Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 596

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 488

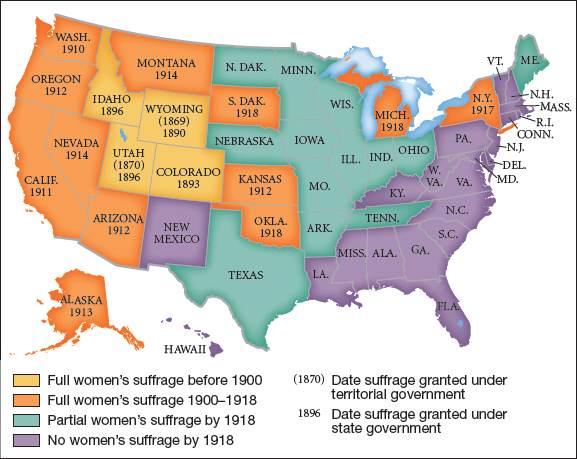

Fighting for Women’s Suffrage

Until 1910, women did not have the right to vote, except in a handful of western states (see chapter 15). The passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments had disappointed many campaigners for women’s suffrage. Although the amendments extended citizenship to African Americans and protected the voting rights of black men, they left women, both white and black, ineligible to vote. The Fourteenth Amendment had underscored this distinction by specifically referring to “male inhabitants” in its provision dealing with voting for national officials. Following Reconstruction, the two major organizations campaigning for women’s suffrage at the state and national levels—Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s National Woman Suffrage Association and Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe’s American Woman Suffrage Association—failed to achieve major victories. In 1890 the two groups combined to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and by 1918 women could vote in fifteen states and the territory of Alaska (Map 19.1).

Suffragists included a broad coalition of supporters and based their campaign on a variety of arguments. Reformers such as Jane Addams stressed that suffrage for women would be an extension of “civic housekeeping.” They attributed corruption in politics to the absence of women’s maternal influence. In this way, mainstream suffragists couched their arguments within traditional conceptions of women as family nurturers. They claimed that men should not fear women’s desire to vote; rather, they should see it as an expansion of traditional household duties into the public sphere. By contrast, suffragists such as Alice Paul rejected arguments stressing women’s domesticity and their inherent difference from men. Paul, who had earned a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania and two law degrees, asserted that women deserved the vote on the basis of their equality with men as citizens. She founded the National Woman’s Party and in 1923 proposed that Congress adopt an Equal Rights Amendment to provide full legal equality to women.

Traditionalists, both male and female, fought against women’s suffrage. They believed that women were best suited by nature to devote themselves to their families and leave the rough-and-tumble world of politics to men. Suffrage opponents insisted that extending the right to vote to women would destroy the home, lead to the moral degeneracy of children, and tear down the social fabric of the country.

Campaigns for women’s suffrage did not apply to all women. White suffragists in the South often manipulated racial prejudice to support female enfranchisement. In the wake of the Populist Party’s efforts to recruit black voters in the 1890s, most of the former Confederate states rewrote their constitutions or enacted statutes removing African Americans from the voter rolls through the use of poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clause requirements. Although they did not constitute a majority, outspoken white suffragists such as Rebecca Latimer Felton from Georgia, Belle Kearney from Mississippi, and Kate Gordon from Louisiana used white supremacist arguments to make a case for white women gaining the vote. As long as even a fraction of black men voted and the Fifteenth Amendment continued to exist, they contended that allowing southern white women to vote would preserve white supremacy by offsetting black men’s votes. These arguments also had a class component. Poll taxes and literacy tests disfranchised poor, uneducated whites. Extending the vote to white women would benefit mainly those in the middle class who had some education and enough family income to satisfy restrictive literacy test and poll tax requirements.

Many middle-class women outside the South used similar reasoning, but they targeted newly arrived immigrants instead of African Americans. Many Protestant women and men viewed Catholics and Jews from southern and eastern Europe as racially inferior and spiritually dangerous. They blamed such immigrants for the ills of the cities in which they congregated, and some suffragists believed that the vote of middle-class Protestant women would help clean up the mess the immigrants created. One supporter proclaimed that suffragists “had always recognized the usefulness of woman suffrage as a counterbalance to the foreign vote.”

African American women challenged these racist arguments and mounted their own drive for female suffrage. If “white women needed the vote to acquire advantages and protection of their rights,” Adella Hunt Logan of Tuskegee, Alabama, remarked, “then Black women needed the vote even more so.” African American women had an additional incentive to press for enfranchisement. As the target of white sexual predators during slavery and its aftermath, some black women saw the vote as a way to address this problem. Although they did not gain much support from the National American Woman Suffrage Association, by 1916 African American women worked through the National Association of Colored Women and formed suffrage clubs throughout the nation.

Explore

See Document 19.2 for an argument for suffrage for black women.

The campaign for women’s suffrage in the United States was part of an international movement. Victories in New Zealand (1893), Australia (1902), and Norway (1913) spurred on American suffragists. In the 1910s, radical American activists found inspiration in the militant tactics employed by some in the British suffrage movement. Activists such as Alice Paul conducted wide-ranging demonstrations in Washington, D.C., including chaining themselves to the gates of the White House. Although mainstream suffrage leaders denounced these new tactics, they gained much-needed publicity for the movement, which in turn aided the lobbying efforts of more moderate activists. In 1919 Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment granting women the vote. The following year, the amendment was ratified by the states.