Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 623

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 512

The Economics of Expansion

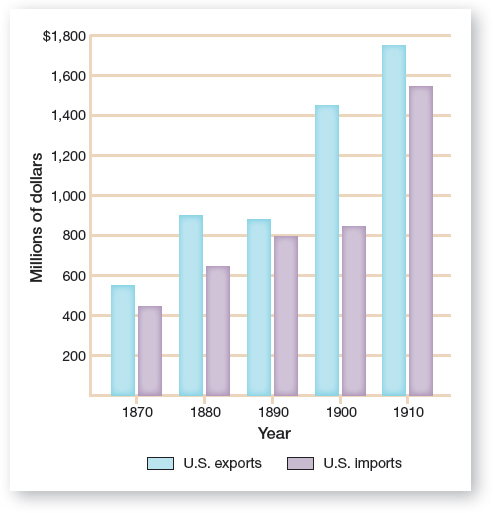

The industrialization of America and the growth of corporate capitalism stimulated imperialist desires in the late nineteenth century. Throughout its early history, the United States had sought overseas markets for exports, particularly its agricultural products. However, the importance of exports to the American economy increased dramatically in the second half of the nineteenth century, as industrialization gained momentum. In 1870 American exports totaled $500 million. By 1905 the value of American exports had increased sixfold to $1.5 billion Figure 20.1). John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company led the way in selling products to European and Asian markets, and firms such as Coca-Cola, Kodak, and McCormick earned profits by exporting soft drinks, cameras, and farm machinery, respectively.

The bulk of American exports went to the developed markets of Europe and Canada, which had the greatest purchasing power. Although the less economically advanced nations of Latin America and Asia did not have the same ability to buy American products, businessmen still considered these regions—especially China, with a population of millions of potential consumers—as future markets for American industries.

The desire to expand foreign markets remained a steady feature of American business interests. The fear that the domestic market for manufactured goods was shrinking gave this expansionist hunger greater urgency. The fluctuating business cycle of boom and bust that characterized the economy in the 1870s and 1880s reached its peak in the depression of the 1890s, the most severe economic downturn up to that point in American history. The social unrest that accompanied this depression, including protest marches and strikes (see chapter 17), worried business and political leaders about the stability of the country. The way to sustain prosperity and contain radicalism, many businessmen agreed, was to find foreign markets for goods that poured out of factories but could not be absorbed at home. Senator William Frye of Maine argued, “We must have the market [of China] or we shall have revolution.”

Similar commercial ambitions led many Americans to see Hawaii as an imperial prize. Interest in the islands dated back to the early nineteenth century. American missionaries first visited the Hawaiian Islands in 1820. As missionaries tried to convert native islanders to Christianity, American businessmen sought to establish plantations on the islands, especially to grow sugarcane, as the market for sugar had grown rapidly during the 1870s and 1880s. In exchange for duty-free access to the U.S. sugar market, white Hawaiians signed an agreement in 1887 that granted the United States exclusive rights to a naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu.

The growing influence of white sugar planters on the islands alarmed native Hawaiians. In 1891 Queen Liliuokalani, a strong nationalist leader who voiced the slogan “Hawaii for the Hawaiians,” sought to increase the power of the indigenous peoples she governed, at the expense of the sugar growers. In 1893 white plantation owners, with the cooperation of the American ambassador to Hawaii and 150 U.S. marines, overthrew the queen’s government. Once in command of the government, they entered into a treaty of annexation with the United States. However, President Grover Cleveland opposed annexation and withdrew the treaty. Nevertheless, planters remained in power and waited for a suitable opportunity to seek annexation.