gilman wrote, “the only animal species in which the sex relation is also the economic relation.” Emphasizing the need for economic independence, Gilman advocated the establishment of communal kitchens that would free women from household chores and allow them to compete on equal terms with men in the workplace. Emma Goldman, an anarchist critic of capitalism and middle-class sexual morality, also spoke out against the kind of marriage that made women “keep their mouths shut and their wombs open.” She endorsed “free love,” in which women and men enjoyed sex equally. These and a growing number of other women did not consider themselves reformers so much as radicals, and even feminists—women who aspire to reach their full potential and gain access to the same opportunities as men.