Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 690

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 568

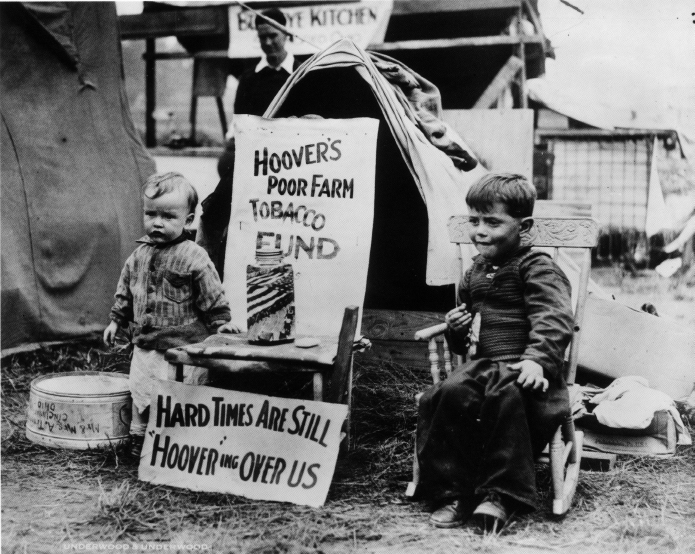

Hoovervilles and Dust Storms

The depression hit all areas of the United States hard. In large cities, families crowded into apartments with no gas or electricity and little food to put on the table. In Los Angeles, people cooked their meals over wood fires in backyards. An observer in Philadelphia reported a house containing a family of eleven. “They’ve got no shoes, no pants,” he lamented. “In the house, no chairs. My God, you go in there, you cry, that’s all.” In many cities, the homeless constructed makeshift housing consisting of cartons, old newspapers, and cloth—shanties that journalists derisively dubbed Hoovervilles. Thousands of hungry citizens wound up living under bridges in Portland, Oregon; in wrecked autos in city dumps in Brooklyn, New York, and Stockton, California; and in abandoned coal furnaces in Pittsburgh. In Chicago, a fight broke out among fifty men over scraps of food placed in the garbage outside of a restaurant.

Rural workers fared no better. Landlords in West Virginia and Kentucky evicted coal miners and their families from their homes in the dead of winter, forcing them to live in tents. Farmers in the Great Plains, who were already experiencing foreclosures, were little prepared for the even greater natural disaster that lay waste to their farms. In the early 1930s, dust storms swept through western Kansas, eastern Colorado, western Oklahoma, the Texas Panhandle, and eastern New Mexico, destroying crops and plant and animal life. The storms resulted from both climatological and human causes. A series of droughts had destroyed crops and turned the earth into sand, which gusts of wind deposited on everything that lay in their path. Though they did not realize it at the time, plains farmers, by focusing on growing wheat for income, had neglected planting trees and grasses that would have kept the earth from eroding and turning into dust. Instead, dust storms brought life to a grinding halt, blocking out the midday sun. See Document Project 22: The Depression in Rural America.

As the storms continued through the 1930s, most residents—approximately 75 percent—remained on the plains and rode out the blizzards of dust. Millions, however, headed for California by train, automobiles, and trucks looking for relief from the plague of swirling dirt and hoping to find jobs in the state’s fruit and vegetable fields. Although they came from several states besides Oklahoma, these migrants came to be known as “Okies,” a derogatory term used by those who resented and looked down on the poverty-stricken newcomers to their communities. John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939) portrayed the plight of the fictional Joad family, as storms and a bank foreclosure destroyed their Oklahoma farm and sent them on the road to California. “[Route] 66 is the path of a people in flight,” Steinbeck wrote, “refugees from dust and shrinking land, from the thunder of tractors and shrinking ownership, from the desert’s slow northward invasion, from the twisting winds that howl up out of Texas, from the floods that bring no richness to the land and steal what little richness is there.” By no means did all the migrants suffer the misfortunes of the Joads, and many of them succeeded in establishing new lives in the West.