Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 14

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 14

Europeans Explore the Americas

Columbus made two more voyages to the Caribbean to claim land for Spain and sought to convince those who accompanied him to build houses, plant crops, and cut logs for forts. But the men had come for gold, and when the Indians stopped trading willingly, the Spaniards used force to claim their riches. Columbus sought to impose a more rigid discipline but failed. On his final voyage, he was forced to introduce a system of encomiendas, by which leading men received land and the labor of all Indians residing on it. Although he boasted to the Spanish crown that he had “placed under their Highnesses’ sovereignty more land than there is in Africa and Europe,” Columbus had lost the support of the Spanish authorities by the time he died in 1506. The islands he discovered were quickly dissolving into chaos as traders and adventurers fought with Indians and one another over the spoils of conquest. By then, no one believed that he had discovered a route to China, and few people understood the revolutionary importance of the lands he had found.

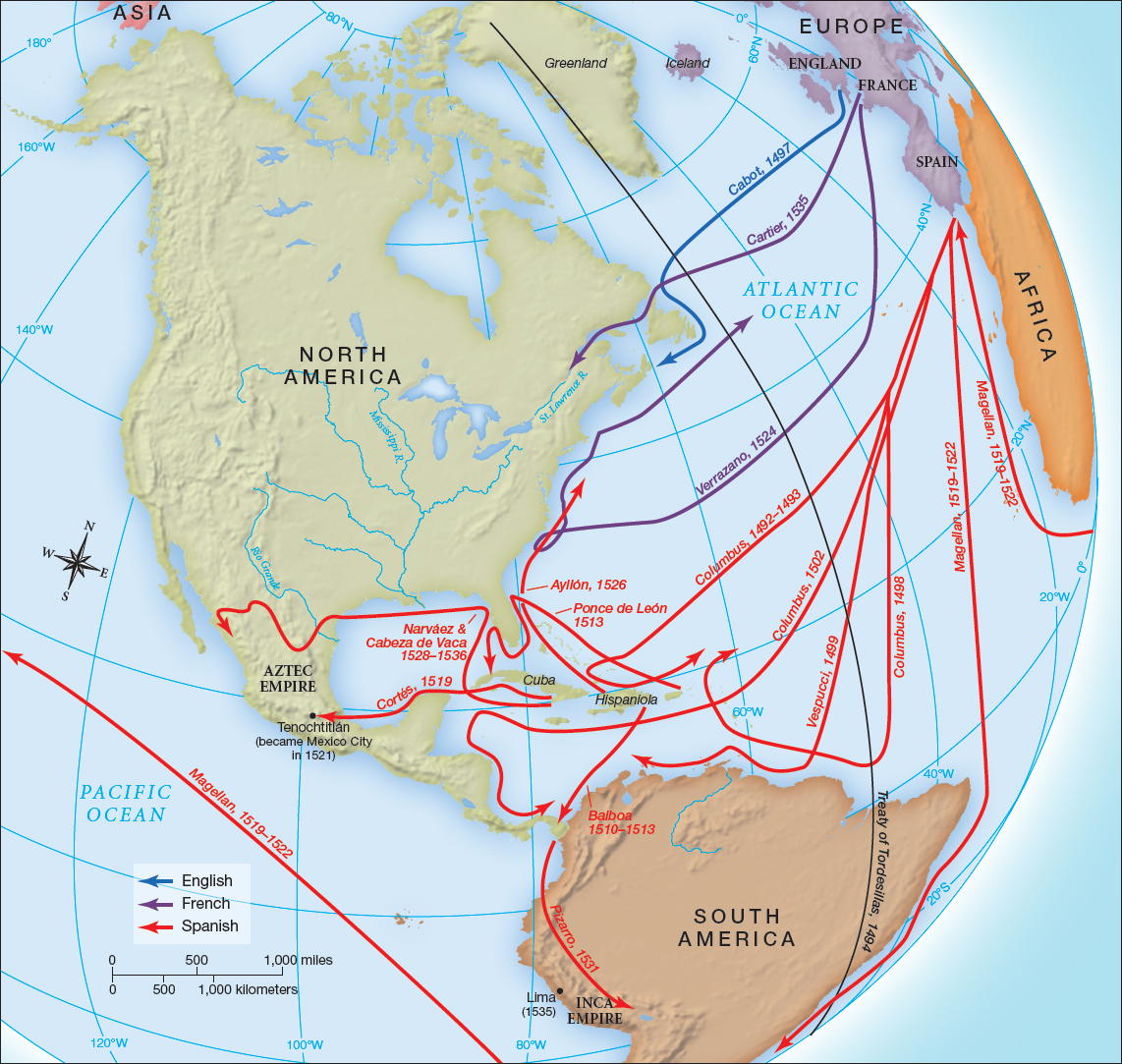

Nonetheless, Columbus’s voyages inspired others to head across the Atlantic (Map 1.3). In 1497 another Genoese navigator, John Cabot (or Caboto), sailing under the English flag, headed into the northern Atlantic in a tiny ship with only eighteen men. He reached an island off Cape Breton, where he discovered good cod fishing but met no local inhabitants. Over the next several years, Cabot and his son Sebastian made more trips to North American shores, but England failed to follow up on their discoveries.

More important at the time, Portuguese and Spanish mariners continued to explore the western edges of the Caribbean. Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine merchant, joined one such voyage in 1499. It was Vespucci’s account of his journey that led Martin Waldseemüller to identify the new continent he charted on his 1507 Universalis Cosmographia as “America.” Meanwhile, Spanish explorers subdued tribes like the Arawak and Taino in the Caribbean and headed toward the mainland. In 1513 Vasco Nuñez de Balboa traveled across the Isthmus of Darien (now Panama) and became the first European to see the Pacific Ocean. That same year, Juan Ponce de León launched a search for gold and slaves along a peninsula to the north. Although he did not find riches there, he named the region Florida, meaning “flowery land,” and claimed it for Spain.

Ferdinand Magellan launched an even more impressive expedition in August 1519 when he, with the support of Charles V of Spain, sought a passageway through South America to Asia. In the first fifteen months, Magellan faced bad weather, disappointments, hostile Indians, and open mutiny. But he managed to maintain his authority, and in October 1520 his crew discovered a strait at the southernmost tip of South America that connected the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Ill with scurvy and near starvation, the crew reached Guam and then the Philippines in March 1521. Magellan died there a month later, but one of his five ships and eighteen of the original crew finally made it back to Seville in September 1522, having successfully circumnavigated the globe. Despite the enormous loss of life and equipment, Magellan’s lone ship was loaded with valuable spices, his venture allowed Spain to claim the Philippine Islands, and his journals provided cartographers with vast amounts of knowledge about the world’s oceans and landmasses.