Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 659

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 544

Americans Become Consumers

The 1920s marked a period of economic expansion and general prosperity. National income rose from approximately $63 billion to $88 billion and per capita income jumped from $641 to $847, an increase of 32 percent. The purchasing power of wage earners climbed approximately 20 percent.

This great spurt of economic growth in the 1920s resulted from the application of technological innovation and scientific management techniques to industrial production (Figure 21.1). Perhaps the greatest innovation came with the introduction of the assembly line. First used in the automobile industry before World War I, the assembly line moved the product to a worker who performed a specific task before sending it along to the next worker. This deceptively simple system, perfected by Henry Ford, saved enormous time and energy by emphasizing repetition, accuracy, and standardization. As a result, a new car rolled out of one of Ford’s auto plants in less than a minute—earlier it had taken twelve and a half hours. Streamlined production lowered costs, which, in turn, allowed Ford to lower prices. The price of a new Model T dropped from $725 in 1910 to $290 in the early 1920s.

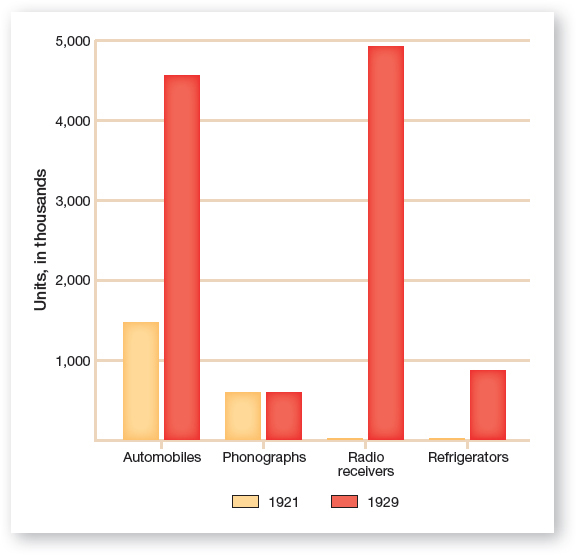

Besides the automobile, the second industrial revolution focused on the production of consumer-oriented goods previously considered luxuries. The electrification of urban homes created demand for a wealth of new laborsaving appliances; rural areas, most of which lacked electricity, did not benefit. Refrigerators, washing machines, toasters, and vacuum cleaners appealed to middle-class housewives whose husbands could afford to purchase them. Wristwatches replaced bulkier pocket watches. Radios became the chief source of home entertainment, and families gathered around the radio console to listen to music, news, and sports. Religious and political radio programs helped spread their particular faiths and ideologies, and those farmers equipped with electricity depended on the radio for weather reports and agricultural prices.

Although such household items changed the lives of many Americans, no single product had as profound an effect on American life in the 1920s as the automobile. Auto sales soared in the 1920s from 1.5 million to 5 million, making Henry Ford a multimillionaire and fueling the growth of related industries such as steel, rubber, petroleum, and glass. In 1929 Ford and his competitors at General Motors, Chevrolet, and Oldsmobile employed nearly 4 million workers, and around one in eight American workers toiled in factories connected to automobile production.

The automobile also changed day-to-day living patterns. Although most roads and highways consisted of dirt and contained rocks and ruts, enough were paved to extend the boundaries of suburbs farther from the city. By the end of the 1920s, around 17 percent of Americans lived in suburbia. Cars allowed families to travel to vacation destinations at greater distances from their homes. Even the roadside landscape changed to accommodate weary travelers, as gas stations, diners, and motels sprang up to serve them, and advertisers constructed billboards along the roads to remind them of what they needed. Each year, vacation resorts on the east and west coasts of Florida attracted thousands of tourists who drove south to enjoy the state’s balmy climate and beautiful beaches. The use of automobile technology blended the conveniences of modern America with the primitiveness of the environment. Outdoor camping became the craze.

The automobile also provided new dating opportunities for young men and women. At the turn of the twentieth century, a young man courted a woman by going to her home and sitting with her on the sofa or out on the porch under the watchful eyes of her parents and family members. When the couple left the house, they might walk to a park and listen to a bandstand concert, again in the company of others. With the arrival of the automobile, couples could move from the couch in the parlor to the backseat of a car, away from adult supervision. Driving to a “lover’s lane” in a Model T and drinking from a flask of prohibited alcohol, the young couple could explore new sexual terrain that had been denied them in the past (most likely “petting”—kissing and rubbing rather than intercourse).

Although Ford and his fellow manufacturers had succeeded in lowering prices for consumers, they still had to convince Americans to spend their hard-earned money to purchase their products. Turning for help to New York City’s Madison Avenue, the location of the fledgling advertising industry, manufacturers nearly tripled their spending on advertising over the course of the 1920s. Firms pitched their products around price and quality, but they directed their efforts more than ever to the personal psychology of the consumer. Advertisers played on consumers’ unexpressed fears, unfulfilled desires, hopes for success, and sexual fantasies. The producers of Listerine mouthwash transformed a product previously used to disinfect hospitals into one that fought the dreaded but made-up disease of halitosis (bad breath). Advertisers told people that they could measure success through consumption. Purchasing a General Electric (GE) all-steel refrigerator not only would preserve food longer but also would enhance the owners’ reputation among their neighbors. “Happy to own it . . . proud to show it” headlined one ad explaining the virtues of GE’s new product.

Explore

See Document 21.1 for a typical GE advertisement from 1928.

Although average wages and incomes rose during the 1920s, the majority of Americans did not have the disposable income to afford the bounty of new consumer goods. To resolve this problem, companies extended credit in dizzying amounts. By 1929 consumers purchased 60 percent of their cars and 80 percent of their radios and furniture on credit in the form of installment plans and owed a total of $3 billion. “Buy now and pay later” became the motto of corporate America. By putting a small amount down and making monthly payments with interest, people could obtain an assortment of consumer items they otherwise could not afford.