Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 18

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 17

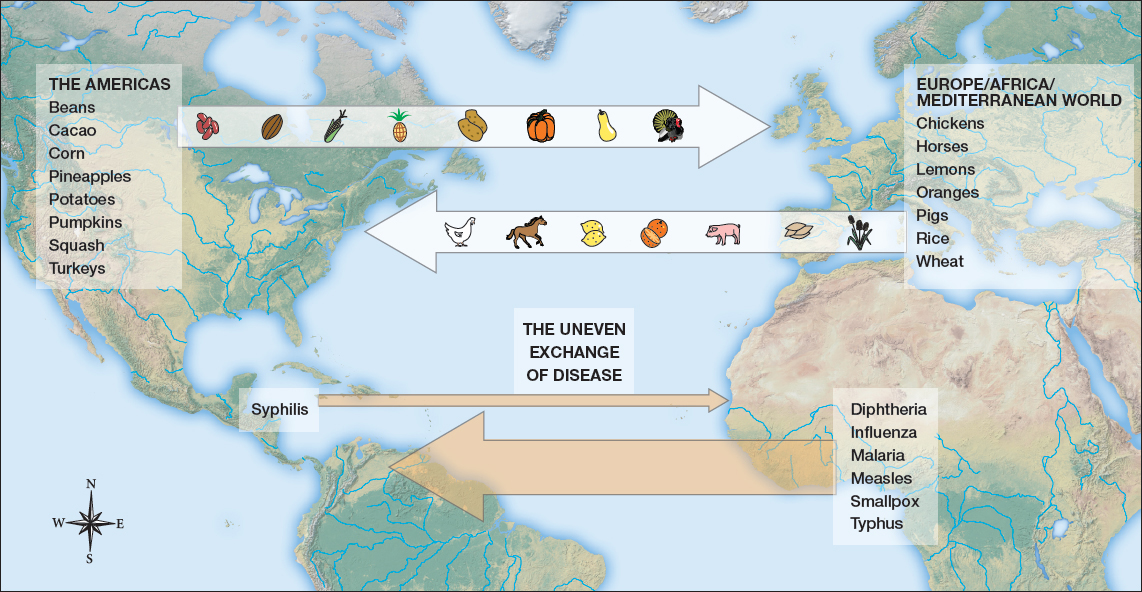

The Columbian Exchange

Even as maps documented Europeans’ expanded knowledge of the Americas, they could not capture the experience of contact between peoples separated for centuries by the Atlantic Ocean. Most important, the Spaniards were aided in their conquest of the Americas as much by germs as by maps, guns, or horses. Because native peoples in the Western Hemisphere had had almost no contact with the rest of the world for millennia, they lacked immunity to most germs carried by Europeans. Disease along with warfare first eradicated the Arawak and Taino on Hispaniola, wiping out some 300,000 people. In the Inca empire, the population plummeted from about 9 million in 1530 to less than half a million by 1630. Among the Aztecs, the Maya, and their neighbors, the population collapsed from some 40 million people around 1500 to about 3 million a century and a half later. The germs spread northward as well, leading to catastrophic epidemics among the Pueblo peoples of the Southwest and the Mississippian cultures of the Southeast.

These demographic disasters—far more devastating even than the bubonic plague in Europe—were part of what historians call the Columbian exchange. But this exchange also involved animals, plants, and seeds and affected Africa and Asia as well as Europe and the Americas. The transfer of flora and fauna and the spread of diseases transformed the economies and environments of all four continents. Initially, however, it was the catastrophic decline in Indian populations that ensured the victory of Spain and other European powers over American populations, facilitating their subsequent exploitation of American land, labor, and resources.

The diseases that swept across the Americas came from Africa as well as Europe. Indeed, it was Africans’ partial immunity to malaria and yellow fever that made them so attractive to European traders seeking laborers for Caribbean islands after the native population was decimated. African coconuts and bananas had already been introduced to Europe, while European traders had provided their African counterparts with iron and pigs. Asia also participated in the exchange, introducing Europe and Africa not only to the bubonic plague but also to sugar, rice, tea, and highly coveted spices.

America provided Europeans with high-yielding, nutrient-rich foods like maize and potatoes, as well as new indulgences like tobacco and cacao. The conquered Inca and Aztec empires also provided vast quantities of gold and silver, making Spain the treasure-house of Europe and ensuring its dominance on the continent for several decades. Sugar was first developed in the East Indies, but once it took root in the West Indies, it, too, became a source of enormous profits and, when mixed with cacao, created an addictive drink known as chocolate.

In exchange for products that America offered to Europe and Africa, these continents sent rice, wheat, rye, lemons, and oranges as well as horses, cattle, pigs, chickens, and honeybees to the Western Hemisphere (Map 1.4). The grain crops transformed the American landscape, particularly in North America, where wheat became a major food source. Cattle and pigs, meanwhile, changed native diets, while horses inspired new methods of farming, transportation, and warfare throughout the Americas.

The Columbian exchange benefited Europe far more than the Americas. Initially, it also benefited Africa, providing new crops with high yields and rich nutrients. Ultimately, however, the spread of sugar and rice to the West Indies and European cravings for tobacco and cacao increased the demand for labor, which could not be met by the declining population of Indians. This situation ensured the expansion of the African slave trade. The consequences of the Columbian exchange were thus monumental for the peoples of all three continents.

Review & Relate

What were the short-term consequences in both Europe and the Americas of Columbus’s voyages? |

How did the Columbian exchange transform both the Americas and Europe? |