Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 689

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 566

Hoover Faces the Depression

National prosperity was at its peak when the Republican Hoover entered the White House in March 1929. The nation had little reason to doubt him when he boasted in his inaugural address: “We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land. The poorhouse is vanishing from among us.” These words were still ringing in the public’s ears when the stock market crashed later that year.

Hoover brought to the presidency a blend of traditional and progressive ideas. He believed that government and business should form voluntary partnerships to work toward common goals. Rejecting the principle of absolute laissez-faire, he nonetheless argued that the government should extend its influence lightly over the economy—to encourage and persuade sensible behavior, but not to impose itself on the private sector.

The Great Depression sorely tested Hoover’s beliefs. Having placed his faith in cooperation rather than coercion, the president relied on voluntarism to get the nation through hard economic times. Hoover hoped that management and labor, through gentle persuasion, would hold steady on prices and wages and calmly wait until the worst of the depression passed. In the meantime, for those in dire need, the president turned to local communities and private charities. Hoover expected municipal and state governments to shoulder the burden of providing relief to the needy, just as they had during previous economic downturns.

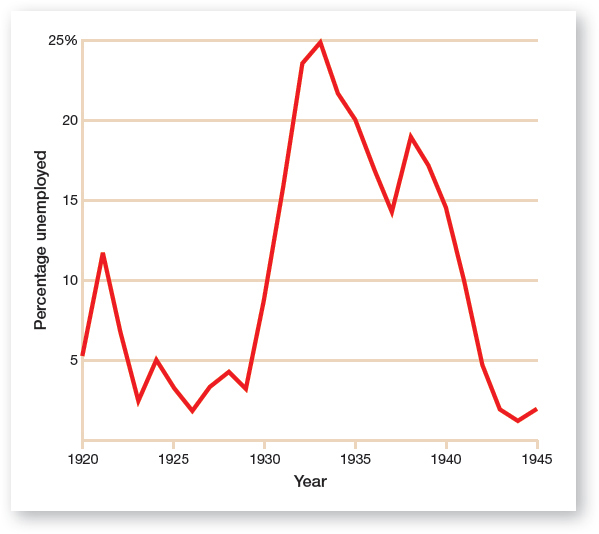

Hoover’s remedies failed to rally the country back to good economic health. Initially, business people responded positively to the president’s request to maintain the status quo, but when the economy did not bounce back, they lost confidence and defected. Nor did local governments and private agencies have the funds to provide relief to all those who needed it. With tax revenues in decline, some 1,300 municipalities across the country had gone bankrupt by 1933. Chicago and other cities stopped paying their teachers. Benevolent societies and religious groups could handle short-term misfortunes, but they could not cope with the ongoing disaster of mass unemployment (Figure 22.1).

As confidence in recovery fell and the economy sank deeper into depression, President Hoover shifted direction. Without abandoning his belief in voluntarism, the president persuaded Congress to lower income tax rates and to allocate an unprecedented $423 million for federal public works projects. In 1929 the president signed into law the Agricultural Marketing Act, a measure aimed at raising prices for long-suffering farmers.

In general, Hoover had the right idea, but he retreated from initiating greater spending because he feared government deficits more than unemployment. With federal accounting sheets showing a rising deficit, Hoover reversed course in 1932 and joined with Congress in sharply raising income, estate, and corporate taxes on the wealthy. This effectively slowed down investment and new production, throwing millions more American workers out of jobs. The Hawley-Smoot Act passed by Congress in 1930 made matters worse. In an effort to replenish revenues and protect American farmers and companies from foreign competition, the act increased tariffs on agricultural and industrial imports. However, other countries retaliated by lifting their import duties, which hurt American companies because it diminished demand for American exports.

In an exception to his aversion to spending, Hoover lobbied Congress to create the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to supply loans to banks in danger of collapsing, financially strapped railroads, and troubled insurance companies. By injecting federal dollars into these critical enterprises, the president and lawmakers expected to produce dividends that would trickle down from the top of the economic structure to the bottom. Renewed investment supposedly would increase production, create jobs, raise the income of workers, and generate consumption and economic recovery. In 1932 Congress gave the RFC a budget of $1.5 billion to employ people in public works projects, a significant allocation for those individuals hardest hit by the depression.

This notable departure from Republican economic philosophy fell short of its goal. The RFC spent its budget too cautiously, and its funds reached primarily those institutions that could best afford to repay the loans, ignoring the companies in the greatest difficulty. Whatever the president’s intentions, wealth never trickled down. Hoover was not indifferent to the plight of others so much as he was incapable of breaking away from his ideological preconceptions. He refused to support expenditures for direct relief (what today we call welfare) and hesitated to extend assistance for work relief because he believed that it would ruin individual initiative and character.

Hoover and the United States did not face the Great Depression alone; it was a worldwide calamity. By 1933 Germany, France, and Great Britain all faced mass unemployment. In Britain, one survey showed that around 20 percent of the population lacked sufficient food, clothing, and housing. As with American agriculture, European farmers had been suffering since the 1920s from falling prices and increased debt, and the depression further exacerbated this problem. In this climate of extreme social and economic unrest, authoritarian dictators came to power in a number of European countries, including Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Each claimed that his country’s social and economic problems could be solved only by placing power in the hands of a single, all-powerful leader.