Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 732

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 603

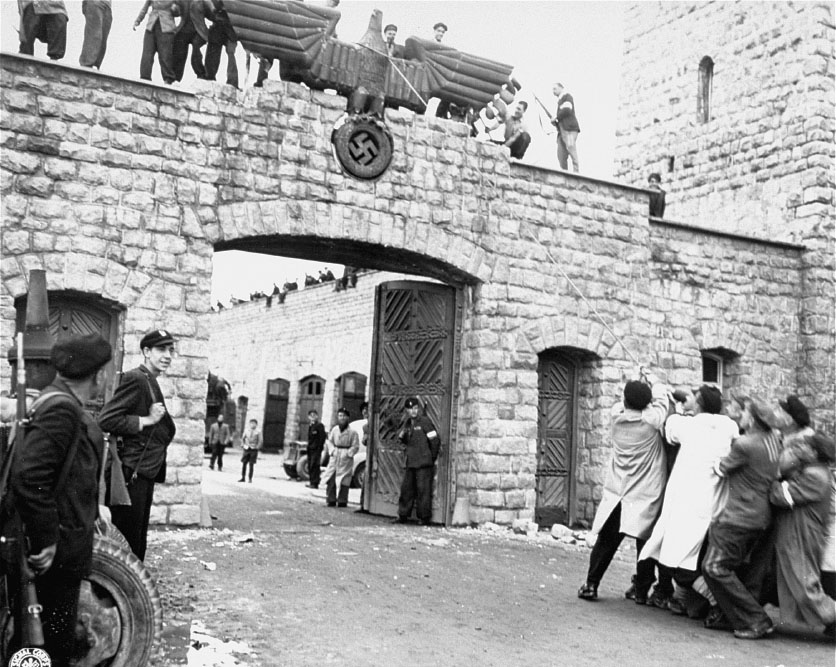

Evidence of the Holocaust

The end of the war revealed the full extent and horror of Germany’s calculated and methodical slaughter of certain religious, ethnic, and political groups. As Allied troops liberated Germany and Poland, they saw for themselves the brutality of the Nazi concentration camps that Hitler had set up to execute or work to death 6 million Jews and another 5 million “undesirables”—Slavs, Poles, Gypsies, homosexuals, the physically and mentally disabled, and Communists. At Buchenwald and Dachau in Germany and at Auschwitz in Poland, the Allies encountered the skeletal remains of inmates tossed into mass graves, dead from starvation, illness, and executions. Crematoria on the premises contained the ashes of inmates first poisoned and then incinerated. Troops also freed the “living dead,” those still alive but seriously ill and undernourished. One U.S. soldier reported his initial impression of the inmates: “They were . . . all skin and bones. They were sick, starving, and dying.”

These horrific discoveries shocked the public, but evidence of what was happening had appeared early in the war. Journalists like Varian Fry had outlined the Nazi atrocities against the Jews several years before. “Letters, reports, tables all fit together. They add up to the most appalling picture of mass murder in all human history,” Fry wrote in the New Republic magazine in 1942. He called on Roosevelt and Churchill to speak out forcefully, urged the pope to excommunicate Catholics who participated in Nazi crimes, and proposed sending food to occupied countries to counter the Nazi claim that they were killing Jews and Poles because there was not enough food to go around.

The Roosevelt administration did little in response, despite receiving evidence of the Nazi death camps beginning in 1942. It chose not to send planes to bomb the concentration camps or the railroad lines leading to them, deeming it too risky militarily and too dangerous for the inmates. In a less defensible decision, the Roosevelt administration refused to relax immigration laws to allow Jews and other persecuted minorities to take refuge in the United States, and only 21,000 managed to find asylum. The State Department, which could have modified these policies, was staffed with anti-Semitic officials, and though President Roosevelt expressed sympathy for the plight of Hitler’s victims, he believed that winning the war as quickly as possible was the best way to help them.

Review & Relate

|

How did the Allies win the war in Europe and in the Pacific? |

How did tensions among the Allies shape both their military strategy and their postwar plans? |