Exploring American Histories: Printed Page 721

Exploring American Histories, Value Edition: Printed Page 591

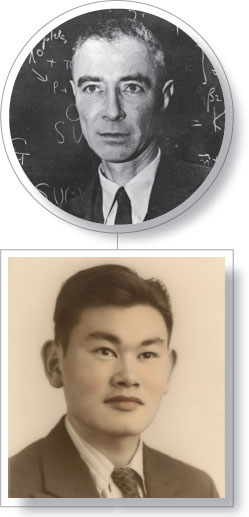

American Histories: J. Robert Oppenheimer and Fred Korematsu

AMERICAN HISTORIES

One month after Japan attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the United States entered World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt approved a full-scale effort to develop an atomic bomb. As scientific director of this top-secret program, called the Manhattan Engineering District Project, physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer orchestrated the work of more than 3,000 scientists, technicians, and military personnel at the Los Alamos Laboratories near Santa Fe, New Mexico. The thirty-seven-year-old Oppenheimer, the son of German American Jews, had studied theoretical physics in England and Germany and then returned to the United States to teach physics. He was also interested and engaged in world events. When the Nazis began persecuting German Jews in the early 1930s, Oppenheimer helped Jews gain asylum in the United States.

On July 16, 1945, Oppenheimer and his team successfully tested their new weapon. The explosion, which had a force equal to more than 18,000 tons of TNT, lit up the predawn sky with a blast so powerful that it broke a window 125 miles away and so bright that a blind woman claimed she saw a flash of light. A mushroom cloud shot up 41,000 feet into the sky over ground zero, where a 1,200-foot-wide crater had formed. Oppenheimer understood that the world had been permanently transformed. Quoting from Hindu scriptures, he remembered thinking at the moment of the explosion, “I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

On August 6, 1945, Army Air Corps planes dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima and three days later another one on Nagasaki, resulting in the deaths of more than 200,000 civilians. Profoundly shaken by the death and destruction his efforts had produced, Oppenheimer observed: “If atomic bombs are to be added to the arsenals of a warring world, or to the arsenals of nations preparing for war, then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima.”

While Oppenheimer and his team remained cloistered at Los Alamos, Fred Korematsu and some 112,000 Japanese Americans lived in internment camps, imprisoned for no other reason than their Japanese ancestry. Born in Oakland, California, in 1919 to Japanese immigrants, Fred and his three brothers grew up like many first-generation Americans. Fred’s parents spoke Japanese at home and maintained the cultural traditions of their native land, while their sons learned English in public school, ate hamburgers, and played football and basketball like other children their age. After graduating from high school in 1938, Korematsu worked on the Oakland docks as a welder.

After the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, residents on the West Coast turned their anger on the Japanese and Japanese Americans living among them. As assimilated as Fred Korematsu and many other Nisei (the U.S.-born children of Japanese immigrants) had become, white Americans doubted their loyalty and viewed them as a threat to national security. Korematsu could no longer get a haircut in a white-owned barbershop; the Boilermakers Union expelled him, and he lost his job as a welder; and he was not allowed to join the U.S. coast guard because of his race.

These indignities foreshadowed events to come. On March 21, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 authorizing military commanders on the West Coast to take any measures necessary to promote national security. Consequently, officials imposed a curfew on Japanese Americans, excluded them from designated areas, and prohibited them from traveling more than twenty-five miles from their homes. On May 9, the military ordered Korematsu’s family to report to Tanforan Racetrack in San Mateo, from which they would be transported to internment camps throughout the West. Although the rest of his family complied with the order, Fred refused. He adopted the name “Clyde Sarah” and claimed to be of Spanish-Hawaiian ancestry. However, Korematsu’s efforts to resist internment failed. Three weeks later, he was arrested and later transferred to the Topaz internment camp in south-central Utah. Found guilty of violating the original evacuation order, Korematsu received a sentence of five years of probation. When he appealed his conviction to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1944, the high court upheld the verdict. By the time the first atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima, the government had closed down the internment camp where Fred Korematsu lived, and he had regained his freedom. •

THE AMERICAN HISTORIES of both Fred Korematsu and J. Robert Oppenheimer were shaped by the profound changes brought about by war. Korematsu was subjected to the full force of anti-Japanese sentiment that followed the attack on Pearl Harbor, while Oppenheimer played a key role in developing a weapon that he feared would lead to the destruction of mankind. Both men experienced a mixture of hope and uneasiness as they looked ahead to the postwar world.

The war that these two men experienced in such different ways marked a critical point for the United States in the twentieth century. World War II finally ended the Great Depression, cementing the trend toward government intervention in the economy that had begun with the New Deal. With the war fought almost entirely on foreign soil, the United States converted its factories to wartime production and became the “arsenal of democracy,” putting millions of Americans to work in the process, including African Americans, other minorities, and women. All Americans contributed to the war effort, whether they wanted to or not, through rationing and higher taxes. Overseas, soldiers fought fierce battles in Europe, Africa, and Asia. The combined military power of the Allies, led by the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, finally defeated the Axis nations of Germany, Italy, and Japan, but not until the fighting had killed 60 to 70 million people, more than half of whom were civilians, and ushered in the Atomic Age.