Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 628

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 518

The Philippine War

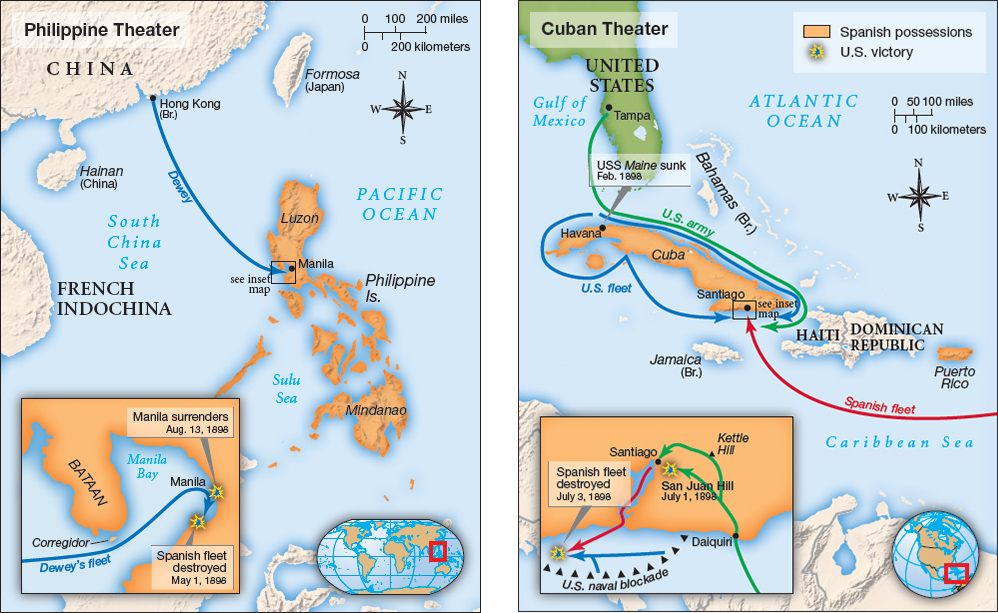

Even before invading Cuba, the United States had won a significant battle against Spain on the other side of the world. At the outset of the war, the U.S. Pacific Fleet, under the command of Commodore George Dewey, attacked Spanish forces in their colony of the Philippines. Dewey defeated the Spanish flotilla in Manila Bay on May 1, 1898, killing nearly four hundred Spanish sailors, while eight Americans suffered only minor injuries. Two and a half months later, American troops followed up with an invasion of Manila, and Spanish forces promptly surrendered (Map 20.1).

While pacifying Cuba, the U.S. government had to decide what to do with the Philippines. Imperialists viewed American control of the islands as an important step forward in the quest for entry into the China market. The Philippines could serve as a naval station for the merchant marine and the navy to safeguard potential trade with the Asian mainland. Moreover, President McKinley believed that if the United States did not act, another European power would take Spain’s place, something he thought would be “bad business and deplorable.”

With this in mind, McKinley decided to annex the Philippines. As with Cuba, McKinley and many other Americans believed that nonwhite Filipinos were not yet capable of self-government. Indiana senator Albert Beveridge commented: “We must never forget that in dealing with the Filipinos we deal with children.” McKinley agreed and set out “to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and Christianize them.” As was often the case with imperialism, assumptions of racial and cultural superiority provided a handy justification for the pursuit of economic and strategic advantage.

The president’s plans, however, ran into vigorous opposition. Anti-imperialist lawmakers took a strong stand against annexing the Philippines. Despite the jingoist fervor surrounding the War of 1898, opponents of imperialism constituted a vocal group. Their cause drew support from such prominent Americans as industrialist Andrew Carnegie, social reformer Jane Addams, writer Mark Twain, and labor organizer Samuel Gompers, all of whom joined the Anti-Imperialist League, founded in November 1898. Some argued that the United States would violate its anticolonialist heritage by acquiring the islands. Union leaders feared that annexation would prompt the migration of cheap laborers into the country and undercut wages. Others worried about the financial costs of supporting military forces across the Pacific. Most anti-imperialists had racial reasons for rejecting the treaty. Like imperialists, they considered Asians to be inferior to Europeans. In fact, many anti-imperialists held an even dimmer view of the capabilities of people of color than did their opponents, rejecting the notion that Filipinos could be “civilized” under American tutelage. See Document Project 20: Imperialism versus Anti-Imperialism.

Despite this opposition, the imperialists won out. Approval of the treaty annexing the Philippines in 1898 marked the beginning of problems for the United States. As in Cuba, rebellion had preceded American occupation. At first, the rebels welcomed the Americans as liberators, but once it became clear that American rule would simply replace Spanish rule, the mood changed. Led by Emilio Aguinaldo, insurgent forces fought back against the 70,000 troops sent by this latest colonial power. “Either independence or death!” became the battle cry of Aguinaldo’s rebel army. The rebels adopted guerrilla tactics and resorted to terrorist assaults against the U.S. army.

U.S. forces responded in kind, adopting harsh methods to suppress the uprising. General Jacob H. Smithy ordered his troops to “kill and burn, and the more you kill and burn, the better you will please me.” Racist sentiments inflamed passions against the dark-skinned Filipino insurgents. One American soldier wrote home saying that “he wanted to blow every nigger into nigger heaven.” American counterinsurgency efforts, which indiscriminately targeted combatants and civilians alike, alienated the native population. An estimated 200,000 Filipino civilians died between 1899 and 1902.

The Americans’ taste for war and sacrifice quickly waned. Nearly 5,000 Americans died in the Philippine war, far more combat deaths than in Cuba. With casualties mounting and reports growing of combat-related atrocities, antiwar sentiment spread in the United States. Dissenters turned imperialist arguments of manly American honor upside down. Reports of battlefield horrors inflicted on Filipino civilians prompted Senator George L. Wellington of Maryland to complain that the army had “step by step departed from the broad highway of honorable warfare . . . and [had] adopted methods of barbarism and savagery such as the wild natives of the unconquered Philippine Islands could not approach.” For many Americans, the “splendid little war” had turned into a sordid affair. Anti-imperialists claimed that the war had done nothing to affirm American manhood; rather, they charged, the United States acted as a bully, taking the position of “a strong man” fighting against “a weak and puny child.”

Despite growing casualties on the battlefield and antiwar sentiment at home, the conflict ended with an American military victory. In March 1901, U.S. forces captured Aguinaldo and broke the back of the rebellion. Exhausted, the Filipino leader asked his comrades to lay down their arms. In July 1901, President McKinley appointed Judge William Howard Taft of Ohio as the first civilian governor to oversee the government of the Philippines. For the next forty-five years, except for a brief period of Japanese rule during World War II, the United States remained in control of the islands.

Review & Relate

|

Why did the United States go to war with Spain in 1898? |

In what ways did the War of 1898 mark a turning point in the relationship between the United States and the rest of the world? |