Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 734

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 604

Managing the Wartime Economy

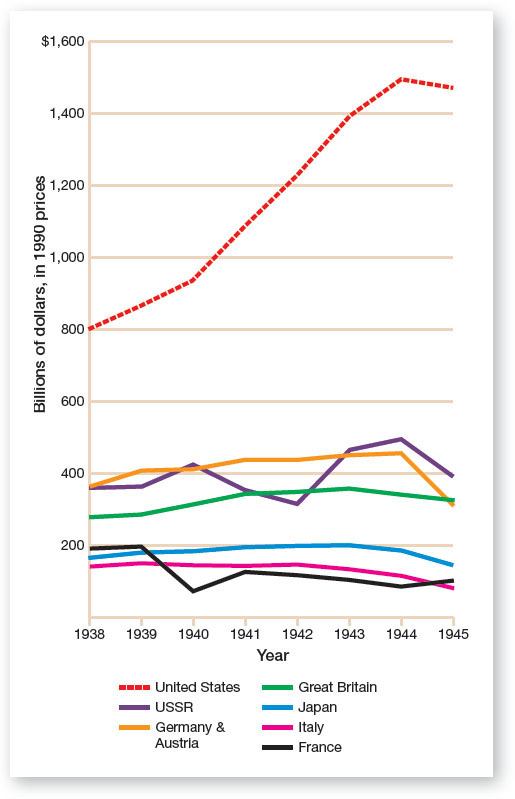

To mobilize for war, President Roosevelt increased federal spending to unprecedented levels. Federal government employment during the war expanded to an all-time high of 3.8 million workers, four times as many as during the New Deal, setting the foundation for a large, permanent Washington bureaucracy. War orders fueled economic growth, productivity, and employment. In 1939 the federal budget stood at $9 billion; by the end of the war, it had grown to more than $100 billion. The gross national product increased from $91 billion to $166 billion during the war (Figure 23.1), union membership rose from around 9 million to nearly 15 million, and unemployment dropped from 8 million to less than 1 million. The armed forces helped reduce unemployment significantly by enlisting 12 million men and women, 7 million of whom had been unemployed. Workers earned extra income for overtime work, but because of the rationing of consumer goods, Americans had to defer personal spending.

Prosperity was not limited to any one region. The industrial areas of the Northeast and Midwest once again boomed, as automobile factories converted to building tanks and other military vehicles, oil refineries processed gasoline to fuel them, steel and rubber companies manufactured parts to construct these vehicles and the weapons they carried, and textile and shoe plants furnished uniforms and boots for soldiers to wear. As farmers provided food for the nation and its allies, the index of farm production (which was 100 in 1939) jumped from 108 in 1940 to 126 in 1946. The economy diversified geographically. Fifteen million Americans—11 percent of the entire population—migrated between 1941 and 1945, and another 12 million left their homes and joined the armed forces. The war transformed the agricultural South into a budding industrial region. The federal government poured more than $4 billion in contracts into the South to operate military camps, contract with textile factories to clothe the military, and use its ports to build and launch warships. The availability of jobs in southern cities attracted sharecroppers and tenant farmers, black and white, away from the countryside and promoted urbanization while reducing the region’s dependency on the plantation economy. In similar fashion, the West Coast prospered because it was the gateway to the Pacific war. The federal government established aircraft plants and shipbuilding yards in California, Oregon, and Washington, resulting in extraordinary population growth in Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle. Black and white migrants from Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana headed west to take advantage of these opportunities.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Congress passed the War Powers Act, which authorized the president to reorganize federal agencies any way he thought necessary to win the war. Roosevelt replaced the agencies he had created to combat the Great Depression with another outpouring of organizations to fight the Axis powers. In 1942 the president established the War Production Board to oversee the economy. The agency enticed business corporations to meet ever-increasing government orders by negotiating lucrative contracts that helped underwrite their costs, lower their taxes, and guarantee large profits. During the course of the war, corporate net profits nearly doubled. The government also suspended antitrust enforcement, giving private companies great leeway in running their enterprises. Much of the antibusiness hostility generated by the Great Depression evaporated as the Roosevelt administration recruited business executives to supervise government agencies for the token pay of $1 a year. Indeed, the close relationship between the federal government and business that emerged during the war produced the military-industrial complex—the government-business alliance that would have a vast influence on the future development of the economy.

In the first three years of the war, the United States increased military production by some 800 percent. American factories accounted for more than half of worldwide manufacturing output. On their best days, U.S. plants built a ship a day and an airplane every five minutes. By 1945 the United States had produced 86,000 tanks, nearly 300,000 airplanes, 15 million rifles and machine guns, and 6,500 ships.

Financing this enormous enterprise took considerable effort. The federal government spent more than $320 billion, ten times the cost of World War I. To pay for the war, the federal government sold $100 billion in bonds, only about half of what was needed. The rest came from increased income tax rates, which for the first time affected low- and middle-income workers who had paid little or no tax before. At the same time, the tax rate for the wealthy was boosted to 94 percent. In addition to paying higher taxes, American consumers shouldered the burden of inflation. Shortages in household and personal goods produced higher prices, which meant lower purchasing power. During the war, consumer prices jumped by 28 percent, despite the efforts of another federal agency, the Office of Price Administration, to stabilize them.

Building up the armed forces was the final ingredient in the mobilization for war. In 1940 about 250,000 soldiers were serving in the U.S. military, compared with Germany’s 6 to 8 million troops. By 1945 American forces had grown to more than 12 million men and women through voluntary enlistments and a draft of men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five. The military reflected the diversity of the U.S. population. The sons of immigrants fought alongside the sons of older-stock Americans. Although the military tried to exclude homosexuals, they managed to join the fighting forces. Some 700,000 African Americans served in the armed forces, but civilian and military officials confined them to segregated units in the army, assigned them to menial work in the navy, and excluded them from the U.S. Marine Corps. The Army Air Corps created a segregated fighting unit trained at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, and these Tuskegee airmen, like their counterparts among the ground forces, distinguished themselves in battle. Women could not fight in combat, but 140,000 joined the Women’s Army Corps, and 100,000 joined the navy’s WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service). In these and other service branches, women contributed mainly as nurses and performed transportation and clerical duties.

The concentration of power in the executive branch that accompanied the war effort, together with the president’s expanded role in international diplomacy, fostered what historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. termed “the imperial presidency.” As commanders in chief, Roosevelt and his successors waged war and negotiated peace by controlling and manipulating the flow of information that reached Congress and the American public. Together with the burgeoning military-industrial complex, the imperial presidency redistributed power both within Washington and throughout the country at large.

The government relied on corporate executives to manage wartime economic conversion, but without the sacrifice and dedication of American workers, their efforts would have failed. The demands for wartime production combined with the departure of millions of American workers to the military created a labor shortage that gave unions increased leverage. By 1945 the membership rolls of organized labor had grown from 9 million to nearly 14 million. In 1942 the Roosevelt administration established the National War Labor Board, which regulated wages, hours, and working conditions and authorized the government to take over plants that refused to abide by its decisions. Unions at first refrained from striking but later in the war organized strikes to protest the disparity between workers’ wages and corporate profits. In 1943 Congress responded by passing the Smith-Connally Act, which prohibited walkouts in defense industries and set a thirty-day “cooling-off” period before unions could go out on strike.